This week’s post takes another deep dive into one example of a curse from Kyprianos, our database of Coptic magical texts. Chicago, Oriental Institute Museum E13767 is a sheet of paper cut into a rectangle that measures 6cm in height by 16 in width. One horizontal crease suggests that it was folded vertically only once, while 15 vertical creases suggest it was folded multiple times, or rolled and squashed into a small package of only about 3cm in height and 1cm in width. Bought from a private collection for the Oriental Institute Museum in 1929, it is unfortunately unknown where the manuscript was found. The handwriting of this text suggests a relatively late date, approximately between the 9th and 11th centuries CE.

First published in English by Elizabeth Stefanski in 1939, a translation of this curse appeared more recently in the collection of translations of Coptic Texts of Ritual Power by Marvin Meyer and Richard Smith, where it was translated by Marvin Meyer, as well as online at papyri.info by Terry Wilfong. A translation into Italian is also provided by Sergio Pernigotti in his compilation “La magia copta: I testi”.

Another example of an activated text, this manuscript is testament to a magical practice that was used to strike a man called Pharaouō down with impotence. The evidence of folding suggests that the inscribed activated curse might have been deposited near the targeted man, perhaps under his doorstep or at a crossroads where he was expected to pass by, or else with a corpse in a tomb.

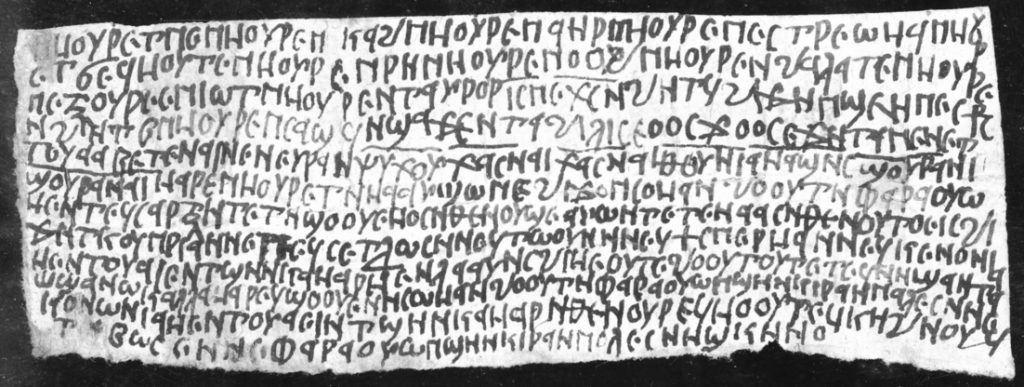

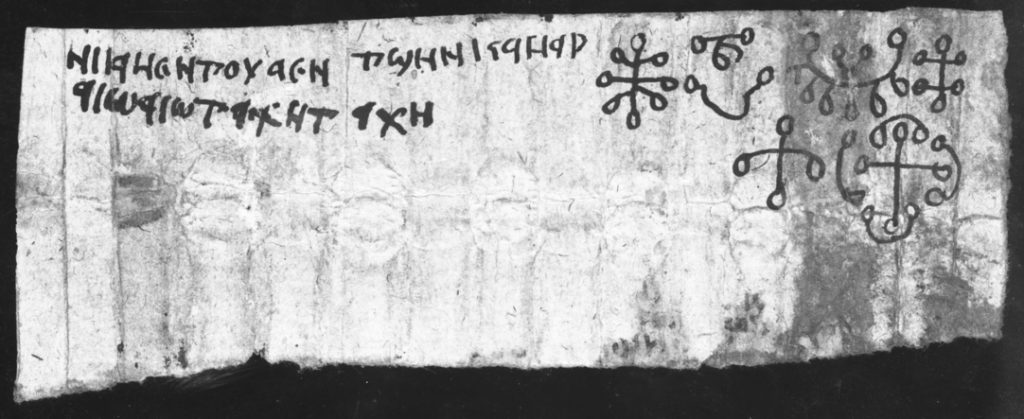

The front (recto) of this sheet of paper is inscribed in 12 neatly-written lines which preserve the majority of the invocations and commands of the ritual practice. The back (verso) finishes this composition with two lines of text, followed by seven kharaktēres (characters) formed as ring signs. Distinctive among these is the eight-pointed star, as well as an iconographic form comprised of a cross surrounded by four bowed lines, all of which have rings at the end of their lines.

O binding of the sky, O binding of the earth, O binding of the air, O binding of the Firmament, O binding of the Pleiades, O binding of the sun, O binding of the moon, O binding of the birds, O binding of the ring of the Father, O binding with which Jesus Christ was crucified (?) upon the wood of the Cross, O binding of the seven words which Elisha spoke upon the head of the Saints, whose names are: Psukhou, Khasnai, Khasna, Ithouni, Anashns, Sourani, Souranai!

May that binding be upon the male member of Pharaouō and his flesh so that you (pl.) dry it like wood and you (pl.) make it like a rag upon the dung heap! His penis will not become hard! He will not become erect! He will not ejaculate! He will not have sex with Touaein, the daughter of Kamar, nor any woman, man or animal until I recite, myself (a spell?)! But have the male member of Pharaouō, the son of Kiranpales, dry up! He will not have sex with Touaein, the daughter of Kamar, like a corpse lying in a tomb, while Pharaouō, the son of Kiranpoles, will not be able to have sex with Touaein, the daughter of Kamar! Yea, Yea! Quickly, Quickly!

Chicago, Oriental Institute Museum E13767 Recto lines 1-12 to Verso lines 1-2

Following an invocation to all parts of Creation, from the sky to the earth, sun to the moon, and even by the binding which held Jesus upon the Cross, as well as the seven names which Elisha is supposed to have spoken over the saints, the outcome of the recipe becomes clear. This practice is to strike a man, named Pharaouō, and his “male member”, his sexual potency. As many of these elements of the natural and supernatural world are to be bound, so too must his phallus become ‘dry like wood’ and like ‘a rag upon a dung heap’. Pharaouō will no longer be able to get an erection, nor ejaculate, becoming impotent in both senses of the word, and so he will be prevented from having sexual intercourse with Touaein.

There are several ways to interpret and contextualize this binding spell. In our project, we interpret these particular mechanics as ways in which parents aimed to protect their daughters from either losing their virginity, or it becoming known that they had. In the context of Byzantine and Islamic Egypt, the importance that a bride would be virginal is paramount, and extramarital relationships threatened the viability of finding a husband for a woman.

Although this curse could also be interpreted as one commissioned by a jealous man, perhaps besotted with Touaein, and thus desperately jealous that she was instead in a relationship with Pharaouō, in such cases we find instead curses that bind the woman, not the man. Such curses would insist that the woman not have sex with any other, and that she would become submissive to the named man – the one responsible for commissioning the practice.

Conceivable, then, is that a parent of Touaein is trying to protect her reputation and social status, but by doing so are also seeking to punish Pharaouō, perhaps their daughter’s boyfriend or suitor, for his transgressions. The curse commands that not only that he will be unable to have sex with Touaein due to his impotency, but that he will be unable to have sex with any other “woman, man, or beast” until “I” – the parent or the practitioner – “recite”, i.e. say so! Pharaouō’s sexual virility is to be reduced to that of “a dead man”, a corpse, “lying in a tomb”, flaccid, limp, and impotent.

This is one of now more than 30 Coptic curses that are entered and edited in Kyprianos, our database of Coptic magical texts. The majority of these curses are “activated”, and so shed exclusive – and, as we have seen, intimate – light onto social situations experienced by real people centuries ago. As we continue the process of editing and (re)discovering these stories, we will aim to continue to share them with you in this, and other, series of posts in the coming months.

Bibliography

Meyer, Marvin W., and Richard Smith. Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts of Ritual Power. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press, 1999, no. 85, pp. 178-179.

Pernigotti, Sergio. “La magia copta: I testi.” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt, edited by Hildegard Temporini and Wolfgang Haase, II.18.5, pp. 3685-3730. Berlin and New York: Walter de Gruyter, 1995, no. 28, p. 3723.

Stefanski, Elizabeth. “A Coptic Magical Text.” The American Journal of Semitic Languages no. 56 (1939): 305–307.

One Comment

Pingback: