In this new series of blog posts, we will be looking at the place of animals in Coptic magic, beginning with an introduction to the different roles that they play, and ending with a discussion of one strange substance. This series summarises and updates an article written by Korshi Dosoo, Suffering Doe and Sleeping Serpent: Animals in Christian Magical Texts from Late Roman and Early Islamic Egypt, which is available to read online in open access.

It is well known that ancient Egyptians often represented their gods in animal, or part-animal forms, reflecting the idea that the animal form, like the human form, was potentially divine. This idea continues in the Graeco-Egyptian magical papyri written in Greek and Coptic between the first century BCE and fourth century CE, in which Egyptian, and sometimes even Greek, gods might be invoked by describing their animal forms – the ibis or baboon forms of Thoth-Hermes, for example – or by offering them substances which were linked to their sacred animals – the blood and fat of a dove offered to Aphrodite.

This changed with the massive cultural shift to Christianity which took place in Egypt in the fourth and fifth centuries, and which marginalised animals within the sphere of religion. To give one example, the important ritual of animal sacrifice was replaced by the sacrifice of Jesus, God in human form, which was commemorated in the animal-free communion ritual. This same change is reflected in magical practice, in which animals become much less central. But they do not completely disappear from Christian magical practice. We can identify five ways that animals appear in Coptic magical texts from Egypt, which we will discuss in this series:

- Divine animals: The rarest role, in which animals retain some part of their pre-Christian superhuman status.

- Dangerous Animals: Creatures, like snakes and scorpions, which posed a threat to human life, and which could be magically repelled, or called upon to attack human enemies.

- Endangered Animals: Animals with an important role in human life, like horses, cattle, and pigeons, which had to be magically protected from natural and supernatural threats, or which could be targeted to harm rivals.

- Symbolic animals: Animals whose typical behaviour could be evoked in rich metaphors.

- Animals used for materia (magical materials): Animals whose bodies, or parts of them, could be used in magical rituals.

We will look at one example of this last role here.

In many Coptic magical rituals with a broadly “positive” purpose we see the use of the “blood of a white dove” (Coptic snof n-ou-crompe n-leukon), usually as a kind of ink:

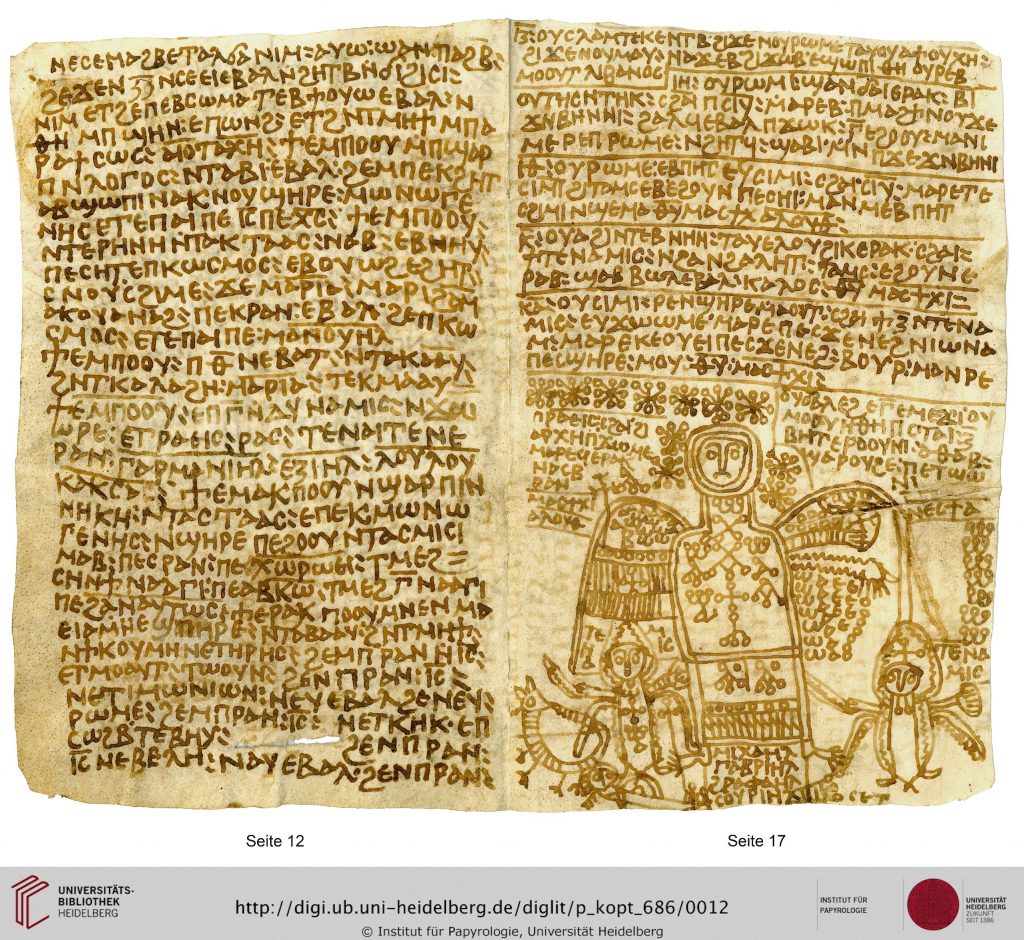

⟨A⟩ favour ⟨procedure⟩. Draw this image with ⟨the⟩ blood ⟨of a⟩ white dove. Bind it upon yourself. Offering: musk.

(PCM I 26 p. 15 ll. 32-33 (X CE):)

This example is for favour – general good luck and social success – but we find similar rituals in love spells, rituals to acquire a good singing voice, to attract customers to a shop, to find treasure, and so on. All of these suggest that the blood of this bird was believed to have a positive, attractive quality which it would impart to the objects upon which it was applied.

If we think about the cultural associations of white doves, the reasons for this are quite clear. “Whiteness” had a positive connotation, associated with purity and light, and, as we have already seen, doves were associated in Greek culture with Aphrodite, the goddess of love. Within Judaism and Christianity, the dove also had erotic connotations; in the Song of Songs the beloved woman is called “my companion, my beautiful dove” (2.10), “my good dove” (2.14), and “my perfect dove” (5.2). Less erotic, but still positive, is the association with the Holy Spirit, which came down upon Jesus in the form of a dove at his baptism (Matthew 3.13-17, Mark 1.9-11, Luke 3.21-23, John 1.32), and with the Virgin Mary, often metaphorically described as a dove in Christian literature.

From a practical perspective, acquiring a dove to bleed would also be relatively easy – doves (or pigeons, which are the same bird) could be found everywhere in Late Antique Egypt, as they still can be today; in a future post, we will discuss the many dovecotes, the miniature towers in which pigeons were bred for their droppings, used as fertiliser, and for their meat.

This material also allows us to see the deep continuities in magical practice across time and space. After Egyptian Christians began speaking and writing in Arabic in the second millennium CE, a common type of magical practice involved using the Psalms, and the recipe associated with Psalm 124 is for favour; here is one example from an eighteenth-century manuscript:

The 124th Psalm brings great favour. It is written with the blood of a white dove; one wears it when going before kings, viziers, and others like them.

(Translated after Khater (1970) 173)

But its use was not restricted to Christians; an example from a Jewish handbook from the Cairo Genizah, likely dating to the Fatimid period (X-XII CE), uses the same ingredient in a love spell:

To bring a woman from wher[ever…] at night when the moon is darkened or full take a dove […] kill it and take the parchment made from it and a quill pe[n …] … and with your teeth strike against its heart so that […]

(T-S AS 144.208, 1b:1–411, translation from Saar (2017) p. 130)

As the translator, Ortal-Paz Saar, notes, the ingestion of blood violates the Jewish laws of kashrut, and so it is possible that they borrowed this practice from their Christian neighbours.

But we can find examples from even further afield; in a Greek codex of the sixteenth or seventeenth century, we find the following love spell:

Write with the blood of a white dove on gazelle parchment and approach her; you will be amazed (at the results).

(National Library of Athens Ms. 1265, translated from Delatte (1927) 79.8-9).

We even see a Latin example, copied by a fifteenth-century German practitioner:

When you wish to have the love of whatever woman you wish, whether she is near or far, whether noble or common, on whatever day or night you wish, whether for the furtherance of friendship or to its hindrance, first you must have a totally white dove and a parchment made from a female dog that is in heat, from whom it is most easily to be had. And you should know that this kind of parchment is most powerful for gaining the love of a woman. You should also have a quill from an eagle. In a secret place, take the dove and with your teeth bite into it near the heart, so that the heart comes out, and with the eagle’s quill write on the parchment with the blood the name of her whom you wish, and draw the image of a naked woman as best you can, saying: “I draw so-and-so, N, daughter of so-and-so, whom I wish to have, in the name of these six hot spirits, namely Tubal, Satan, Reuces, Cupido, Afalion, Duliatus, that she may love me above all others living in this world”.

(Bavarian State Library CLM 849, translation from Kieckhefer (1998) 82)

The use of white doves and their blood in rituals for love, favour, and related practices thus offers an example of a very widespread practice, one which is so specific that it demonstrates that all of these traditions are related to one another. The Coptic examples may not be the most explicit – Coptic recipes are generally quite abbreviated, compared to the Greek or Latin recipes – but they are the earliest; an example in British Library MS Or 6796 (1-3) can probably be dated to around 600 CE, and so they allow us to see clearly how old these practices are.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Delatte, Armand. 1927. Anecdota Atheniensia: T. I: Textes grecs inédits relatifs à l’histoire des religions. Bibliothèque de la faculté de philosophie et lettres de l’Université de Liège, fasc. 36. Liège: Vaillant-Carmann.

Editions of several Byzantine magical texts from the Mediaeval and Early Modern periods, though without translations.

Dosoo, Korshi. 2022. “Suffering Doe and Sleeping Serpent: Animals in Christian Magical Texts from Late Roman and Early Islamic Egypt”, in Magikon Zōon: Animal et magie dans l’Antiquité et au Moyen Âge | Animal and Magic from Antiquity to the Middle Ages, edited by Korshi Dosoo and Jean-Charles Coulon. Paris-Orléans: Institut de recherche et d’histoire des textes, 2022, 495-544. URL

Discussion of the role of animals in Christian magic from Egypt.

Dosoo, Korshi, and Thomas Galoppin. 2022. “The Animal in Graeco-Egyptian Magical Practice.” In Magikon Zōon: Animal et magie de l’Antiquité au Moyenne Âge: The Animal in Magic from Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Edited by Korshi Dosoo and Jean-Charles Coulon. Paris: IRHT, 203-256. URL

A discussion of the role of animals in Greek and Demotic-language magical papyri.

Gilhus, Ingvild Sælid. 2006. Animals, Gods and Humans. Changing Attitudes to Animals in Greek, Roman and Early Christian Ideas, London and New York, Routledge.

An excellent discussion of the changing place of animals in ancient Mediterranean thought, with a discussion of doves on p. 173.

Khater, Antoine. 1970. “L’emploi des Psaumes en thérapie avec formules magiques cryptographiques”, Bulletin de la Société d’archéologie copte 19, 123-176.

Edition of the earliest published Copto-Arabic ‘Psalm Guide’.

Kieckhefer, Richard. 1998. Forbidden Rites: A Necromancer’s Manual of the Fifteenth Century. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press.

Translation and discussion of a fifteenth-century Latin magical handbook from Germany.

Saar, Ortal-Paz. 2014. “A Genizah magical fragment and its European parallels.” Journal of Jewish Studies 65.2: 237-262.

A detailed discussion of the parallels between the Jewish and Latin manuscripts mentioned here.

Saar, Ortal-Paz. 2017. Jewish Love Magic: From Late Antiquity to the Middle Ages. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

A discussion of Jewish love magic, including mentions of texts which use the blood of a white dove.