© Musée du Louvre/C. Larrieu [source]

There is a famous story told by the English printer William Caxton in the introduction to his 1490 edition of the Aeneid, about a group of merchants headed from London to Denmark who stopped along the way at a woman’s house to see if they could get something to eat. One of them, from the North of England, asked if she had any eggs, and she replied that she didn’t speak French, something that must have confused them both, until one of his companions stepped in and told the woman that he wanted eyren. The woman was as English as the merchant, but the problem was caused by a difference of dialect – the man, from the north of England once ruled by the descendants of the vikings, used the Scandinavian word “egg” for the original English word “ey” (made plural, like “child”, by adding –ren to the end). The fact that we all now talk about “eggs” and not “eyren” is not because the first word is older, better, or more correct, but because of the largely random ways in which languages evolve, with different variants appearing and disappearing over time.

Coptic, like English, and all other languages, was a language which contained a great deal of variation, which is usually thought of in terms of “dialects”. This is actually the point of Caxton’s story – as a printer, he had to decide which version of English to use, knowing that whatever choice he made would seem incorrect to many readers. The development of the printing press, along with dictionaries, and the development of modern nation states, has considerably standardised English since Caxton’s time, and other languages with official or semi-official status have gone through similar processes, but much variation still remains.

We can think about variation within languages in several ways. One of the most obvious is in spelling – when we learn to write, we learn the accepted spellings of words, but there are some variations – most notably, between the British and American standards – which might give future historians a hint of the origin of writers. So, for example, the spellings “labour” and “labor” don’t tell us anything about how a writer pronounced a word, but they do tell us something about the style of English – British or American – in which they were trying to write.

Another obvious difference is in the pronunciation of words. People in Caxton’s time often wrote in a way that reflected the way they spoke; for example, he writes “a house” as an hows, showing us that he didn’t pronounce the “h” in house. The standardisation of spelling means that these kinds of variations are less visible in modern written English, but occasionally unusual spellings or mistakes can reveal the kind of English someone speaks – a 2019 article from the Independent miswrote “uncharted territory” as “unchartered territory”. This suggests that the writer has a non-rhotic accent in which the /r/ sound isn’t pronounced in some positions, typical of England and Australia, rather than a rhotic accent, typical of America, Ireland or Scotland; in accents of this kind “-ed” and “-ered” may sound almost the same. Another obvious variation is in word choice – is coca cola a type of “soda”, “pop”, “coke”, or “fizzy drink”? The terms we use for such mundane things can often reveal a lot about the type of English we speak. Finally, we can also look at grammar; in Standard English double negation is usually seen as incorrect, or expressing a positive meaning (“I didn’t do nothing” = “I did something”), but this is not the case in many, and perhaps most, languages, and in many varieties of English double negation is considered normal. It just happens that, in the course of history, a type of English that doesn’t use double negation has come to be considered standard.

Perhaps because Coptic was not subject to a centralising, standardising force for most of its history, its written forms reflect considerable dialectal variation. Coptic is usually considered to have six major dialects – Bohairic, Fayumic, Mesokemic (or Middle Egyptian), Sahidic, Lycopolitan (or Sub-Achmimic), and Achmimic – which are often further divided into many subdialects. Like Britain or Italy, the Nile Valley is a narrow strip of inhabitable land stretching from north to south, and so the dialects form a continuum – the dialects of regions close to one another are similar, with those from the extreme north and south being very different. In fact, we can find an awareness of this difference reflected in certain literary texts; in a story called the Life of Aaron a group of men from Philae, in the far south of Egypt, are visiting Alexandria, in the far north, and as they look for a way to get home, a captain of a boat from Elephantine, near their home city, hears them talking, and says to them:

“Where are you from? Because I see that your language is like ours.”

Life of Aaron 30b-31a (7th-10th century CE)

This scene – a traveller far from home hearing a familiar accent – is a common one throughout history. But although these dialectal differences are most visible in Coptic, it is likely that they were present throughout the history of the Egyptian language, even if the strong centralising state was able to suppress most variation in the written forms of the language. We can find a hint that the spoken language was more diverse in a letter from the New Kingdom, in which a sarcastic writer complains that

There is no translator who can translate (your letter); it is like a conversation between a man of the Delta and a man of Elephantine

pAnastasi I 28.6 (late XIX dyn., 1292-1189 BCE)

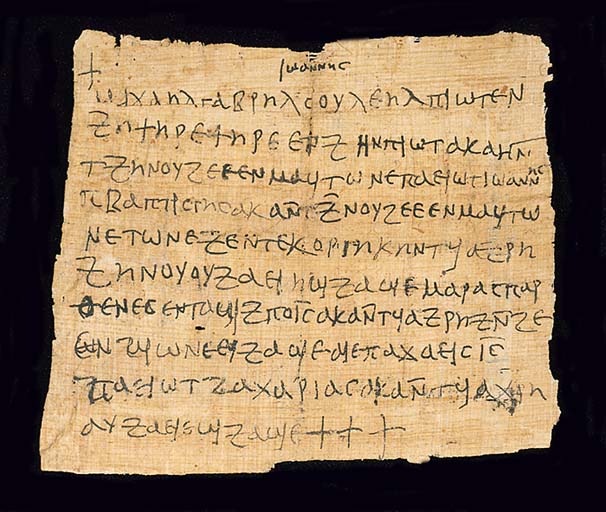

Just as in English, Coptic dialects may vary in their spelling conventions, in their pronunciation, their vocabulary, and their grammar, and we find this variation reflected in the magical papyri. Our database currently contains 524 Coptic magical manuscripts, of which 335 have dialectal information noted. In some cases, we may not have dialectal information because the texts are too short to allow us to analyse dialect, in others we may simply not yet have had time to perform an analysis, and many of the judgements of previous editors will need to be revised. Nonetheless, the statistics are still useful to get a sense of the dialectal variation in the corpus.

| Dialect | Number of Coptic Magical Manuscripts |

| Bohairic | 9 |

| Fayumic | 41 |

| Mesokemic | 4 |

| Sahidic | 267 |

| Lycopolitan | 2 |

| Achmimic | 12 |

We can see that we have some texts in all of the major dialects of Coptic, but that the division between them is very uneven. Most are in Sahidic, a dialect which perhaps originated around the region of Hermopolis, but which seems to have become the written standard quite early, used throughout the country. We can see a parallel here to the way in which the English of south-east England or the French of Paris, originally just local dialects, became considered the standard and “correct” forms of their language over time. Sahidic was the predominant dialect for all Coptic texts until the 9th century, and so its dominance in magical texts, as in letters, legal texts, and other genres, is not surprising. What is interesting, though, is that a large number of the ‘Sahidic’ texts are non-standard; that is, they demonstrate abnormal features which suggest that the person writing them had not mastered the written standard, so that features of their spoken dialect slipped in. One of the most common of these is the addition of a short vowel between consonants in many words; in standard Sahidic the word for “hear”, for example, is sotm (ⲥⲱⲧⲙ), but often we find instead something like sotem (ⲥⲱⲧⲉⲙ). We could compare this to the way that some English speakers add vowels to certain words, sometimes writing “athlete” as “athalete” or “nuclear” or “nucular”.

The next highest proportion of manuscripts are in the Fayumic dialect, associated with the oasis west of the Nile valley; as discussed in a previous post this is one of our major sources of ancient manuscripts. Cut off from the rest of the Nile Valley, Fayumic developed several distinctive features, the most notable of which was often pronouncing /r/ as /l/ – “man”, rome in Sahidic, is lomi in Fayumic.

The other dialects are far less represented; in some cases, as in Mesokemic, this may be because the dialect is far less distinctive than Fayumic, so that it may be that previous editors have misidentified a Mesokemic text as non-standard Sahidic. Something similar may be the case with Achmimic and Lycopolitan, the two southern dialects, which are quite close to one another and often difficult for those not familiar with Coptic dialects to distinguish. Most of the texts in these last two dialects are quite early – dating to before 600 CE – so that it may be that Sahidic almost completely replaced them as a written dialect in southern Egypt after this point.

The last dialect, Bohairic, is not very well attested in our database, but is important for the study of Coptic. Used in the north of Egypt, it became the standard dialect around the ninth century, after the Patriarch of Alexandria, the Coptic Pope, established a secondary residence in the Monastery of Apa Macarius in the Wadi Natrun, west of the Delta, where Bohairic was the standard written dialect. In a modern Coptic Church, the form of Coptic used in the liturgy is normally Bohairic, modified in the 19th century to have a pronunciation closer to modern Greek. Most of the Bohairic texts are late, dating to the 8th century or later, but it’s interesting that even in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, when Bohairic had largely displaced Sahidic as the standard language, Sahidic is still used more than Bohairic in magical texts. It may be that Sahidic continued to be thought of as an archaic or classical form of the language, even as most Egyptians began to speak Arabic, and as the Church replaced Sahidic with Bohairic in its liturgy.

This post has been quite technical – the details of dialectal variation are often not learnt by students of Coptic until their second year, if at all – but the fact that Coptic retained a diversity often lost in written languages is something quite exciting, which helps us to get a sense of the geographical origins and education of those who wrote the language in all of its varieties.

References and Further Reading

Funk, Wolf-Peter. “Dialects wanting homes: a numerical approach to the early varieties of Coptic” in Historical Dialectology: Regional and Social, edited by Jacek Fisiak (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1988), 149-92.

Budge, E. A. Wallis. Miscellaneous Texts in the Dialect of Upper Egypt. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1915, 948-1011.

Contains an edition of the Life of Aaron; a new and improved edition by Jitse Dijkstra and Jacques van der Vliet should appear in December 2019.

Wente, Edward. Letters from Ancient Egypt (SBL Writings from the Ancient World Series 1) (Atlanta: Scholard Press, 1990), 98-110.

A recent English translation of pAnastasi I.

2 Comments

Gary S. Dykes

Why did you not mention Hans Deter Betz? Or are you not aware of his work on Coptic magical papyri? Anyways, I liked you article!

Gary

Korshi

Hi Gary, thanks for commenting! Hans Dieter Betz worked extensively on the Greek magical papyri, and there are a few Old Coptic texts in the translations of the PGM which he edited (although the translations are by Marvin Meyer), but he didn’t really work on the Coptic magical corpus, and I don’t think he worked at all on Coptic dialects, which is why we don’t mention him in this post.