With conference season still in full swing, last week saw the seventh biannual conference of ESSWE – the European Society for the Study of Western Esotericism – in Amsterdam. This was an incredibly diverse conference, with papers on fields ranging from Christian Kabbalah to spiritual cinema, and from the anthropology of modern New Age practices to the second sight in Victorian Scotland. Over a hundred talks in all, they were bound together by a set of common themes – consciousness, altered states, and extraordinary experiences.

Here we will only be able to summarise very briefly the papers which discussed topics related to the ancient Mediterranean, but for those who would like to learn more we encourage you to check out the online programme and list of abstracts, which will help you find out more about the speakers and their fascinating topics. The conference also coincided with a beautiful exhibition on the history and modern reception of Jewish mysticism, which will run until the 25 August 2019 at the Jewish Historical Museum and a few other locations in Amsterdam.

One of the keynote speakers was Yulia Ustinova (Ben-Gurion University of the Negev), an expert in ancient Greek religion, whose approach, combining the study of texts and images, and using the techniques of anthropology and cognitive neuroscience, allows her to dig into literary sources to more deeply understand the religious experiences of ancient Greeks. Her paper focused on epipnoia – “inspiration”, also described as enthousiasmos or “engoddedness” – being filled with a god. According to Plato, this inspiration came in four forms – poetic, the gift of creativity given by the Muses; mantic, the gift of foresight given by the god Apollo; telestic, the ritual frenzy associated with Dionysus; and erotic, the experience of intense love caused by Eros. Ustinova described the use of a process she calls “cabling” – combining different strands of evidence, ancient and modern, so that the deficiencies of one source are made up for by another – to look at how we might understand the phenomenological and embodied experience of altered states of consciousness in ancient Greece.

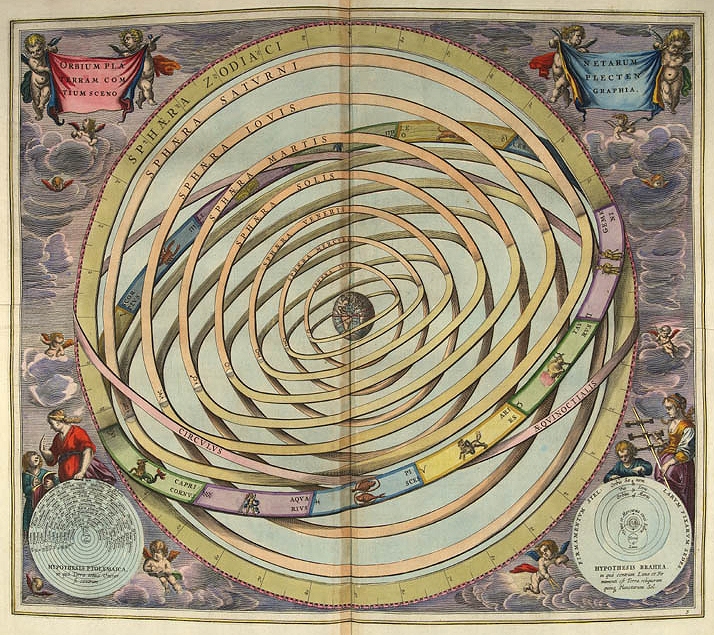

Nicholas Banner (Trinity College Dublin) presented a paper on “cosmic ascent” in Platonist texts from the first through third centuries CE. Banner described how cosmic ascent – the act of rising into the air and visiting the heavens – seems to have replaced the descent, or katabasis, as the key mystical experience in Greek philosophy and religion after the time of Plato, and divided it into two forms. The first is the interior ascent, described by Diotima in Plato’s Republic, and found in the writings of the Church Father Augustine, in which the ascent is primarily mental, while the second, the cosmic, or even hypercosmic ascent, is based on the cosmology of Plato’s Timaeus and a literal reading of the ascent-myth in the Phaedrus, and describes an actual ascent, in which the body rises from the earth into the heavens. Banner identified two first-person descriptions of ascent from the Roman period – the first by the Jewish Alexandrian philosopher Philo, and the second by Plotinus, the founder of the movement called “Neoplatonism” by modern scholars. From the examination of these and other texts, Banner proposed a three-part model of the universe which these visionaries shared – the flawed sublunar earth from which they rose, the perfect cosmos, made up of the planets and stars through which they ascended, and the hypercosmic realm beyond the stars, the source of divinity for which they aimed. Banner suggested that an examination of the typical topoi, or tropes, of these ascent narratives, could allow us to identify unexpected elements in particular first-person accounts. Plotinus, in particular, seems to describe ascent in an unexpected way, which may be a result of his own real mystical experiences.

Christian H. Bull (University of Oslo) presented the first of several papers on the Hermetica, the collection of Greek texts describing the teachings of Hermes Trismegistos, the Greek name for the Egyptian Thoth. These texts probably date from the first few centuries CE, but claim to be far older. Bull’s paper, presenting material more fully elaborated in his recent book, used the corpus to reconstruct the process by which an individual would be initiated into a Hermetic group, and through a series of rituals and mystical experiences achieve spiritual perfection and encounter the divine. The first text in this sequence is the Poimandres, which describes how Hermes was visited by the divine emissary Poimandres, and united with him, understanding the true nature of the universe and becoming the guide and saviour of humankind. Bull suggested that the author may have based this account on something that he himself had experienced, and that this myth would serve as both a charter for Hermetic practice, and as a description of the divine encounter at which initiates could aim. The Hermetic “path of immortality” would continue with the study of the other Hermetic texts, combined with spiritual exercises designed to make the initiate aware of the illusory and imperfect nature of reality, in which the soul was bound by the force of fate, mediated by the stars. The culmination of the process in Bull’s model was a ritual, described in Corpus Hermeticum XIII, in which the demons who inhabited the body would be cast out by divine powers, and the initiate would be reborn. Newly divinised, the initiate could then experience the world as good, and go on to experience the godhood in its fullness, undergoing a mystical ascent described in the Discourse on the Eighth and Ninth. Bull’s approach focuses on the ritual and experiential aspects of the Hermetica, often ignored in studies which treat them solely as literary texts, as well as on resolving the problem of the contradictory approach in the Hermetica to the material world – sometimes described as bad, sometimes good – by suggesting that the initially negative approach to the world would change to a positive orientation once the initiate had been reborn, an approach he calls pedagogical dualism.

Three papers, not part of same the Late Antique panels as the others, also dealt with themes of the Hermetica, and the related concept of Gnosticism. Anna van den Kerchove’s (Institut protestant de Théologie) paper explored the relationship between the concepts of “truth” and “knowledge” in the Hermetica, comparing it to that within Platonic philosophy. She suggested that the supreme knowledge discussed in the Hermetica existed on a spectrum with normal knowledge, and that the processes they described aimed at the creation of a specific type of human being through ritual practices. April DeConick (Rice University), long a recognised expert on ancient Gnosticism, suggested a sociological approach to the controversial religious movement. While most accounts of Gnosticism focus on their idea that the world is the creation of an evil Demiurge, DeConick suggested that we should instead understand the Gnostics as being focused on a transcendent supreme God, separate from the Biblical God, and known through a direct, “Gnostic” experience. She described how this could be the result of a Gnostic life event, which might happen to those who found themselves dislocated from their society, culture and religion, and sought metaphysical truths. She suggested that these incidental gnostics – whose experience of gnosis was through a direct event – could be contrasted to historic gnostics, who encountered Gnosticism through texts. The third paper in this session, by Wouter Hanegraaff (University of Amsterdam), looked at ancient Hermetism through the lens of the problem of translation – the fact that all experience can only be communicated through language, and that every attempt to understand language is an act of translation from one mind to another, subjective and imperfect. This problem of translation is apparent in the Greek word nous, often translated into English as “mind” or “consciousness”, but located in the heart rather than the brain by ancient writers, and understood in the Hermetica as a sensory organ which allowed one to perceive spiritual objects. Perception by the nous in the Hermetica is direct, bypassing the problem of translation through a mystical experience of shared identity, which modern psychology may in part help us to understand.

The final paper on the Hermetica, by Yang Gao (Northwest University) took a different approach, looking at the series of the first thirteen treatises in the canonical collection as an anodos, or way of ascent, beginning with the diagnosis of the problem of human existence in the Poimandres and continuing with a discussion of the nature of the universe and the tension between good and evil in the world. Gao suggested that the Hermetica should be understood as resolving the problem of good and evil in the cosmos by describing the universe as inherently good, as a creation of the divine, but imperfect, since it must be subject to passion and motion, a contradiction inherent in all existing things. This tension would be experienced in a shifting fashion by the initiate as he progressed, with his valuation of the world changing from positive to negative and back to positive as his awareness of it expanded, finally understanding it as both good and beautiful. The ability to understand and experience it as good would be brought about, as in Bull’s scheme, by a ritual deification, which he locates in Corpus Hermeticum XII. This paper, then, both argued that the traditional order preserved in manuscripts is meaningful, and that the tension between the positive and negative aspects of the universe they describe is not between two perspectives, but a single perspective which changes along with the initiate’s knowledge.

Two papers looked at late antique Jewish texts, and the mystical experiences they described – the speakers – Rebecca Lesses (Ithaca College) and Naomi Janowitz (University of California-Davis) have published extensively on this rich and complex topic, and those interested in learning more are encouraged to consult their publications. Lesses’ paper provided an introduction and analysis of the Hekhalot (“palaces”) literature, which survives in medieval copies of much older texts, and dates originally to between the fourth and seventh centuries CE. These texts describe ritual practices which allow the user to ascend through the heavens to the palaces of the angels, and ultimately of God himself, and view his throne, gaining superhuman powers in the process. Full of intricate theology and ritual, these texts challenge modern categories of literature and practice, and of magic and mysticism. The practices concretely consist in reciting a series of hymns, the same hymns used by the angels who are present before God, learned by Rabbi Akiva, one of the major figures of early Rabbinic Judaism. The texts also claim that only a certain type of man can perform these rituals – someone both ritually pure and morally upright and obedient to the Jewish laws. Lesses suggested that while the distance between ourselves and the texts, and the texts and their authors, is too great to allow us to easily reconstruct the psychology of the practitioners, they nonetheless describe numerous physical features of these heavenly experiences which lend them a certain concreteness. At the various palaces along the ascent, for example, the ritualist had to show the angelic guardians seals held in their hands, and he would be physically carried by the angels to the next palace.

Janowitz’s paper took a different approach, looking at how disputes among modern historians about the meaning of ancient mystical texts may be the result of conflicting underlying assumptions about the use and function of language. Janowitz began with the example of a fifteenth-century painting which includes a blue object: a modern onlooker might understand it as simply representing an object which was blue, whereas a contemporary viewer would know how expensive blue paint was, and understand that the painter must therefore have a rich patron. Drawing on Charles Peirce’s theory of signs, she described these two approaches as rhematic – seeing things as directly representational – and indexical – pointing to other things beyond themselves. The use of indexical signs in particular, she suggests, leads to a process called “dicentization”, in which signs can be understood as having a physical connection to the object which they represent. In practical terms, this can be used in texts to create links between different aspects of reality. In the Songs of the Sabbath Sacrifice, a ritual text from Qumran, for example, the heavenly world is described using terminology usually used for the human, and specifically priestly, realm, linking together the two so that priests can be understood as almost divine, and the divine realm becomes priestly. Likewise, in the Hekhalot texts, such as the Maaseh Merkabah, the experience of the divine realm is recounted through a series of speakers, each of which reports another, creating a chain of authority which lies behind and supports the text. This approach – seeing the text itself as acting through its use of dicentization – allows us to avoid problems of phenomenology or efficacy in ritual texts.

Two papers focused on the Greek and Demotic magical papyri, and their “rituals of apparition” – spells used to summon gods to appear in order to answer questions. Korshi Dosoo (University of Würzburg) focused on an example from the London-Leiden Demotic magical papyrus (PDM xiv, 3rd century CE), in which Anubis is summoned into a bowl of oil, where he entertains a group of gods in a party which ends with one of them volunteering to answer questions for the ritualist. This scene is described in a conversation between the practitioner and a boy who serves as a medium, looking into the bowl and describing what he sees. While the description has a literary quality, Dosoo demonstrated that very similar accounts of real rituals are described by later first person accounts, from John Dee (1527-1608/9 CE), a philosopher and magician from Elizabethan England, and Edward Lane (1801-1876), a Victorian visitor to Egypt. Dosoo’s paper explored different possible approaches to this text – the ritual resembles hypnosis, and the descriptions of the use of boy mediums in the papyri even suggest that their users were aware of the variability of responsiveness to hypnosis, a feature well-known to modern psychologists. But, drawing on recent work by Egil Asprem, Dosoo suggested that a purely psychological reading was insufficient, and could be extended by looking at the way in which language itself could be used to construct the experience of encountering the divine. As in a modern role-playing game, the magician and medium would jointly describe and interact with a scene created through spoken words.

The second paper on the magical papyri, by Andrea Franchetto (University of Amsterdam), looked at a ritual from the Great Magical Papyrus of Paris (PGM IV, 4th century CE), in which a single ritualist summons a god into the flame of a lamp. Franchetto’s analysis combined the work of Asprem with spatial and body-focused approaches to religion to investigate the sensory and physical aspects of the magical practices. In his paper, he demonstrated the way in which the ritual space was a “cognitive artefact” – created by arranging objects – a lamp, papyrus cords, a sprig of wormwood – in a significant way, which allowed the physical space to blend with a preconceived mental space. Through a cognitive process called predictive coding, “prior probabilities” – expectations about the sensory experiences that the ritual should evoke – would combine with the stream of incoming sensory data, to create an experience of interacting with “intermediary beings” – in this case the solar god who appears in the lamp. Franchetto’s paper ended with the question of how cognitive neuroscience could be combined with philology, a question to which his own paper suggested some possible answers.

Paul Pasquesi’s (Marquette University/Cardinal Stritch University ) paper dealt with texts describing the extreme practices and experiences of Syrian Christian ascetics from the fourth to eighth centuries CE. Looking at modern understandings of the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, he described how wearing oneself down through extreme exertion, exposure to the elements, and sleep and food deprivation could make one more susceptible to extraordinary experiences, and demonstrated that these are exactly the kinds of practices found among the Syriac ascetics. These individuals might live in remote mountains, in tombs, or in caves, and would fast and pray constantly, shunning sleep and avoiding human contact for decades at a time. These practices resulted in extraordinary visionary experiences – authors who write about them, such as the historian Theodoret (died after 452 CE) describe ascetics as conversing constantly with God, while the ascetics themselves provided written accounts of their visions. Once such account, the Homilies of Macarius-Symeon (mid to late 4th century CE) describe how constant prayer and exhaustion of the body would allow the Holy Spirit to fill the heart with divine fire, resulting in an experience of theosis, or deification, becoming like God.

In this blog we often deal with the important, but very basic problems of interpreting and understanding texts. The papers discussed here, though, offer a different perspective on the study of ancient religion – incredibly complex, both in the material they cover and in their theoretical approaches. The presentations suggest ways in which we might go beyond the written word to explore the extraordinary experiences and philosophical assumptions contained in ancient texts.

For more on the ESSWE conference, you can read the thoughts of Earl Fontainelle, the host of the Secret History of Western Esotericism podcast, and another conference attendee, here.

*I would like to thank Nicholas Banner, Christian Bull, Andrea Franchetti, and Paul Pasquesi for offering comments and corrections to a draft version of this post. Any mistakes which remain are my own.

One Comment

Pingback: