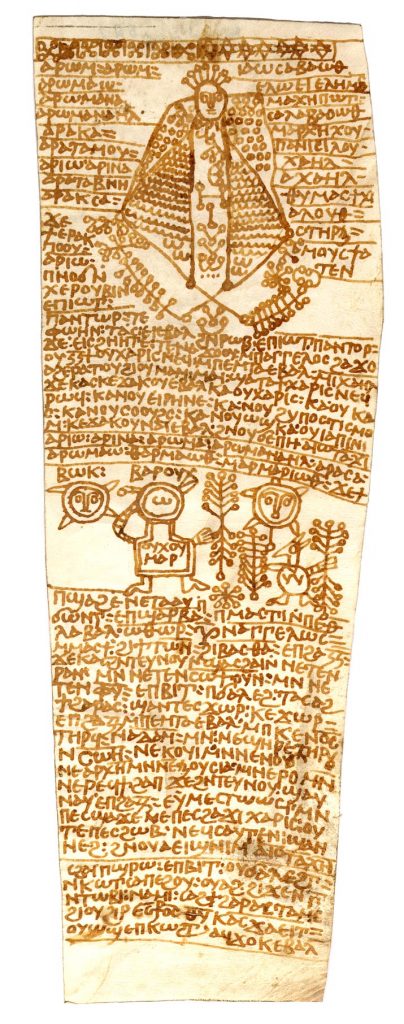

This week’s post takes a deep dive into a curse from Kyprianos, our database of Coptic magical texts, by returning to a manuscript already discussed in a previous post: P. Heidelberg inv. Kopt. 681 is a sheet of parchment, cut into a long rectangle measuring 29.5cm by 10.9cm. As introduced in the post Coptic Amulets II: Sending an angel to give grace, this sheet is a formulary – a manuscript containing one or more spell(s) with formulas to be filled in, rather than an activated text – containing the name of the person who would benefit from, or be cursed by, the spell.

The flesh side of the parchment, the inward-facing side of the skin, is inscribed with 52 lines, the first 27 of which are a spell which command a cherub, a type of angel, to bring favour – the subject of the previous post about this manuscript. The remaining lines of the parchment, the subject of this post, contain a spell for the quite the opposite purpose – a curse. This manuscript, dating to the second half of the 10th century CE, is one of nine manuscripts which Iain Gardner and Jay Johnston (2019) have demonstrated belong to a collection of related texts – “the Heidelberg Magical Archive” – and one of six written by the same scribe, who identifies himself in one of them as the Deacon Iohannes. This is therefore one of the very rare cases where we know the name (and even job title) of someone who copied a magical text. A translation of this healing amulet into German was first produced by Friedrich Bilabel and Adolf Grohmann in their publication of many of the magical manuscripts from the Heidelberg Papyrus Collection, and a translation into English appeared more recently in the collection of translations of Coptic Texts of Ritual Power by Marvin Meyer and Richard Smith, where it was translated by David Frankfurter.

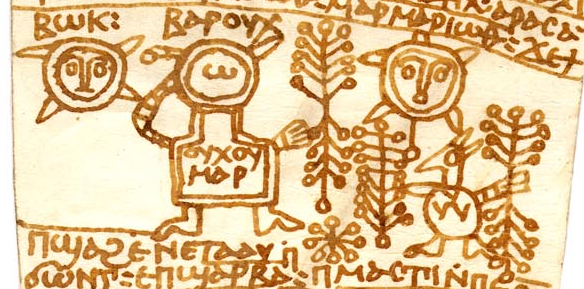

A series of figures precedes the text of the curse itself; four figures are depicted. The first, seemingly in the form of a face, is named Bōk, the second, a full relatively anthropomorphic figure is named Baroukh, and has the letter omega (ō) for a face, and “Oukhoumar” written upon its body. A second face-like form is depicted, without a name, above a fourth figure with an avian, canid, or equid head. The figure named Baroukh holds its right hand to its face, and a palm staff in its left hand. Similarly, the animal-headed figure holds one such staff in each hand. As we will see, the curse itself mentions the face of the target on several occasions, perhaps, then, these faces related to those targeted. At the centre of the base of this series of figures sits an eight-pointed star – a common kharaktēr, or symbol, found in magical texts.

Underneath a register line diving this series of figure from the text, the invocation begins:

“Give the flame of those who made them(selves), the wrath of the scorching heat, the hatred of the shattering, Othōr, 400 angels of hatred and strife and hatred, to the face (of) so-and-so, so that in the moment when I write your (pl.) names and your (pl.) figures and your (pl.) amulets on the edge (of) the pot, (and) I kindle under it until it shatters, you will shatter the face (of) so-and-so in the presence of the entire race of Adam and all the children of Zoē: the small and the great, the rulers and the authorities and (the) kings and the judges, so that in the moment when they see the face (of) so-and-so, they will hate it and her speech. Her face will not receive grace, and her work will not be upright for ever, at any time! Yea! Quickly!”

P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 681 lines 27-47

In this invocation we see that manifestations of “flame”, “heat”, and other destructive forces such as “shattering” are invoked alongside 400 angels – here invoked as a malign force, who will bring “hatred” and “strife” upon the face of the targeted person. The text contains to prescribe that as soon as the practitioner has written the names of those invoked, their figures, and their “amulets” on a potsherd and set a fire underneath that potsherd so that it cracks – “shatters” – under the heat, so too will these beings “shatter” the face of the targeted person. From this ritual instruction, we see that the series of figures and their names that were described above are to be copied onto such a potsherd before being heated over a fire – providing further resonance to the invocation of the “flame” and “heat” invoked at the beginning of the spell.

But not only will the face of the targeted person receive such heat and hatred, but such will manifest in the presence of all humanity – “the entire race of Adam and the children of Zoe”, whether young or old, rulers or divine authorities, kings or judges. The invocation continues to curse the face of the targeted individual, stressing that as soon as anyone sees their face, they will hate it, and in particular they will hate its speech – implying that they will not believe what that person says.

An important point is that the default target of this spell is a woman. Although we have good evidence that all spells could be converted to target men and women alike, the feminine pronouns used in the text make it clear that this particular formulary prepared a spell to curse the “face” of a woman. This is why we see mention not only of “the face” but “her speech”, “her face”, “her work” – all of which will be hated and unsuccessful “for ever at any time”, that is, indefinitely. In the introduction to the earlier English translation of this curse, the editors suggested the “face” of the woman referred to her beauty, which may have had “importance”, but a broader comparison with the concept of the “face” in Coptic magic suggests it refers to something closer to the “social face” – the part of oneself that interacts with others, including one’s charisma or personal charm.

After a section break, the series of ritual instructions to be followed are inscribed.

“Write (in) menstrual blood on the edge (of) a pot. Lay it on its back. Place (it) upon three mudbricks. Kindle under it. Bury (it) at a cross-roads. Offering: olive pit. Consume (with) the fire. It is complete.”

P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 681 lines 48-52

The potsherd that appears in the invocation discussed above now appears again in these ritual instructions. The names, figures, and amulets described above are not to be inscribed upon the potsherd with ink, but with menstrual blood – a substance commonly found in such malign ritual practices. This potsherd is then to be placed upon three mudbricks with the fire set underneath it. This will bring about the outcome specified in the invocation discussed above, that the potsherd will “shatter”, just as the face of the targeted person will. Those sherds are then to be buried at a crossroads – perhaps one where the targeted person is expected to pass by, while the offering that is to accompany the ritual practice is the burning of an olive pit.

As the first spell from this parchment sheet, this curse provides further evidence of a formulary that would have been used as a ‘master copy’ by a practitioner of Coptic magic. From this formulary, the practitioner, who was likely the same as the Deacon Iohannes identified by Gardner and Johnston as the scribe who wrote several other manuscripts of “the Heidelberg Magical Archive”, would have been able to copy the names, figures, and amulets, onto the potsherd which then would have been burned until it cracked, and buried under the crossroads. In the recitation of the spell, the practitioner would then have had the name of the client inserted where this spell says “so-and-so”, perhaps to ensure that when/if she passed by the crossroads, she was targeted by the beings invoked in the curse. It’s interesting to note that the Heidelberg collection shows that Iohannes was interested in all kinds of different practices – this single sheet alone shows that he might equally carry out rituals to give favour, and to destroy someone socially.

As we continue the process of editing and (re)discovering such curses, we will aim to continue to share them with you in this, and other, series of posts in the coming months.

Bibliography

Bilabel, Friedrich, and Adolf Grohmann. Griechische, koptische und arabische Texte zur Religion und religiösen Literatur in Ägyptens Spätzeit. Heidelberg: Verlag der Universitätsbibliothek, 1934.

Gardner, Iain and Jay Johnston. “‘I, Deacon Iohannes, Servant Of Michael’: A New Look at P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 682 and a Possible Context for the Heidelberg Magical Archive”. Journal of Coptic Studies 21 (2019) 51-53. URL

Meyer, Marvin W., and Richard Smith. Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts of Ritual Power. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press, 1999.