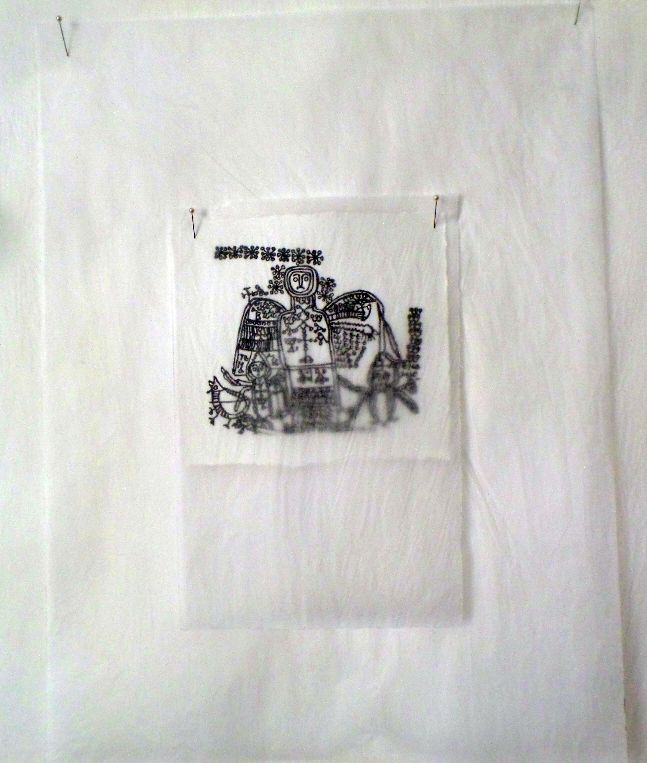

Image by Robert Campbell Henderson.

On the 11th-12th of May 2019 our project participated in our first public event, the opening of the exhibition Tracés temporels et manuscrits magiques at the Atelier Mélusine in La Trimouille in Nouvelle-Aquitaine, France. This show was a way for us to present Coptic magical manuscripts from another angle – treating their images as artistic creations, and using them as a way to explore how ancient magic was practiced and experienced.

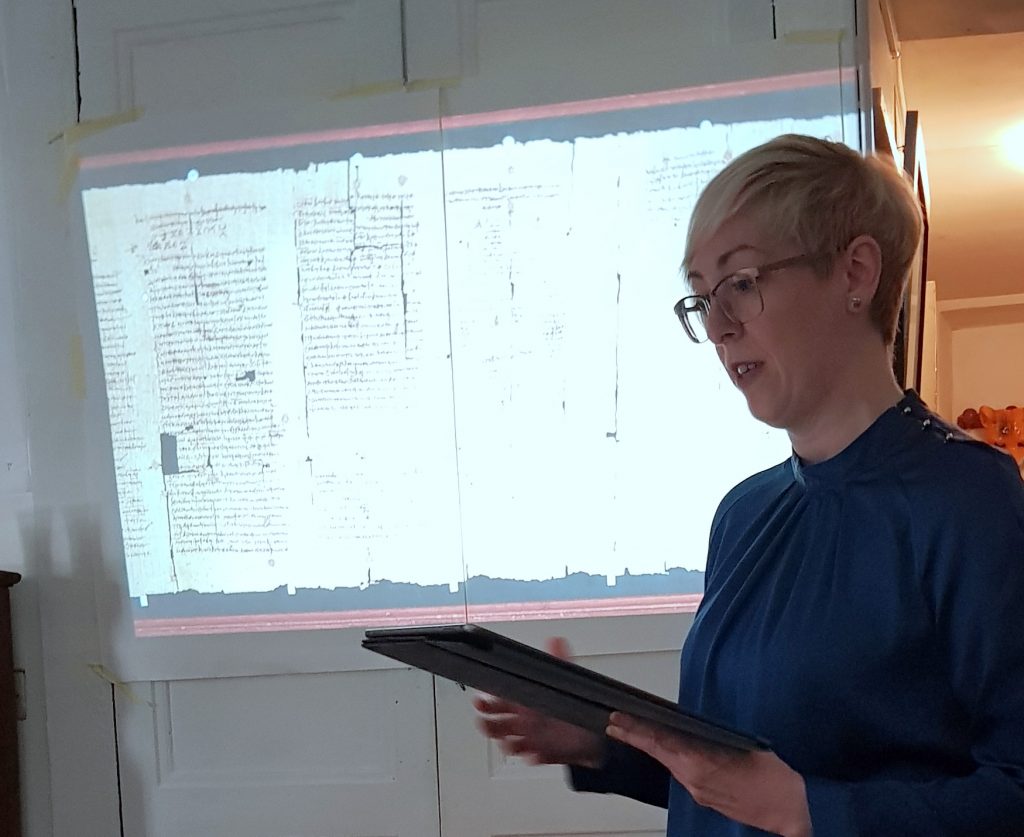

Image by Sally Annett.

We were first contacted by the curator of Atelier Mélusine, Sally Annett, in December, and in collaboration with her we developed an exhibition that would allow the magical papyri to be experienced in new ways – visually, as art works, audio-visually, as sound and video installations, and practically, in a workshop in which we invited the audience to recreate them. The fact that the manuscripts we study are scattered around the world, and too valuable to easily transport, meant that we could not have an exhibition of the manuscripts themselves. Instead, we developed the idea of using tracings of the images from them. In the process of our research, we were already producing digital tracings of the images in the magical papyri. Our reasons for this are quite practical – we include them in our database, we use them in publications, and the process of tracing the images helps us to better understand their content and how they were produced. Magical images are certainly not a form of high art – they were produced for practical purposes, and usually, it seems, by people with very little training. People often say that they often look like children’s scribbles, and their iconography can be very hard to understand. Nonetheless, they are a very important part of our research, and we felt that presenting them in a gallery as artworks rather than as parts of textual editions would allow them to be experienced in a new way.

One of the key researchers leading the way in understanding magical images is Raquel Martín Hernández of the Complutense University of Madrid, who has been running a project called To Zodion, focusing on images from Greek and Demotic papyri since 2015. We contacted Raquel early on to ask if she would like to participate, and we were very happy when she agreed. Together, we selected 27 images from papyri dating from between the third and eleventh centuries, from Demotic, Greek, and magical texts, containing dozens of images of gods, angels and demons. Each of these images was reproduced at their original size, so that, even though they were printed on modern paper rather than papyrus or parchment, the audience would still get a sense of their physical presence, the thickness of the pen lines drawn by the scribes who produced them, with every wobble and correction preserved as in the original.

Video by Raquel Martín Hernández.

The Atelier Mélusine is built into the remains of a medieval castle, and has several unusual spaces; one of them is the “crypt”, a small room with the living rock on which the castle is built as one of its walls. Together with Sally and Raquel, we developed the idea of using it to project the images, giving another sense of the divine beings they portray at a superhuman scale, drawn in light. We had the good fortune to collaborate with Luis Calero of the Universidad internacional de La Rioja, an expert in ancient Greek music and a very talented performer in his own right. He produced two musical pieces to accompany the visuals for the crypt – a sinister, severe reconstruction of the Hymn to Typhon, a Greek text from the fourth-century Great Magical Papyrus of Paris (PGM IV), which calls upon the god Seth-Typhon for help. This was accompanied by images from the Greek and Demotic papyri, which often depict this god torturing the human victims of spells. To go with the images of angels and other divine beings from the Coptic texts, Luis provided a reconstruction of the Oxyrhynchus Hymn, the oldest piece of Christian music for which the notation survives, preserved on a papyrus fragment from third century Oxyrhynchus.

Image by Sally Annett.

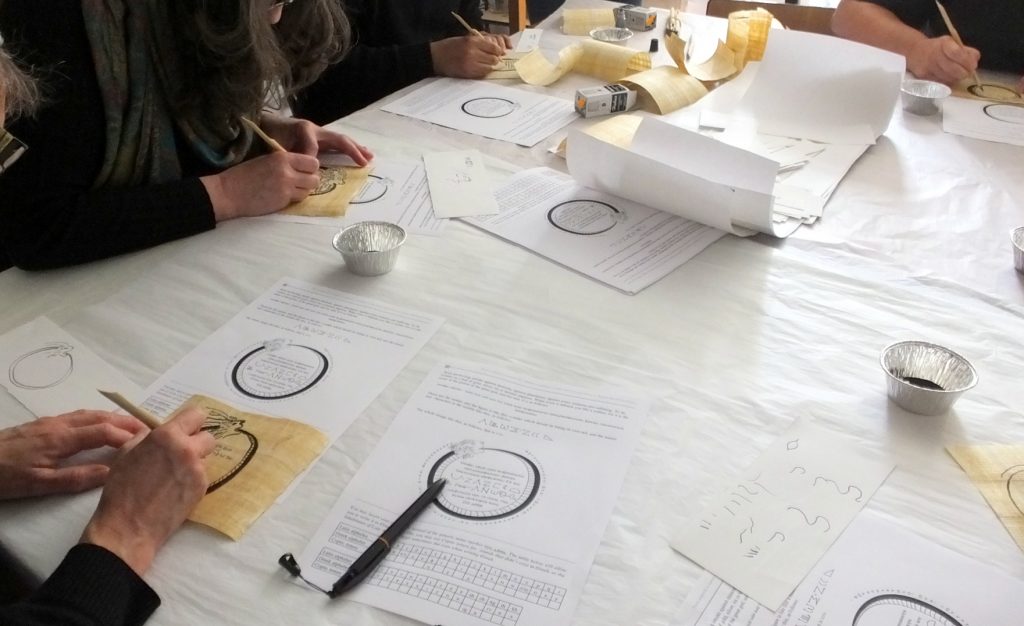

On Sunday 12th May, we held a lecture and workshop. The lecture, presented by Raquel Martín Hernández and Korshi Dosoo, explored the history and origin of the magical texts, while the workshop involved the creation of a magical amulet, using the body-protecting amulet (phulaktērion sōmatophulax) from the fourth-century PGM VII (P.Lond. I 121) as a model. This text, consisting of a lion-headed ouroboros, kharaktēres, magical words, and a short formula, contains many of the typical features of a magical text, including space to insert your name, and so offered a perfect model.

Image by Sally Annett.

The workshop participants used pens based on ancient Greek reed pens, or kalamoi, to write on papyrus, working from a translated set of instructions from the original handbook. While this was an enjoyable activity, it also served as an example of experimental archaeology – the process of copying a text in a similar way to an ancient scribe allows us to appreciate material and experiential aspects that are absent when we simply try to imagine rituals. These can be very basic – the problems that we had controlling the ink flow demonstrates that experienced scribes had to learn how to write fluidly without leaving spots of ink and illegible letters after refilling their kalamoi. But the process also helped us to explore the ways in which magical texts might be transmitted and change over time – none of the amulets we produced were the same. Each participant miscopied some text, or ran out of space and had to change their approach, or added or reinterpreted elements. We see very similar processes at work in the magical manuscripts we study, in which even closely related texts show divergences which are often quite significant. The participants in our workshop even did some unexpected things, like trying to trace the image through the papyrus – something that would probably have been even easier to do with the higher quality papyrus which would often have been used in the past.

Image by Sally Annett.

Alongside the work produced by our team and Raquel, Sally presented work from the artist Robert Campbell Henderson, born in Scotland but a longtime resident of France. This work was a fascinating mix of print, photography, sculpture and audio-visual installation, which shared with our work the themes of the relationship between humans and the supernatural, and the recreation of images across time and space. The first body of work is a series of re-prints of the work of the French artist Serge Arnoux, whose copper plate etchings of William Blake’s Proverbs of Hell had been lost until Robert found them in 2018 in a scrapyard. These strange, mystically-inspired black-and-white prints provide an excellent parallel to the prints of the magical images, as does the second body of work, Blash o’God, a collaboration with the poet Hugh McMillan exploring the life and death of the 18th-century prophetess Elspeth Buchan. Together, the work produced by our team and Robert Campbell Henderson traces two thousand years of human attempts to understand, describe, and depict the divine realm, and our own reflections on these attempts.

The exhibition Tracés temporels et manuscrits magiques will run until the 29th June, and we hope to be able to display and develop this way of presenting our work at other locations in the future.