In the previous post in this series, we discussed a parchment sheet from a now-lost codex kept at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (BnF), BnF Copte 129 (20) fol. 178, dated to around the 10th century, which contains several healing prescriptions. In this blog post, we will have a closer look at the first one, a fumigation prescription, which is followed by a prayer for quick childbirth:

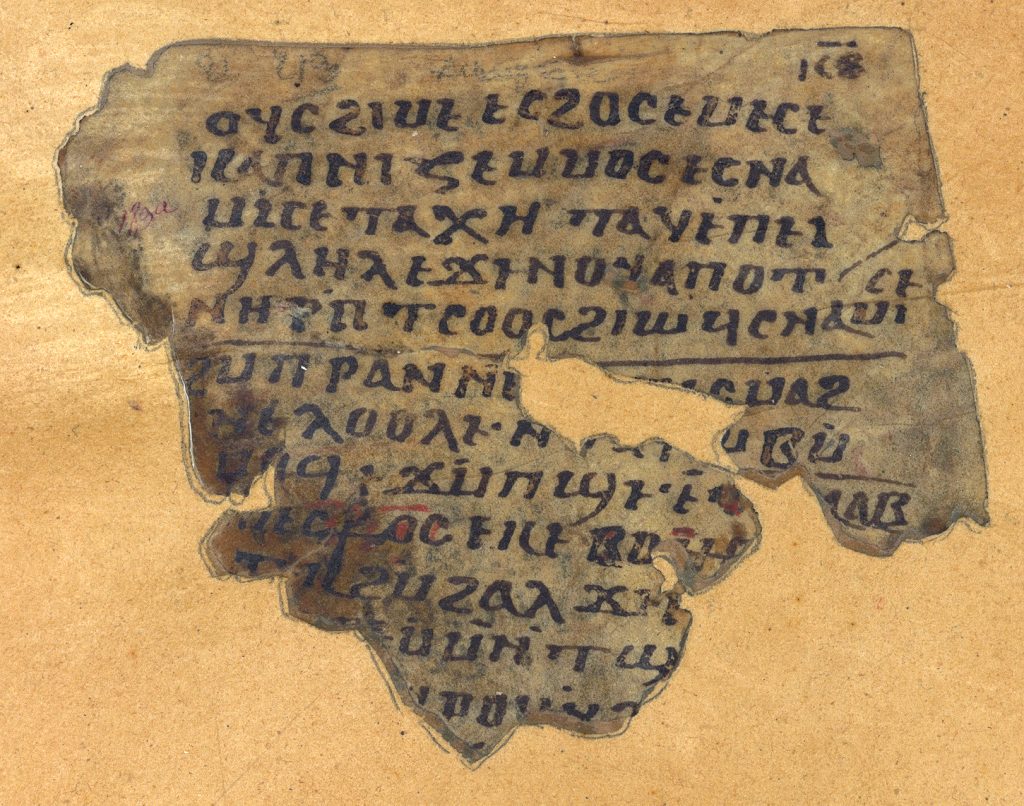

BnF Copte 129 (20) fol. 178 (134), recto ll. 1–12:

ⲟⲩⲥϩⲓⲙⲉ ⲉⲥϩⲟⲥⲉ ⲙⲉⲥⲉ ⲕⲁⲡⲛⲓⲍⲉ ⲙⲙⲟⲥ ⲉⲥⲛⲁⲙⲓⲥⲉ ⲧⲁⲭⲏ ⲧⲁⲩⲉ̇ ⲡⲉⲓϣⲗⲏⲗ ⲉϫⲉ̣ⲛ ⲟⲩⲁⲡⲟⲧⲛⲏⲣ̇ⲡ ⲧⲥⲟⲟⲥ ϩⲓⲱϥ ⲥⲛⲁⲙⲓ/ⲥⲉ | ϩⲙ ⲡⲣⲁⲛ ⲛ̇ⲓ̣̅[ⲥ̅ · ⲛ]ⲡ̣ⲉ̣ⲥⲙⲁϩ ⲛⲉⲗⲟⲟⲗⲉ · ⲛⲧ̣ⲁ̣ϥ̣ⲱ̣ⲃ ⲙ̇ⲙⲟϥ ⲉ̣ϫⲙ̇ ⲡϣⲉ · ⲉ̅ⲧ̣̅[ⲟ̅ⲩ̅]ⲁ̣̅ⲁ̅ⲃ̅ [ⲛ̣?]ⲡ̣ⲉⲥ⳨ⲟⲥ ⲉⲕⲉⲃⲟⲏ̅ⲑ̣[ca. 2] [ⲉ]ⲧⲉ̣ⲕϩⲙ̇ϩⲁⲗ ϫⲉ [ca. 5 ] ⲉ̣ⲙ̇ ⲙ̇ⲛ̇ ⲧϣ[ca. 9]ⲣⲟⲩ ⲛ̣̇ϩ̣[ca. 5]

A woman suffering in labour: Fumigate her, she will give birth quickly. Say this prayer over a cup of wine, have her drink from it. She will give birth.

“In the name of [Jesus (?)]. By (?) bunch of grapes that he pressed upon the [holy] tree of the cross, help your servant (f. sg.), daughter of (?) … !”

Here, the fragment breaks off.

In short, the recipe tells us that a woman should be fumigated and made to drink a cup of wine over which a prayer was uttered. First, we will discuss the prayer, from which only the beginning survives. The prayer hints at a metaphorical relationship between the wine drunk by the woman giving birth and the blood of Christ shed during his crucifixion, likened to “pressed grapes”, which was the wine drunk during the communion ritual. The following request “help your servant” is also found in P.MoscowCopt. 36 ll. 26–28 (= KYP T717): “Jesus Christ, help your servant, Theōna, the son of Thaplous”. Because this is a formulary rather than an applied text, the prayer indicates that the name of the patient is to be recited here. What followed this passage is, unfortunately, lost.

We will now explore the ritual practice in more detail. Drinking wine enhanced by a prayer is a common practice in healing texts in Coptic, but fumigation (in the context of uterine fumigation, a practice in which a woman sits over vapors or smoke, the source of which is, for example, burning coal) is less common, although attested. This practice is already mentioned in Egyptian medical texts from the New Kingdom and earlier, and was used to treat and diagnose various gynaecological issues, such as regulating blood flow or determining a woman’s fertility. Fumigation as a gynaecological practice is also known from Greek and Demotic medical and magical texts.

Besides the BnF text published here, three other healing prescriptions written in Coptic refer to this practice. The first text is for a woman with a painful womb, Mich. Ms. 136, p. 10 ll. 12–16 (ll. 161–165; KYP M128; recently republished by Michael Zellmann-Rohrer and Edward Love). The Michigan manuscript is also a parchment codex containing iatro-magical prescriptions, but dating perhaps as early as the fourth century. The fumigation prescription is more detailed in the manuscript from Michigan than in the one from Paris; oil and hair of an old woman are to be put on coals of sycamore, and the woman should sit over the smoke. The second text, P.Berol. 8109 (KYP M174), is a parchment codex of iatro-magical prescriptions from Egypt, written about three centuries later, containing a prescription for a woman having “blood under her” (this phrase refers to uterine bleeding). According to this text, the woman should be fumigated, but we know nothing of the context or the ingredients to be used during the procedure. The third one is a medical text recommending that a woman sit over boiled cumin if her womb is “closed” (C.Pharm.Copt. 32, no. 110; KYP M941). To summarize, two gynaecological texts indicate that a woman should sit over smoke (for a painful womb and a “closed womb”), and the two other texts (helping in childbirth, stopping flow of blood) do not specify the kind of fumigation to be performed.

The 9th-century ʿĪsā ibn ʿAlī’s book On the Useful Properties of Animal Parts, recently edited by Lucia Raggetti, contains several gynaecological fumigation prescriptions; with a man’s hair to prevent swelling of the womb, in which case this is clearly indicated as a uterine fumigation (no. 1.15c). A case to aid obstructions of the uterus, combining various ingredients with tamarisk wood (the same ingredient as in C.Pharm.Copt. 32), is rather unclear. Three versions of this particular prescription exist; in two of them, a woman “should blow [into burning coals] until smoke reaches her/so that the smoke rises towards her” and in the third, the woman should “stand over” it, so that it can enter her abdomen (no. 21.13 a, b, c). According to the same manuscript, fumigation with weasel excrement should stop uterine bleeding, fumigation with incense and blood of a hunting dog for a woman to abort (no. 8.18a, 33.2b). We can see that fumigation was used to regulate bleeding and to prevent swelling of the womb, similarly to the texts written in Coptic, but also to those written in Greek and older forms of Egyptian.

Considering these sources, it can be argued that in the Coptic medical and iatro-magical texts, the purpose of the fumigations was also a sort of manipulation of the womb. Such manipulation would result in “unlocking” the “closed” womb to ease childbirth, reduce pain in the womb, and regulate the flow of blood, which could result in releasing the pressure from the womb that causes pain.

Bibliography:

For some Greek medical sources regarding fumigation, see : Hippocrates, The Nature of Women, 4, 3, 5, 6, 14, 25, according to the edition by P. Potter, Hippocrates, Generation. Nature of the Child. Diseases 4. Nature of Women and Barrenness. Loeb Classical Library 520 (Cambridge, MA – London, 2012). Hippocrates, Diseases of Women 1, 34; 75, 2; Diseases of Women 2, 94, according to the edition by P. Potter, Hippocrates, Diseases of Women 1–2. Loeb Classical Library 538 (Cambridge, MA, 2018).

For a selection of Egyptian medical sources regarding fumigation, see: P. Kahun 1: 1–5, 2: 5–8; 5: 15–22; perhaps also 20: 3–6 (?), P. Ramesseum IV.C ll. 17–24, Edwin Smith Papyrus verso 20: 20,13–21,3; P. Ebers 793: 94,3–94,5; P. Ebers 795: 94,7–94,8; P. Carlsberg VIII 5 1,6–2,1; 3038 Berlin 195: 1,7–1,8. For translations and context of these texts, see E. Strouhal, B. Vachala, and H. Vymazalová, The Medicine of the Ancient Egyptians: Surgery, Gynecology, Obstetrics, Pediatrics (Cairo – New York, 2014).

Grons, A. Medizinische Rezepttexte in koptischer Sprache (C.Pharm.Copt.). Archiv für Papyrusforschung und verwandte Gebiete – Beiheft 56. Berlin: De Gryter, 2025.

Faraone, C.A. “Magical and Medical Approaches to the Wandering Womb in the Ancient Greek World.” Classical Antiquity 30.1 (2011): 1- 32.

Preininger, M. “BnF Copte 129 (20) fol. 178: Three Healing Prescriptions.” Archiv für Papyrusforschung und verwandte Gebiete 68, no. 2 (2022): 344-357.

Raggetti, Lucia. ʿĪsā ibn ʿAlī’s Book on the Useful Properties of Animal Parts: Edition, translation, and study of a fluid tradition. Berlin – Boston: De Gryuter, 2018.

Zellmann-Rohrer, M.W. and E.O.D. Love. Traditions in Transmission. The Medical and Magical Texts of a Fourth-Century Greek and Coptic Codex (Michigan Ms. 136) in Context. Archiv für Papyrusforschung und verwandte Gebiete – Beihefte 47. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2023.