In our first post on Christianity in magic, we discussed AMS 9, a large book filled with amuletic texts. Among these were the first verses (incipits) of five texts from the Bible – the gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, and Psalm 90 (Western Psalm 91). As we noted then, these were intended to be copied onto smaller objects and worn as a way to protect the body from sickness, demonic attacks, and misfortune. This week, we’ll discuss the use of the Bible in “magical” practice in a little more detail. This discussion will draw extensively upon a recently published study of such practices, Scriptural Incipits on Amulets from Late Antique Egypt by Joseph E. Sanzo (2014), which we recommend to anyone looking to learn more.

The Bible was, of course, a vitally important text to Christians, considered as divinely revealed scripture. Ordinary Christians would likely have encountered it regularly as a living text read aloud during the annual liturgical cycle, in which most of the New Testament, and parts of the Old Testament, in particular the Psalms, would have been heard during the sacred rituals which took place in church – the Eucharist, baptism, funerals, and so on. These would have been just one part of a rich and sacred sensory experience accompanied by the smell of incense and glimpses of paintings of saints and angels lit by oil lamps.

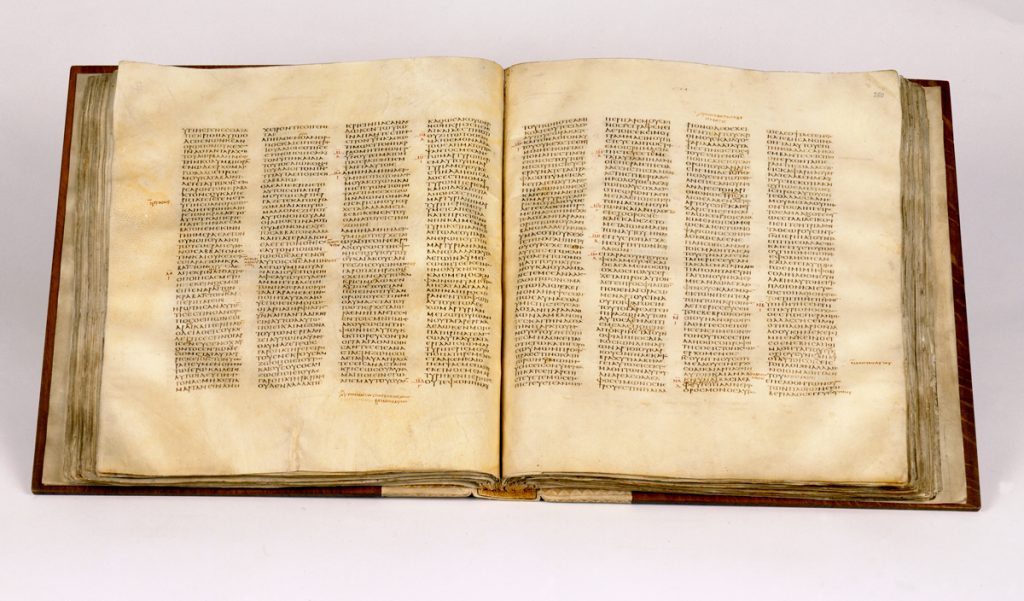

Unlike today, the Christian scriptures were not generally collected in a single volume, but rather in smaller collections, such as codices containing the four canonical gospels. Owning even such a smaller book would have been impossible for most Christians, even if they could read – the cost of the materials, copying, and binding of such a book would have been considerably more than a manual worker’s annual income in many cases. They would nonetheless have seen copies of the Bible in church, often richly decorated, with painted illustrations, carried by deacons in jewelled covers, and treated with the respect due to sacred objects. A story from the Life of Shenoute describes how, during the Council of Ephesus (431 CE), the heretic archbishop Nestorius revealed his wickedness when he found a copy of the Gospels on his chair and put them on the floor so that he could sit down. Shenoute, a lowly Egyptian abbot, picked up the Gospels and punched the archbishop off his chair, earning the applause of the entire synod. Whether this story is true, or a fiction invented to demonstrate the piety of Shenoute, it shows the respect which Egyptian Christians felt the Scriptures were owed.

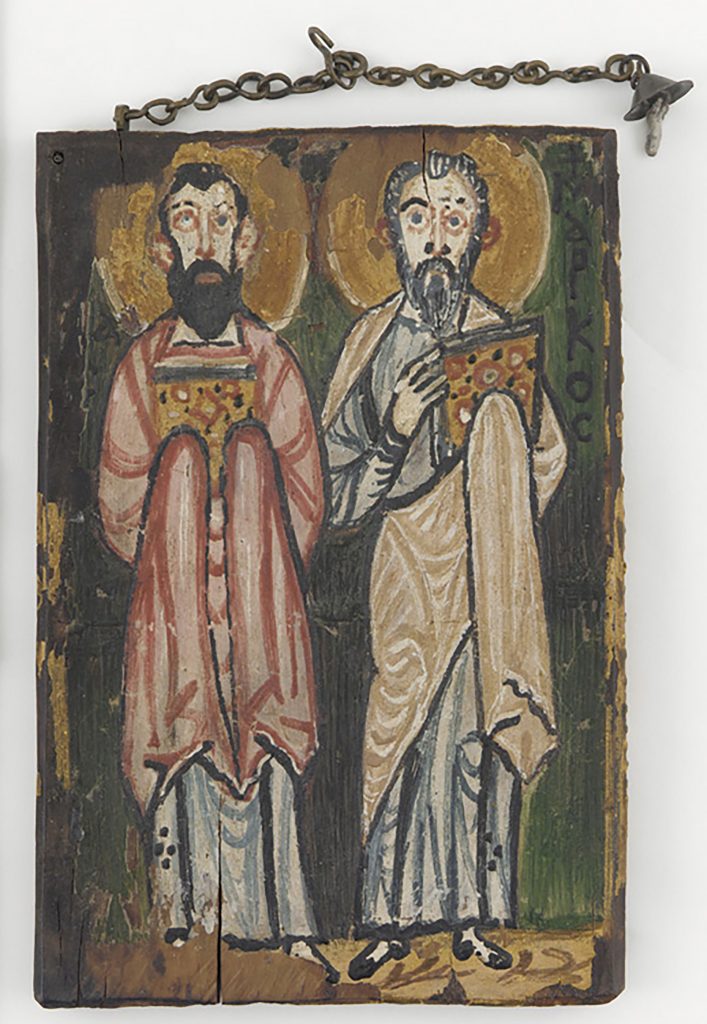

The front and back covers of the Washington Gospel Manuscript (4th-5th century CE), a copy of the four canonical Gospels. These covers are painted on wood, and depict the evangelists as bearded men holding their books in their hands.

Copyright Freer Gallery of Art

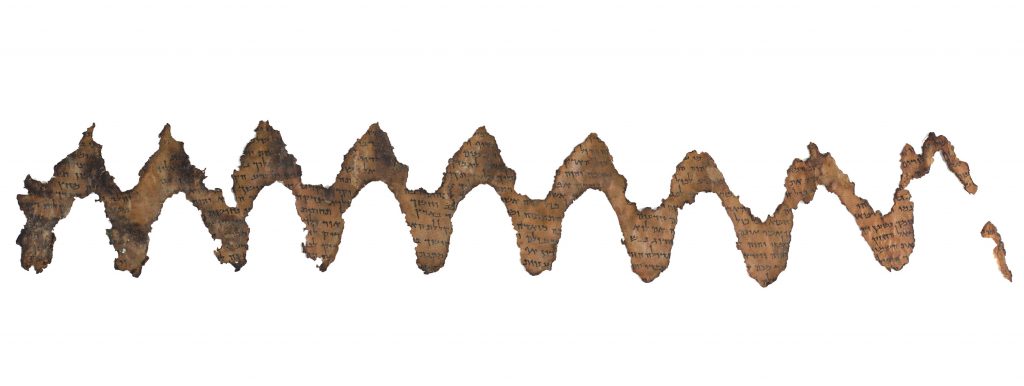

Using scriptural texts as amulets was therefore a way of drawing the sacred power of the Bible into the lives of individual Christians. While they might not be able to afford a copy of the Gospels in their entirety, they could wear their first lines as a way of warding off evil and misfortune. This use of sacred texts was not uniquely Christian – we have evidence of Greek speakers in Egypt using passages from Homer in amulets and other magical contexts, while evidence from the Dead Sea scrolls and Cairo Genizah shows that Jewish communities were using the Psalms as a form of protection from evil spirits before Christianity began, and continued to do so even after Christians appropriated their scriptures. Indeed, since the first Christians came from the Jewish community, it is likely that the amuletic use of scripture among Christians was at least partly inspired by its use in Judaism. The most common Psalm found in amulets, Psalm 90, is the same one which we often find in Jewish contexts.

He who lives by the help of the Most High, in a shelter of the God of the sky he will lodge. He will say to the Lord, “My supporter you are, and my refuge; my God, I will hope in him…”

Psalm 90.1-2 (Septuagint version)

New English Translation of the Septuagint (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Image created by Shai Halevi

As we have noted, though, the most common type of scriptural amulet contains the titles or first verses of the four Gospels: Sanzo lists 25 surviving examples from late antique Egypt in his catalogue, in Greek, Coptic, and even Latin. Traditionally, scholars have understood these incipits as working through the principle of pars pro toto (“part for the whole”) – the shorter passages stand in for the whole sacred scriptures, condensing the colossal power of the Word of God into a few short lines. Sanzo suggests something a little subtler, pars pro parte (“part for part”). Instead of evoking the whole Bible, he suggests that these amulets are often intended to draw upon specific parts of particular books of the Bible, which could be seen as a rich “toolbox” from which particular citations could be selected as needed. As evidence of this, he cites a passage from Evagrius of Pontus (345-399 CE):

Now, the words that are required for speaking against our enemies, that is, the cruel demons, cannot be found quickly in the hour of conflict, because they are scattered throughout the Scriptures and so are difficult to find. We have, therefore, carefully selected words from the Holy Scriptures, so that we may equip ourselves with them and drive out the Philistines forcefully, standing firm in the battle, as warriors and soldiers of our victorious King, Jesus Christ.

Evagrius of Pontus, Talking Back Prologue, 3

Rather than calling upon the whole Bible, then, the incipits of Psalm 90 would draw specifically upon the power of that song, which promises that God will protect those who take refuge in him from arrows, demons, and armies of thousands.

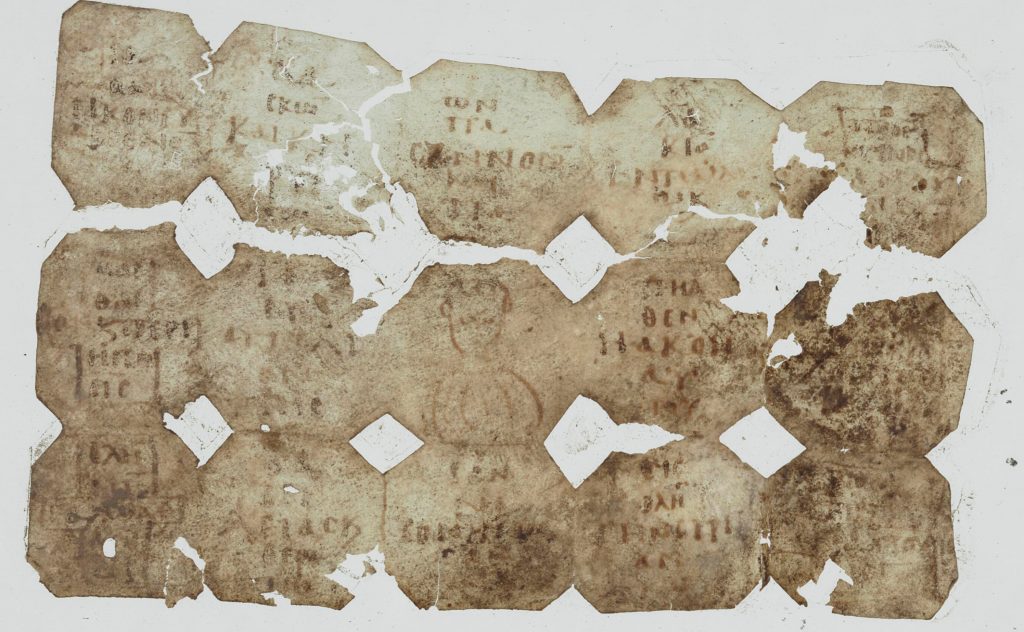

So what do the Gospel incipits refer to? Sanzo proposes that they draw upon specific stories from the life of Jesus, those found in the canonical Gospels, and even perhaps those outside of the them. One famous Greek amulet which cites the Gospel of Matthew gives itself the title “Curative Gospel According to Matthew” (P.Oxy. VIII 1077). This focus on the healing aspects of Jesus’ life would be very appropriate for someone suffering from, or scared of, a potentially deadly fever – Jesus did not only preach and die on the cross, but was also said to have healed the blind, the deaf, the lame, and “every sickness and every malady” (Matthew 4.23). By citing just a few lines, an amulet could “magically” contain within it all the narrative power of Jesus’ healing ministry.

Special Collections and Archives, Trexler Library. Muhlenberg College

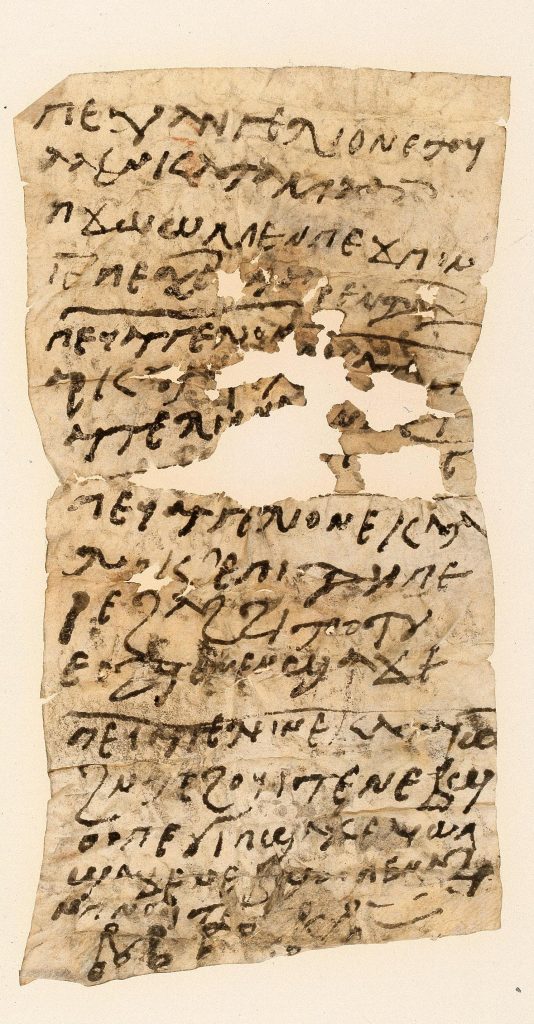

An interesting example of such an amulet is P.Mich. inv. 1559, a small sheet of parchment dating from the seventh or eighth century CE. It contains the titles and first lines of the four gospels, and in the same canonical order used by modern churches:

The Holy Gospel according to Matthew. The book of the generation of Jesus Christ, the son of David.

P.Mich. inv. 1559 ll.1-17

The Gospel according to Mark. The beginning of the Gospel of Jesus Christ.

The Gospel according to Luke. Since many have undertaken to write words.

The Gospel according to John. In the beginning was the Word and the Word was with God

Examining it closely, we can see that it was folded many times to produce a tiny bundle only a centimetre or two in each dimension. This could then have been bound with a thread, or put inside a small leather pouch, and worn as a necklace or bracelet. Interestingly, and uniquely, this amulet also contains, below the gospel incipits, a series of five symbols resembling Greek letters with circles at their points – these are the signs known as kharaktēres, commonly found on magical objects. This seems to imply that the person who copied this text saw a relationship between amulets consisting of gospel citations, and more typical “magical” texts which contained strange magical names and directly adjured various angelic and demonic powers.

Image from the Michigan Papyrus Collection

So, is the use of Biblical amulets a form of magic? An interesting perspective is found in the writings of Augustine, bishop of Hippo in modern Algeria, which Sanzo also cites. In a Latin sermon delivered in 407 CE, he tells his audience:

When your head aches, we praise you if you place the gospel at your head, instead of having recourse to an amulet. For so far has human weakness proceeded, and so lamentable is the estate of those who have recourse to amulets, that we rejoice when we see a man who is upon his bed, and tossed about with fevers and pains, placing his hope on nothing else than that the gospel lies at his head; not because it is done for this purpose, but because the gospel is preferred to amulets.

Augustine of Hippo, In Evangelium Joannis Tractatus 7.12

The word used for amulets is ligaturae, literally “tied objects”, probably referring to amulets hung from the neck or tied around the wrist or arm. He says that rather than using them, it is better to place the Gospel at the head of sufferers; although he does not seem sure that they will effect a cure, he certainly thinks that using “amulets” is risky for the soul. Here it is unclear whether Augustine is referring to an entire copy of the Gospels, or just a part, but other authors tell us explicitly that Christians sometimes wore the Gospels around their neck like amulets, and, given the difficulty of copying the entire set onto something small enough to be worn, it seems likely that here “Gospels” often means Gospel citations, perhaps incipits. For Augustine, then, there is clearly a difference between the healing use of the scriptures and the use of illegitimate “amulets”, but it is not completely clear what that is. As we have seen, both could be tied around the neck or arm to protect from or curse disease, and a similarity between “magical” and “Biblical” amulets is suggested by both the use of kharaktēres in P.Mich. 1559 and Augustine’s understanding of one as a substitute for the other. In future posts we will try to explore more deeply how Christian writers tried to distinguish legitimate ritual from “magic”, but for now we hope we have shown why it might be important for scholars to consider all kinds of amulets together.

Acknowledgements

*I would like to thank Joseph E. Sanzo for his helpful comments and corrections on this article. Any mistakes which remain are my own.

References and Further Reading

de Bruyn, Theodore. Making Amulets Christian: Artefacts, Scribes, and Contexts. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. URL

Another recent study of Christian “magical” artefacts, focusing on their material aspects.

Luijendijk, AnneMarie. Forbidden Oracles? The Gospel of the Lots of Mary. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014. URL

The publication of a “lot oracle” with the title ‘Gospel of the Lots of Mary’. Luijendijk’s discussions of the materiality and meaning of gospels in Late Antique Egypt (18-25, 51-56) were very useful in writing this post.

Sanzo, Joseph E. “Ancient Amulets with Incipits: The Blurred Line Between Magic and Religion”. Bible History Daily (1/6/2018) URL

A more in-depth, but still highly accessible, overview of Joseph E. Sanzo’s theory of incipits in his own words.

Sanzo, Joseph E. “Magic and Communal Boundaries: The Problems with Amulets in Chrysostom, Adv. Iud. 8, and Augustine, In Io. tra. 7,” Henoch 38.2 (2017): 227–46.

A deeper look at Christian constructions of magic, providing further context for the Augustine citation used here.

Sanzo, Joseph E. Scriptural Incipits on Amulets from Late Antique Egypt Text, Typology, and Theory. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2014. URL

The most complete study of scriptural incipits from Egypt, and the inspiration for most of this post.

2 Comments

Joe Slater

Interesting! I think ligaturae must be in the same family as kame’ot, amulets that were popularly used by Jews in Talmudic times. We know something of the form that kame’ot took because the authors of the Talmud were concerned that someone finding an unknown object that *looked* like tefillin (phylacteries, formal religious artefacts strapped to the arm and head) might have merely found a kame’a.

Perhaps the category of “scripture in a form that may be tied to one’s body” was simply an idea that occurred more than once, maybe all these have a common origin, or maybe (which would be very interesting!) ligaturae originated in imitation of phylacteries. Are ligaturae ever criticised in connection with Judaising practices?

Korshi

Thanks for this fantastic comment and question, I’ll have to investigate the difference between tefillin and kame’ot in the Talmud! Jewish amuletic practice is a little outside my specialty, but there is indeed at least one mention of “illegitimate amulets” being connected with Judaising practices – Joseph E. Sanzo discusses a sermon to this effect by John Chrysostom in his article “Magic and Communal Boundaries: The Problems with Amulets in Chrysostom, Adv. Iud. 8, and Augustine, In Io. tra. 7” (https://www.academia.edu/36333673/_Magic_and_Communal_Boundaries_The_Problems_with_Amulets_in_Chrysostom_Adv._Iud._8_and_Augustine_In_Io._tra._7_Henoch_39_2_2017_227_46).

Chrysostom is writing in Greek, so he talks about periammata rather than ligaturae, but he probably means something quite similar.