For this year’s first blog post, we start a new series looking at angels in Coptic Magic. As an introduction, this first post provides a brief discussion of the concept of angels and their importance in various ritual and literary traditions, as well as an overview of the main groups of angels found in Coptic magical texts. The following posts in this series will focus on specific groups of angels and individual angels, discussing their roles, names, and descriptions.

In the world of Late Antique and early Medieval Egypt, which was predominantly Christian from the fourth to the ninth centuries, angels can be defined as incorporeal beings made of fire and spirit, who served as God’s agents and messengers (Psalm 104:4). In the imaginary of Christian Egypt, the actions of angels were believed to have actual effects on the material world, enacting God’s will. Accordingly, angels could also act on behalf of humankind. Their assistance could be secured in several ways, for example, through prayers, incantations, and other rituals, which is why they appear prominently in Coptic magic.

While Coptic magical texts are witnesses to some new and original traditions about angels, they also drew upon, and evolved together with, older and contemporary traditions, including the Greco-Egyptian magical papyri, Jewish private ritual, orthodox Christian liturgical practice, and Christian literature. It is therefore important to mention these briefly before moving on to the Coptic magical material.

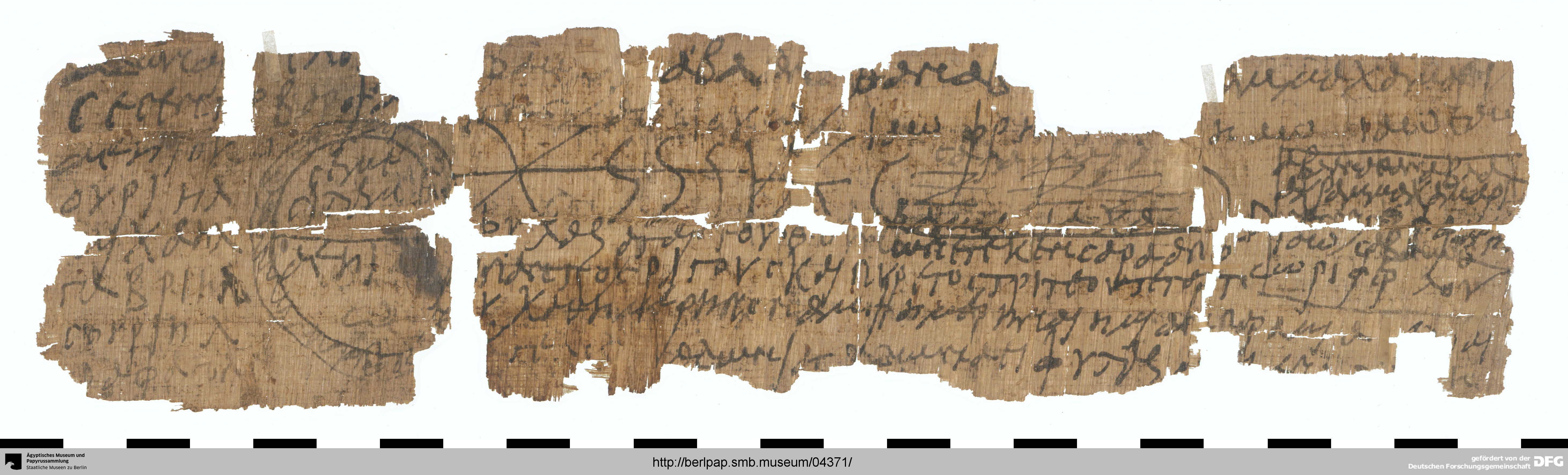

First, the Greek term angelos had the basic meaning of “messenger” and had no original Christian connotation. It was used already in Greek texts, for instance, to refer to gods such as Hermes who served as a messenger for Zeus. In the Greek magical papyri, beings characterized as “angels” appear as intermediate beings serving as agents of higher powers. Several Greek magical texts also include lists of angels and archangels known from Judeo-Christian traditions. For example, the papyrus amulet Berlin P. 21165, dated to the third or fourth century, contains a list of angels (Ouriel, Michael, Gabriel, Souriel, and Raphael) and calls upon “Eloai, angel Adōnias, Adōnaei” to protect Touthous, son of Sara, from shivering and fever.

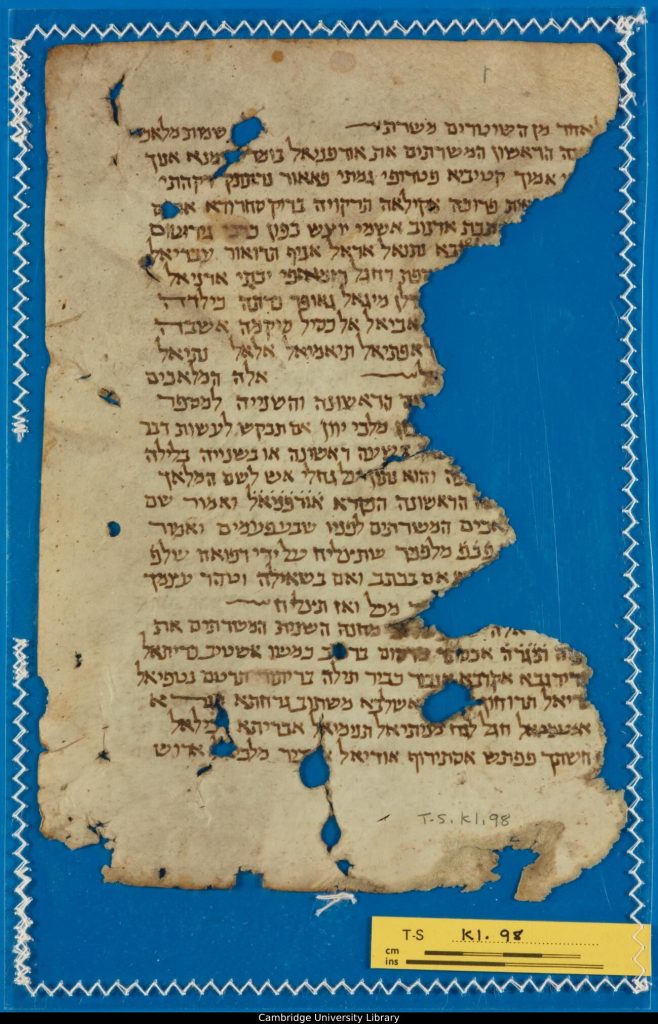

While this inclusion of originally Jewish elements in non-Jewish texts sometimes makes it difficult to identify Jewish magic among Egypt’s surviving papyrological corpora, one notable example is a work known as the Book of Secrets (Sefer ha-Razim). The earliest surviving copies of this work are attested in later Hebrew and Judeo-Arabic manuscripts from the Cairo Genizah, from the late tenth century onwards, but some scholars date the work itself as early as the fourth century. This book contains a detailed description of the seven heavens, with their inner structures. For each heaven, we get lists of angels found in each sub-section, with their main features and tasks, as well as a wide range of rituals used to make these angels fulfill one’s needs.

The organization of angels in groups and classes, which have distinct characteristics and are found in specific heavenly locations, is also a common trope of Christian ritual practices and literature. Egyptian liturgical texts of Late Antique origin, especially anaphoras, the central prayers of the Eucharist service, include lists of angelic classes (for example, thrones, dominions, and powers), often with a particular focus on the cherubim and the seraphim, all assembled as an angelic choir glorifying God. Angelic hierarchies also appear in early Christian works, notably in Pseudo-Dionysus the Areopagite’s On the Celestial Hierarchy (ca. fifth century CE), where the author describes nine angelic orders grouped in three triads, with the first, higher triad consisting of the seraphim, cherubim, and thrones, the second comprising the dominions, virtues, and powers, and the third the principalities, archangels, and angels.

Finally, several Christian apocryphal works, of which many are attested in Coptic, are dedicated to individual angels, or groups, such as the archangels Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, or the Twenty-Four Presbyters. These works often emphasize the protective power ascribed to the angels’ names, which is generally important in magical practices as well. For example, in Pseudo-Timothy of Alexandria’s On the Feast of the Archangel Michael, we are instructed to write the name of Michael on the walls of our houses, the edge of our garments, our tables, plates, and cups, so that it may serve as protection against evil.

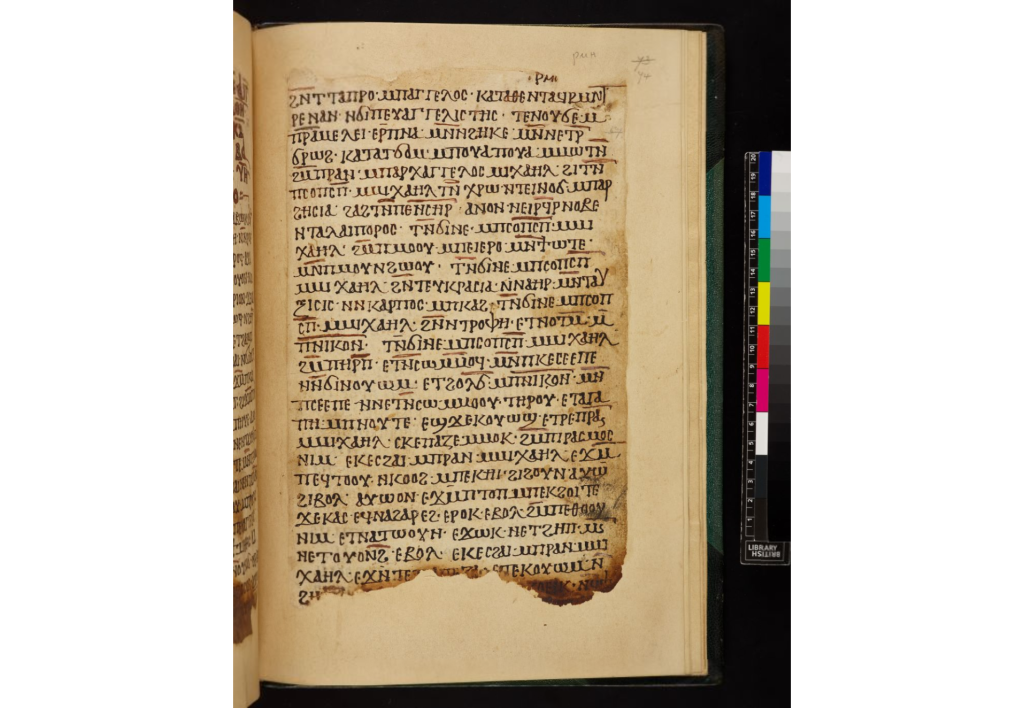

As for Coptic magical texts, they also attest to this tradition of describing the celestial realm and classifying its inhabitants. A distinctive feature of a group of Coptic texts known as “magical liturgies” is to provide detailed descriptions of the divine court, centered around God in heaven, with all the angels surrounding and serving him. Good examples of these texts are the so-called Endoxon of the Archangel Michael and Prayer of Mary in Bartos, both attested in several Coptic manuscripts. The groups and classes of angels presented in these descriptions sometimes, but not always, mirror angelic lists and hierarchies found in other Christian sources. However, the main focus of the Coptic magical texts is usually on the secret names of these angels and the powers ascribed to them, rather than the hierarchy per se.

In prime position are the Twenty-Four Presbyters, described as surrounding and praising God in Revelation 4. Some magical texts describe them sitting on twenty-four thrones, with twenty-four crowns upon their head, drawing back to the biblical passage. Then come the Four Bodiless Living Creatures drawing the throne of God (Ezekiel 1 and 10; Revelation 4:6–8). They are often described as cherubim and sometimes accompanied by the seraphim from Isaiah 6. The seven archangels, of course, also appear high up in the hierarchy. While their number and exact names may vary (as will be discussed in a later post), lists usually feature at least Michael, Gabriel, and Raphael, the three angels mentioned in the Bible.

Other members of the divine court are the angels appointed over God’s body parts, such as Orphamiel, the great finger of the Father. We also encounter the angels Harmoziel, Oroiael, Daueithe, and Eleleth, usually identified as the four luminaries of the Autogenes from Gnostic traditions—although, as we will see in another post, this may not always be the case. There are also other groups known from classic angelic hierarchies, such as thrones, authorities, and powers. In Coptic magical texts, these often have names, sometimes well-known voces magicae such as sesengen barpharanges or akramachamari, or names ending in -ēl, following the model of other angelic names. Finally, not all angels were in heaven. Coptic magical texts also feature the angels responsible for divine punishments in Hell, known as Tartarouchos and Temelouchos in Late Antique apocalyptic traditions.

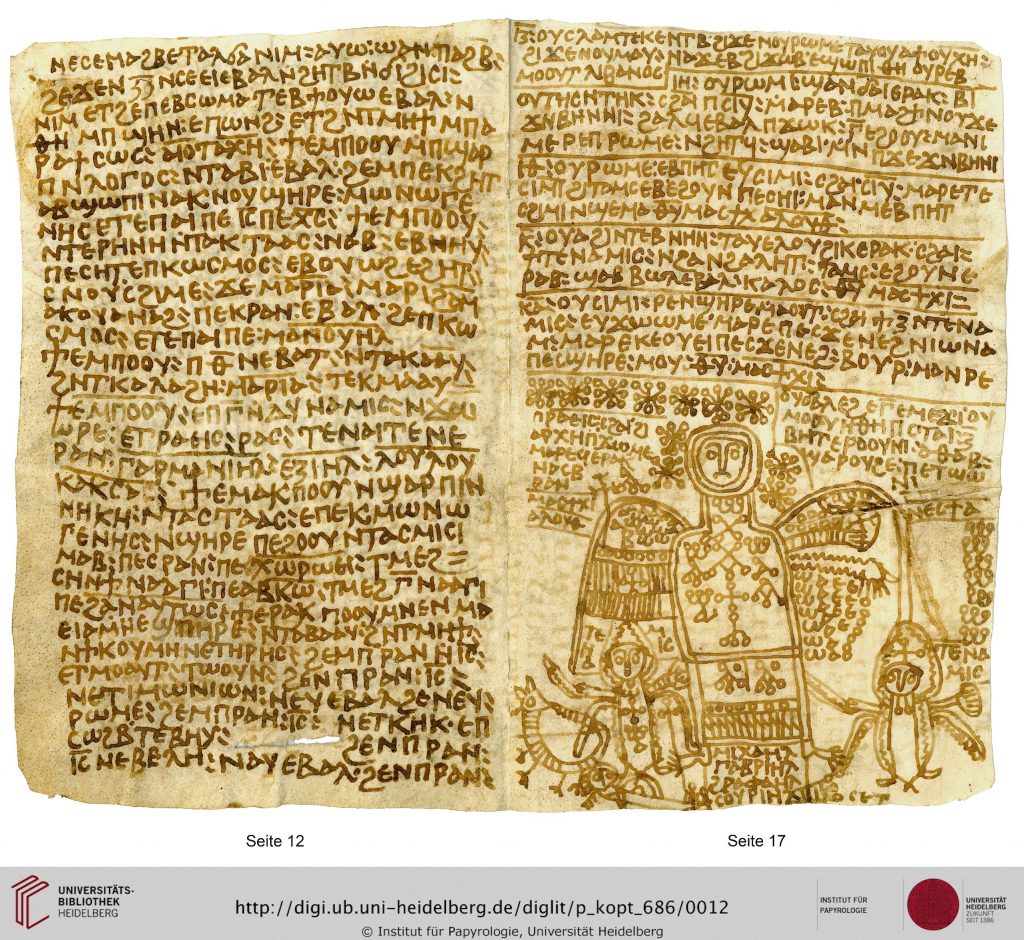

Of course, all these angels are not always included together in lists and long descriptions of the heavenly court in Coptic magic. They are also invoked, in groups or individually, as protectors and helpers; they sometimes appear as protagonists in narrative charms; they are even depicted in drawings that can be copied onto amulets. The surviving material thus suggests that practitioners had access to this wide array of angelic beings who could be called upon in various ways, depending on the clients’ needs. In time, it seems that some angels developed specializations, and we can see a correlation between the angels invoked and the goals of the texts. For example, the Twenty-Four Presbyters appear mainly in healing and protective charms, while Tartarouchos and Temelouchos are invoked in curses and love spells.

In the next posts in this series, we will have a closer look at some of the angels mentioned above, see in what types of Coptic charms and spells they appear, what their roles are in these texts, how they are described, what secret names are used to invoke them, and how these elements found in the Coptic magical texts correspond to larger traditions about these angels in Christian ritual practices and literature.

Bibliography and Further Readings

Budge, E. A. W., Miscellaneous Texts in the Dialect of Upper Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1915. URL

Editions and translations of several texts from British Library MS Or. 7029, including Ps-Timothy of Alexandria’s On the Feast of the Archangel Michael.

Dosoo, K. “Ministers of Fire and Spirit: Knowing Angels in the Coptic Magical Papyri”. In Inventer les anges de l’Antiquité à Byzance, ed. by D. Lauritzen. Paris: Association des Amis du Centre d’Histoire et Civilisation de Byzance, 2021, 403–434. URL

Fauth, W. Jao-Jawhe und seine Engel: Jahwe-Apellationen und zugehörige Engelnamen in griechischen und koptischen Zaubertexten. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014. URL

Hoffmann, M. R. “Systematic Chaos or Chain of Tradition? References to Angels and ‘Magic’ in Early Jewish and Early Christian Literature and Magical Writings”. In Representations of Angelic Beings in Early Jewish and in Christian Traditions, ed. by A. Tefera and L. T. Stuckenbruck. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2021, 89–129.

Keck, D. Angels and Angelology in the Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998.

Especially pp. 53–65 for an overview of the angelic orders and their biblical precedents.

Kraus, T. J. “Angels in the Magical Papyri: The Classic Example of Michael the Archangel.” In Angels: The Concept of Celestial Beings, ed. by F. V. Reiterer, T. Nicklas, and K. Schöpflin. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2007, 611–627. URL

Kropp, A. Ausgewählte koptische Zaubertexte. Einleitung in koptische Zaubertexte. Vol. 3. Bruxelles: Édition de la Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, 1931. URL

Especially pp. 67–95 for a discussion of angels in Coptic magical texts.

Mihálykó, Á. T. “Mary, Michael and the Twenty-Four Elders: Saints and Angels in Christian Liturgical and Magical Texts.” In Proceedings of the 29th International Congress of Papyrology. Lecce, 28 July-3 August 2019, ed. by M. Capasso, P. Davoli, and N. Pellé. Lecce: Centro di Studi Papirologici dell’Università del Salento, 2022, 722-773. URL

Peers, G. Subtle Bodies: Representing Angels in Byzantium, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001.

A helpful introduction to angels in Late Antique Christianity.

Rorem, P. Pseudo-Dionysius. A Commentary on the Texts and an Introduction to Their Influence. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993.

Especially pp. 47–90 on the Celestial Hierarchy.

Sepher ha-Razim: The Book of Mysteries, critical ed. and transl. by M. A. Morgan, Chico, CA: Scholars Press, 1983.

An accessible edition of this text.