The Coptic Magical Formularies project finished its first full year in 2025, with some big changes. Former principal investigator Korshi Dosoo started a new position at the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in France, but he will continue to work with the Coptic Magical Formularies project as an external collaborator. Markéta Preininger will stay on as principal investigator, and the team has grown bigger, as Sophie-Charlotte Gissat has joined as a research assistant. Roxanne Bélanger Sarrazin, currently a fellow on our partner project MagEIA has also joined as a collaborator, and will continue to work as a full member of the team after her fellowship.

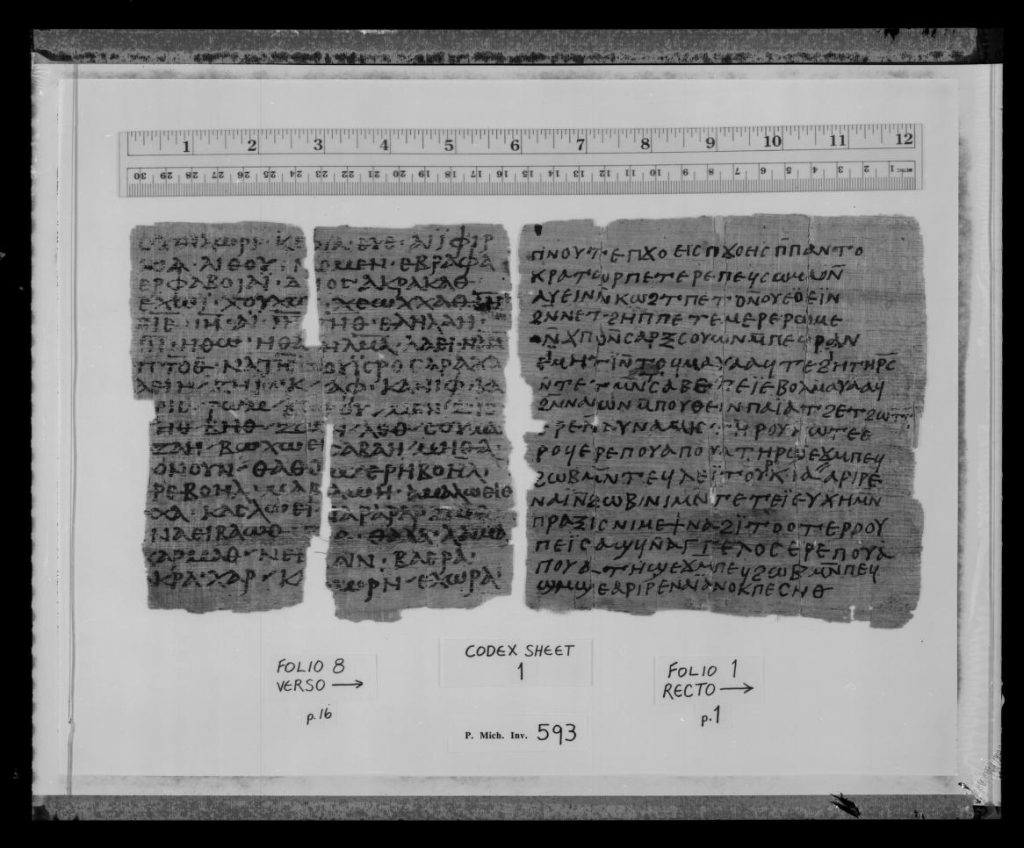

With all of these changes, it’s been a while since our last database update, but we have a big one in the works, with editions of most of the main texts of two of the big surviving archives of Coptic magical papyri, the British Museum Portfolio, and Michigan Wizard’s Hoard, nearly ready. As often happens when we revisit texts first published nearly a hundred years ago, these editions will substantially update and correct the older interpretations; we have even managed to find and decipher an encoded text previously misunderstood as meaningless magical words! We are also working on updating the editions of papyri which are already online so that they incorporate the corrections and fuller notes found in the published Papyri Copticae Magicae volume 1. All of this will be available in Kyprianos in early 2026.

Our project is also part of a larger network of international projects exploring ancient magic and the Coptic language, and over the last year these have been very active. In addition to working with our sister project MagEIA in Würzburg, we are collaborating with the Coptic Scriptorium to lemmatise Coptic magical texts, allowing them to be searched and analysed for linguistic information. We are also working with the new Phoinix project, which is digitising magical gems, to allow them to be searched on both platforms. We are collaborating with our colleague Panagiota Sarischouli (Aristotle University of Thessaloniki) on her newly-funded NOMINA project, which will create an online database of voces magical (“magical words”), first in Greek texts, but later including other languages, including Coptic. Finally, we have been working with the Chicago-based Transmission of Magical Knowledge project on the publication of the second volume of the Greek and Egyptian Magical Formularies (GEMF), looking in particular at the ‘Old Coptic’ texts, some of the earliest surviving Coptic manuscripts, and evidence for a syncretistic magical practice combining Greek, Egyptian, and Christian influences.

In the last year, team members submitted a good many articles (and even a book or two…), but only four appeared in print and/or online:

- Bélanger Sarrazin, Roxanne. “Prayer of Mary at Bartos.” e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha. https://www.nasscal.com/e-clavis-christian-apocrypha/prayer-of-mary-at-bartos/ (open access)

The ‘Prayer of Mary at Bartos’ is one of the most important healing prayers in the tradition of the Alexandrian Church, preserved in many copies in Coptic, Arabic, Ethiopic, and a single Greek copy. This entry for the online reference work e-Clavis: Christian Apocrypha of NASSCAL (North American Society for the Study of Christian Apocryphal Literature) provides an overview of the prayer in its two major traditions, and gives a comprehensive published and online bibliography for the text and its manuscripts. - Dosoo, Korshi. “Magical Names: Tracing Religious Changes in Egyptian Magical Texts from Roman and Early Islamic Egypt”, Archiv für Religionsgeschichte 26.1 (2024): 69–144. https://www.degruyter.com/document/doi/10.1515/arege-2024-0005/html (open access)

Magical texts from Egypt, written in both Greek and Coptic, provide us with a view of religious practices in Egypt quite different from that found either in canonical or documentary texts. This article explores two ways in which the names they contain might help us to map the cultural transformations of the fourth- through twelfth centuries. The first is by looking at the names of gods, angels and other superhuman beings, tracking the decline of the ‘pagan’ Graeco-Egyptian deities, and the rise of the Christian pantheon, leaving with a few interesting holdouts. The second is by looking at the names of the individuals mentioned in magical texts – the clients for whom amulets were created, and the victims targeted by love spells and curses. Do the onomastic changes in magical texts follow the general trends of naming practices over this period, or attest to a magical subculture with its own naming habits? And do the religious contents of the magical texts correspond with the implied confessional belongings of the people for whom they were created? Did Christians use Christian magic, or do we find more complex patterns – Christians using ‘pagan’ magic, or Muslims using Christian magic, for example? - Preininger, Markéta. “Taxonomies of Illnesses and the Dynamics of Cursing and Healing the Body in Christian Egypt”, Trends in Classics 17.1 (2025): 162–183. https://doi.org/10.1515/tc-2025-0008 (open access)

The Coptic magical corpus, a collection of manuscripts produced in Egypt between the fourth and twelfth centuries CE for private ritual purposes, provides a rich source concerning non-institutional and private healing practices. Because the magical healing manuscripts from the corpus are not self-reflexive, unlike Hippocratic writings, the work of interpretation and reconstruction of the taxonomies of the healing practices is left to modern researchers. The researcher has several etic interrelated categories to understand and interpret: symptoms (i.e., tooth pain), causes (i.e., evil spirits), and treatments (i.e., binding of an amulet to the forearm). In understanding the relationships between these three categories, the modern reader might more easily comprehend the logic of healing practices witnessed by the corpus. However, not only healing texts provide an insight into the causes of diseases, but also curses causing them (called here health curses). In this article, I both of these corpora are discussed and compared, focusing especially on lists of illnesses and agents causing them, as they appear in both healing texts and health curses. - Dosoo, Korshi. “Gatherings of Words: Notes on Books of Magic from Roman Egypt”, West 86th 32.1 (2025) 31-38. https://doi.org/10.1086/737596

Unlike modern depictions of magical books as inherently powerful objects, handbooks from Roman Egypt are practical guides that can be fruitfully explored by attention to their physical details. This study begins by contrasting this material dimension with iconic-sacred, semantic, and expressive-performative perspectives on manuscripts before exploring the production and circulation of handbooks, starting from their basic unit, the magical recipe, and discussing how these were built up into larger collections.

As always, if you would like to read an article produced by a team member, but don’t have access to it, please feel free to contact us to receive an offprint.

In addition to these academic articles, we’ve started to get back into the swing of blogging, with two new series of blog posts, Animals in Coptic Magic, and Three Healing Prescriptions from a Now-Lost Codex, which we’re planning to continue into 2026, and Korshi Dosoo has written a couple of guest posts on the MagEIA project blog, which you can read here.

In addition to our writing, the team members also took part in many conferences and workshops, among them the second symposium organised by our colleagues in the MagEIA project, which brought together specialists on ancient and mediaeval Eurasian and African magic from around the world. We also took some time out to promote the first volume of Papyri Copticae Magicae, with New Books in Late Antiquity host Lydia Bremer-McCollum kindly inviting us to an interview to discuss the writing and contents of the volume. Volume two is well under way, and we hope to soon be able to share more concrete news about our plans. In the meantime, thanks to everyone who has reached out to us, read our work, and supported us over the last year!