The story of Jonah, in its general outlines, is probably one of the best known in the Bible. Jonah was an Israelite prophet commanded by God to go to the people of Nineveh in Assyria to warn them that their wickedness had doomed them to divine punishment. For reasons explained at the end of the story, Jonah decided to disobey, and fled to the city of Joppa (modern Tel Aviv-Yafo). Here he boarded a ship bound for Tarshish, identified by modern scholars as southern Spain. As Herman Melville has a preacher tell it in Moby Dick (1851):

With this sin of disobedience in him, Jonah… flouts at God, by seeking to flee from Him. He thinks that a ship made by men will carry him into countries where God does not reign, but only the Captains of this earth. He skulks about the wharves of Joppa, and seeks a ship that’s bound for Tarshish […] in Spain; as far by water, from Joppa, as Jonah could possibly have sailed in those ancient days, when the Atlantic was an almost unknown sea… See ye not then, shipmates, that Jonah sought to flee world-wide from God?

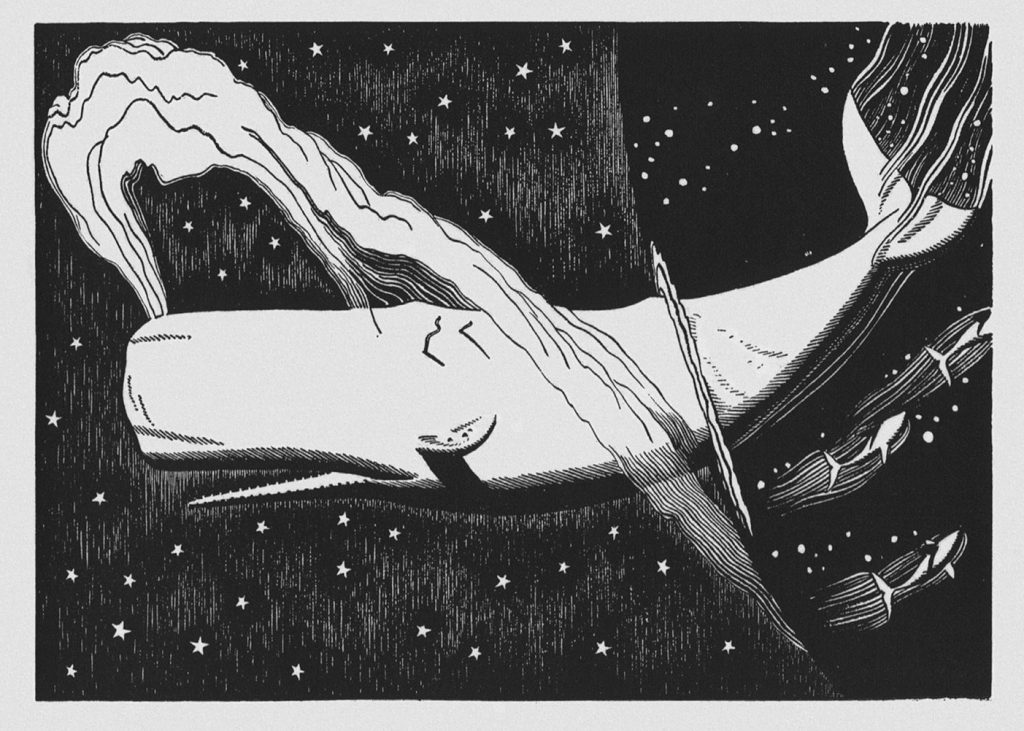

Of course, Jonah cannot escape, and God sends a storm which lashes the ship until it is in danger of being destroyed. The sailors perform a divination procedure using lots to determine who is responsible, which points the finger at Jonah. The prophet confesses, and tells them to cast him overboard to stop the storm. They do so, and he is swallowed by what the Hebrew Bible calls a “great fish” (dag gadol), and the Greek Septuagint calls a “giant sea monster”(kētos megalos), the same term used in the Coptic bible translations. Nowadays we tend to imagine this creature to have been a whale, the meaning of kētos in modern Greek, but ancient readers probably did not distinguish between fish and marine mammals. In Ancient Greek and Coptic, kētos could mean a tuna, a whale, a seal, or even the fantastic sea monster killed by Perseus. The standard iconography for such a creature, which shows up in Coptic depictions of the Jonah story, is of a creature with a dog-like upper body and a fish tail. Again, Melville sums it up nicely:

Be it known that, waiving all argument, I take the good old fashioned ground that the whale is a fish, and call upon holy Jonah to back me.

Jonah remains in the fish’s belly for three days and nights, before being regurgitated onto land, where he finally obeys the command of God and tells the people of Nineveh that God will punish them. The city is moved to repentance, and the humans and animals fast until God decides to relent. Jonah is unhappy with this outcome, and tells God that this is why he ran – he knew that if he warned Nineveh they would have repented and escaped judgement, but God reminds his prophet that it is his prerogative to have mercy on the humans and animals of the city.

© Musée du Louvre/ C. Larrieu

While it is one of the shortest books of the Bible, the story is particularly gripping, with its monstrous fish, Jonah’s miraculous survival, and a clear demonstration of divine mercy. Jonah was understood by later Christians as a prefiguration of Jesus – just as Jonah spent three days in the belly of the fish, Jesus spent three days dead and in the underworld.

The repentance of the people of Nineveh, which inspired the forgiveness of God, is the origin of the Coptic Fast of Jonah, or Fast of the Ninevites, introduced by Patriarch Abraham (reigned 975-979 CE), following an older Syrian custom. This three-day fast (taking its duration from Jonah’s stay inside the fish) is a time for repentance, during which members of the Coptic Orthodox Church are to abstain from any animal products, and the Book of Jonah is read aloud in church. The fast begins on a Monday two weeks before Lent, and is followed by the Feast of Jonah, which this year (2019) falls on the 21st of February.

The salvation of Jonah shows up in many other contexts in earlier Christian Egypt, among them the curse text known as Bodleian MS. Copt. c (P) 4 , dating to between the fourth and fifth centuries CE. It was folded once each way before being sealed, but when opened it contains the prayer of a man named Jacob, which begins as follows:

I am Jacob, the miserable, the wretched. I entreat, I invoke, I worship, I lay my prayer and my request before the throne of God the Almighty, Sabaoth. Perform my judgment (hap) and my vengeance (kba) against Maria, daughter of Tsibel, and Tatore, daughter of Tashai, and Andreas, son of Marthe, quickly!

Bodleian MS. Copt. c (P) 4 recto ll.1-3

This opening passage is interesting because, unlike a stereotypical “binding curse” of the type found in many older Greek texts, this invocation names the person who performs it, and represents itself as an appeal for justice rather than as simply an attempt to destroy an enemy. In many ways, it resembles the petitions which individuals in Late Antique Egypt might write to those in power – governors, bishops and so on – describing their miserable situation and asking for intervention. Here, though, Jacob is not petitioning a human magistrate, but God Almighty himself.

These features suggest that this text might belong to the class which Hendrik Versnel called “prayers for justice”, known from throughout the Roman world, which led him to question the division between magic and religion. But while Versnel noted that such prayers often listed the specific crimes committed against the petitioner, Jacob’s prayer is silent about what exactly Maria, Tatore and Andreas have done. It would also be somewhat unusual in naming them, rather than allowing God to decide who the guilty party was. Versnel also suggested that many of these prayers for justice might have been nailed up in a shrine, temple or church, allowing the guilty person to see or hear about it, and so make restitution – a neat, rational explanation for how magic might function. But the Coptic examples often seem to have been buried with corpses, a practice more similar to the earlier Greek binding curses, and to the even older Egyptian practices of letters to the dead and letters to the gods, deposited with human and animal mummies respectively.

© Musée du Louvre / Georges Poncet

Before we move on to find Jonah, we should note another interesting feature of this text: it is written by a man against three victims, of whom two, Maria and Tatore, are women. This is quite unusual, but suggests that we are dealing with a context in which women played an important social role outside of the home. None of the women are obviously related to Jacob or to each other, so whatever they did to elicit his anger, there is nothing to suggest it was a familial squabble.

While the full text is very long, invoking a long series of Christian divine beings over thirty-nine lines, Jonah shows up in line 21:

Oh you who rescued Jonah from the sea monster (kētos), strike Tatore and Andreas and Maria!

Bodleian MS. Copt. c (P) 4 recto ll.21-24

Oh you who saved the three saints from the burning fiery furnace, strike Tatore daughter of Tashai, and Maria daughter of Tsibel, and Andreas son of Marthe, with great anger and great destruction and ruin!

Oh you who rescued Daniel from the lions’ den, strike Maria and Tatore and Andreas with the anger of your wrath! (recto 21-24)

Here Jonah joins Daniel and the Three Hebrew Youths as a paradigm of an individual saved by God’s mercy, and Jacob hopes to be saved in just the same way.

This may seem like an unusual curse text, and in many ways it is, but it is useful in giving us a glimpse into the mentality of someone who might have commissioned such a ritual. We often imagine curses as cruel and malicious, but, as Christopher Faraone has observed, curse texts often take a “defensive stance”, implying that, like Jacob, their users imagined themselves as attacking others in order to protect themselves. We don’t know exactly what Maria, Tatore and Andreas did to him, but in this text Jacob describes himself as trapped, like Jonah was trapped in the belly of the fish, and in need of God’s direct intervention.

References and Further Reading

Atiya, Aziz (editor). “Biblical Subjects in Coptic Art, Jonah“, “Lectionary“, “Fasting“. In The Coptic Encyclopedia. New York: Macmillan, 1991.

Bosson, Nathalie . “6–9.2.2.2 Minor Prophets”. In Textual History of the Bible. Edited by Armin Lange. Brill, 2016. URL

Crum, Walter E. “Eine Verfluchung.” Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde 34 (1896): 85–89.

The original edition of MS. Copt. c (P) 4, the Coptic curse text discussed above.

Faraone, Christopher A. “The Agonistic Context of Early Greek Binding Spells”. In Magika Hiera. Ancient Greek Magic & Religion. Edited by Christopher A. Faraone and Dirk Obbink. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991, 3-32. URL

An excellent discussion of the social context of Greek binding curses, which mentions the “defensive stance” taken by many of them.

Meyer, Marvin W., and Richard Smith. Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts of Ritual Power. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press, 1999, pp. 192-194, no. 91.

English translation of MS. Copt. c (P) 4, the Coptic curse text discussed above.

Versnel, Hendrik S. “Some Reflections on the Relationship Magic-Religion.” Numen 38.2 (1991): 177–197. URL

Versnel, Hendrik S. “Beyond Cursing: The Appeal to Justice in Judicial Prayers”. In Magika Hiera. Ancient Greek Magic & Religion. Edited by Christopher A. Faraone and Dirk Obbink. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991, 59-106. URL

Versnel’s most developed discussion of the concept of “prayers for justice”.