Conference season continued for our project with “Deciphering the Uncertain”, a two-day conference hosted by The University of Oxford China Centre. Organised by two Doctor of Philosophy Candidates at the University of Oxford, Flaminia Pischedda (Oriental Studies (Chinese)) and Domenico Giordani (Classics), the conference aimed to present a comprehensive, comparative appraisal of the structural features underpinning the universal human concern of uncertainty in “Early Text Cultures”. Ambitious in scope and execution, the conference featured panels on Mesopotamia, Greece, Rome, Ancient Egypt, Ancient Israel, Pre-Islamic Arabia, China, Japan, India, Central Europe, and Eastern Europe and Russia. The practices that were compared and contrasted across all these regions were those typically called “divinatory”.

Divination was broadly understood as practices which aimed to uncover the hidden significance of events and signs, whether naturally occurring or deliberately obtained, as well as those which aimed to interact with the divine in order to acquire foreknowledge. From divination manuals and handbooks for interpreting omina, to oracular procedures and astrological forecasts, the scope was wide, and the insights were fascinating. In particular, this is because the conference organisers conceived of a framework of five questions that could be used to draw out the principal features of these practices for comparison.

- How is divination defined and conceptualised in each society?

- What are the sources and texts through which we can reconstruct how divination worked? How do different material supports affect the way divination is performed?

- Who were the practitioners? Were they professionals or amateurs? Did they have connection with a temple or a court or were they independent? What was their cultural background?

- What were the techniques employed by these practitioners in interpreting divinatory signs, either natural or deliberately created?

- Are there any typological similarities in a set of practices which represent a shared feature among most ancient societies? If that be the case, is it possible to bring out distinctive aspects peculiar to each society within the complexity of the mantic art?

Far from being able to address let alone answer all these questions for each regional context over the course of the two days, this framework will form the basis of a volume to be produced in collaboration between the speakers in the coming years. This volume will aim to present to its readers the systems of knowledge behind these practices in all the different regions under study. Inspired by L. A. Raphals’ Divination and Prediction in Early China and Ancient Greece – a comparative study of divination techniques in both cultures – the volume proceeding from this conference aims to set the stage for future endeavours into cross-cultural comparisons and studies. In the meantime, each speaker gave insights into their own fascinating research, and the rest of this blogpost will concern the different panels that discussed divination in their particular regions of study.

Nicla de Zorzi (Vienna) discussed the analogical thinking behind omen texts in Ancient Mesopotamia. Through repetition with variation, the combination of positive observations leading to positive predictions and negative observations leading to negative predictions, de Zorzi analysed how Babylonian diviners could understand their world through analogical reasoning between the phenomena they observed, e.g. right is good and left is bad, and the implications these had for their futures.

Robert Parker (Oxford) surveyed numerous sources for “Greek Divination”, with an emphasis on the recently-excavated corpus of texts from the Oracle at Dodona, which increased the total number of oracular texts known from Greece from less than 200 to more than 4,000! Emphasising that the oracular questions themselves were always specific questions which would elicit a yes or no – binary – answer, Parker brought in comparisons with studies on systems of divination from Africa, such as the work by W.E.A. van Beek and P. M. Peek.

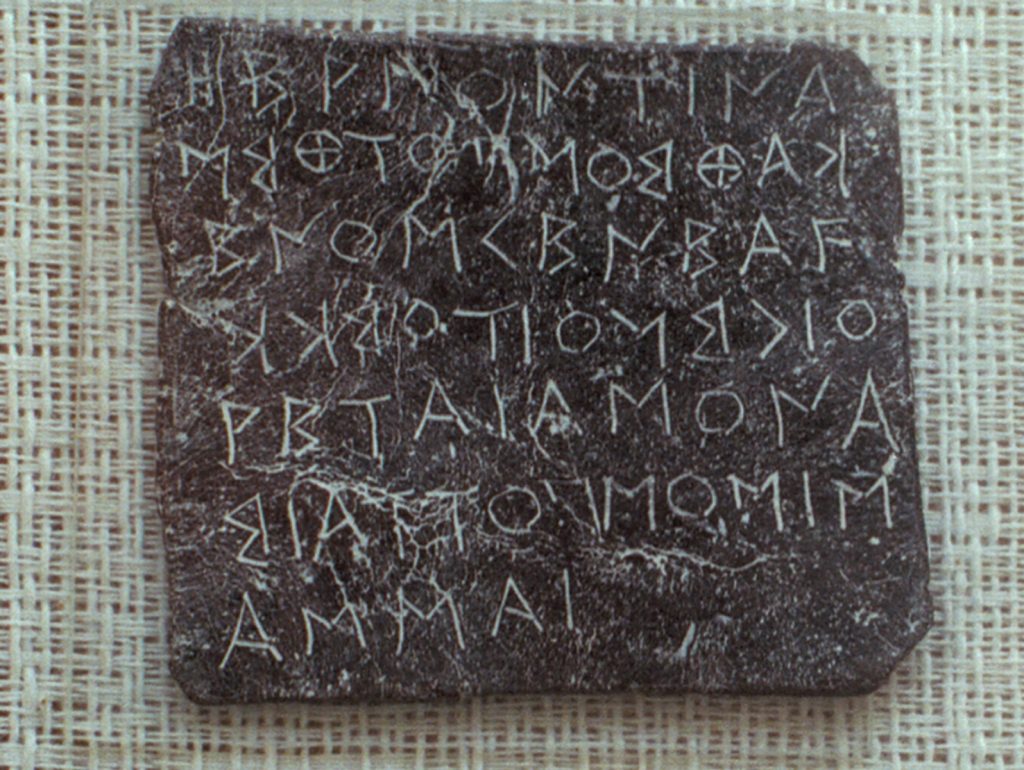

Ianannini Archaeological Museum M 12, 2941.

Federico Santangelo (Newcastle) surveyed “Text and Practice in Roman Divination” by first considering what classical authors had to say on the variety of practices they were aware of, and secondly the textual sources for divination themselves. How sparse the evidence is in primary sources for diviners themselves was highlighted, as was the fact that the principal evidence for divinatory practices comes from literary sources – such as Cicero’s On Divination. Santangelo also pointed out that divination as a practice was not only a private matter in Rome, but also one at times central to the running of the Roman polity itself.

Moving to Ancient Egypt, three speakers highlighted the distinctive aspects of divinatory practices evidenced from the Pharaonic to Roman Period. Elisabeth Sawerthal (King’s College London) provided an overview of divination practices in the Pharaonic Period, from oracles answered at a village level to those answered by the cult statue of the god during temple processions. Sawerthal then highlighted the distinction between divination as practiced and divination as narrated in literary sources – and how both manipulate power in different ways, in the latter case, as state propaganda. Andreas Winkler (Oxford) then discussed the evidence for priests as practitioners of divination from the Pharaonic to Roman Period, with particular emphasis on the education and training required to become an astronomer, astrologer, and therefore a caster of horoscopes – and that although such knowledge was protected in theory, even low-ranking priests are known to have been astrologers. Edward Love (Oxford, Würzburg) considered the ritual practices traditionally termed magical which evidence practitioners who wished to acquire foreknowledge by interacting with manifestations of the divine – either gods or transfigured spirits of the dead. By considering the emic terminology and the mechanics of these ritual practices, he discussed how practitioners conceptualised their ability to undertake ritual procedures that would result in the manifestation, or apparition, of a divine being, and the kinds of foreknowledge they wished to acquire from them.

Jonathan Stökl (King’s College, London) surveyed divination in the Hebrew Bible, in Ancient Israel, and the Hebrew Bible as prophetic, literary divination. The construction and conceptualisation of divination in biblical texts was considered, before the distinction between divinatory practices in Ancient Israel and those in the Hebrew Bible was treated in comparison with other textual sources from the Near East. The distinctions between literary prophecies as “retrospective foreknowledge” with “rhetorical theological answers” as opposed to the practices for acquiring foreknowledge attested outside of literary sources were also brought into consideration with one another, in order to highlight the difference between divination in practice, and that recalled in literary sources.

Ending the first day of the conference, James Little (Oxford) analysed the relationship between soothsayers (kāhin) in Arabia in the pre-Islamic Period, and their role in the spread of “Abrahamitic monotheism” and “Arabian nativism” during the 7th century CE. Through divination through possession by a jinn, soothsayers were sought after for their ability to interpret dreams, identifying thieves, advise on warfare, act as healers, predict the future, as well as curse or protect against curses. As a consequence, these abilities meant that certain soothsayers were sometimes the heads of their tribes, but even when they were not, they were always highly valued in their social groups.

Beginning the second day, a panel on China drew out the distinctive practices of divination and their conceptualisation attested in textual sources from particular periods in Chinese history: Ashton Ng 黃敬凱 (Oxford) considered how the historical circumstances of warring states led to different types of scepticism towards divination in Ancient China. The conceptualisation of the efficacy of divination was shown to have been particularly complex during the period of the Western Zhou: the different forms of divination were placed within a hierarchy, so that, for example, milfoil divination was seen as inferior to turtle-shell divination, while there was both scepticism that such practices could truly interpret Heaven’s will, and outright scepticism that foreknowledge could be revealed in such practices. Xiao Liqian 肖力千 (Peking University) continued the panel on China by introducing Taisu pulse divination, a practice that has long been understood as a means of diagnosing the physiological condition of patients in Chinese medicine, but which was also utilised to determine the fate of individuals by analogy to their physiological conditions. These interpretations are based on the same cosmology, and Taisu pulse divination is therefore an interesting example of the technical practices of divination that – in many cultures – appear distinct from the ritual practices for acquiring foreknowledge. Flaminia Pischedda (Oxford) concluded the panel on China with her treatment of Pre-Imperial numerological divination inscribed on bones and bamboo. Number symbols accord with symbolic symbols in Chinese writing in order to permit the divining of future matters through the method of the shuzi gua 數字卦 “numerical divinatory symbol”. This corpus of sources is extensive, but has yet to be interpreted in its own temporal frame, instead usually being understood anachronistically through the Confucian canon, and in her future research Pischedda will trace the origin of the method of the shuzi gua as a distinctive divinatory method in its own right.

Moving to Japan, Iris Tomé Valencia (Oxford) discussed the role of the nikki, “diaries” of both female and male courtiers during the Heian period, and how they were used to record and understand prophetic visions – concerning matters “from social progress to spiritual salvation”. Such dreams could be spontaneous or cultivated – the latter referring to those in which the dreamer pieces together a narrative – but they could also be requested, with a busy courtier instead sending a priest on a pilgrimage to have a dream on their behalf! Such diaries would be kept beside the sleeping courtier or priest and written in immediately after awakening. The role of dreams as involuntary forms of revelation was also discussed, and how this was seen as legitimising the prophecies revealed in the dreams. Focusing on rekisen, calendar-based divination, Matthias Hayek (Paris-Diderot) surveyed the close relationship between calendars and almanacs, and systems of revealed knowledge. As a practice that was initially limited to the court setting, from the 7th and 8th centuries onwards, by the time that divination manuals were printed in early modern Japan, diviners could be found on street-corners, offering to discern a person’s future with reference to such calendars and almanacs.

Kenneth Zysk (Copenhagen) was unable to attend in person, but his paper on the underlying divinatory structure that was common to Bharata and Semonides was read-out by Domenico Giordani and questions were taken to be forwarded on to him.

Bernhard Maier (Tübingen) surveyed the considerable number of literary sources by classical authors which describe practices among the peoples those authors termed Celts and Germans in pre-Christian Central and Western Europe. Often these sources, while tantalizing, are uncorroborated in any other sources, and none of the literary sources themselves accord with any primary archaeological evidence. Maier therefore raised the important caveat that while at least some of the descriptions of omina observed by the Celts and Germans, or the famous Welsh tree oracle, may derive from descriptions of real observations, they could also be fanciful otherings by the literary authors themselves.

William Ryan (Warburg Institute) concluded the final panel of the conference with a survey of his research on divination among the East Slavs of modern Russian, Ukraine, and Belarus made known to English-language audiences, and subsequently many other language groups through its translation, in his book Bathhouse at Midnight: An Historical Survey of Magic and Divination in Russia. From ‘marital prospects divination’, where young women would hope to find out who they would marry, to seeing one’s death in the shards of a broken mirror, Ryan surveyed a wealth of material from decades of research, making known not only practices unparalleled in other regions, but also those which could ultimately have been translated from Byzantine Greek in the Middle Ages, drawing links with the panels concerning the Ancient Mediterranean that began this conference.

There is no doubt that the collaborations still to come between the colleagues assembled for this unprecedented conference will do much to study and explain the great diversity of divinatory practices attested across all these regions and periods of time in the years to come, and we look forward to seeing the product of their future work.