As we saw in our Christmas post, the Coptic Church celebrates the major Christian festivals at a different date to the Western churches because it uses the older Julian calendar rather than the now dominant Gregorian calendar. For this reason, Coptic Christians, along with the members of several other Eastern and Oriental Orthodox churches, will celebrate Easter (Coptic ⲡⲁⲥⲭⲁ, paskha) on the 28th April 2019. While modern Christians, especially those in cold climates, often think of Christmas as their major celebration, Easter is the first festival attested in the ancient church, and remains for many the most important. We find the basic outlines of its story in each of the Gospels, as well as in the letters of the Apostle Paul – Jesus was crucified and died on Good Friday, and on Easter Sunday he miraculously arose from the dead. His followers came to interpret this as simultaneously a sacrifice – Jesus giving himself up for the sins of humanity – and a victory – Jesus conquering death and the Devil, and thus serving as a promise of future eternal life to his followers.

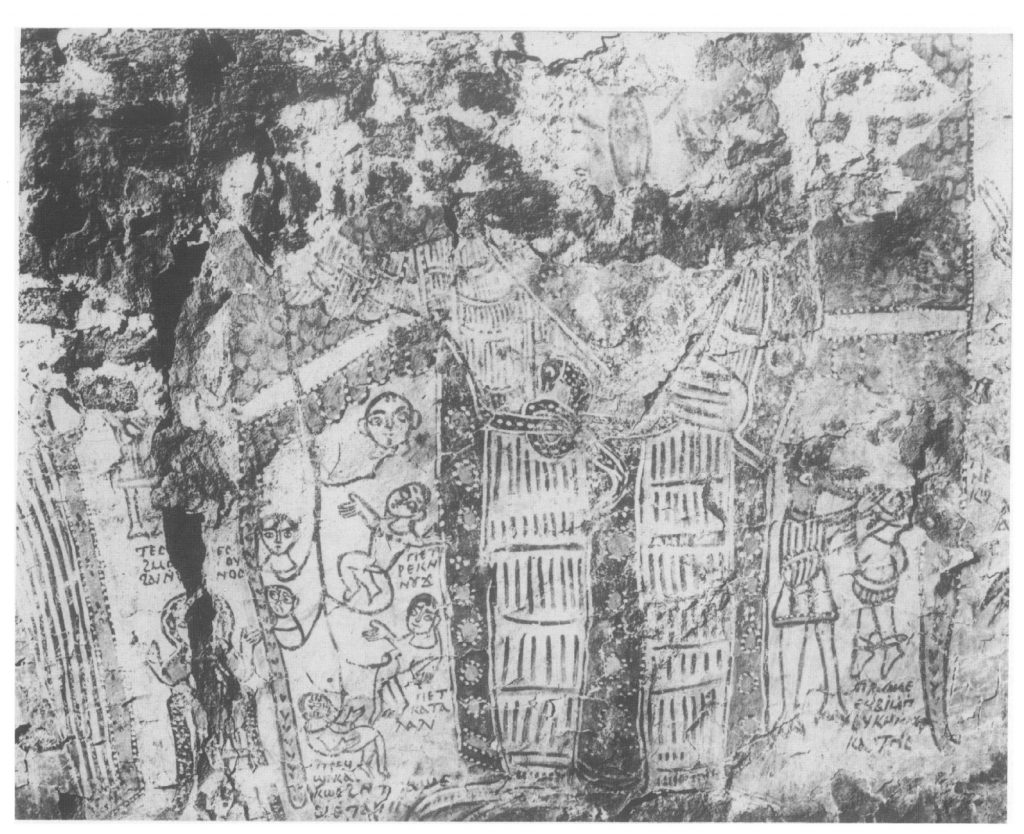

British Museum 1878,1203.4 (ca. 1300 CE) a cedarwood panel from the Sitt Miriam church in Egypt depicting the Harrowing of Hell. In the centre Jesus pulls Adam and Eve from an open tomb representing hell, while the various prophets whom he has already rescued stand behind him. At the bottom, two angels bind the Devil in chains.

One part of this story which is less known today, but which played a large role in the early Christian imagination, was the Harrowing of Hell. During the period that Jesus was dead – Holy Saturday – he was believed to have descended into hell (Coptic amente, Greek hadēs), where all the human dead were imprisoned, and rescued the souls of the righteous men and women of the past – the Hebrew Patriarchs and those who dwelled with them. This is described in dramatic terms – early Christian texts have Jesus breaking the bronze doors of hell and shattering their iron bolts, and the Coptic Book of Bartholomew (written sometime between the 5th and 10th centuries CE) describes Jesus storming hell in a shining chariot, leaving it in ruins and binding the Devil in chains. The events of Good Friday, Holy Saturday and Easter were not simply theological concepts to the Christians who wrote these texts, but powerful promises that they and those they loved could be saved from evil and from death itself.

As we have seen, Coptic magical texts often draw upon key moments of Christian myth, and so it is not surprising that we find one which draws upon the Easter story; what is perhaps surprising is the appearance of a unicorn.

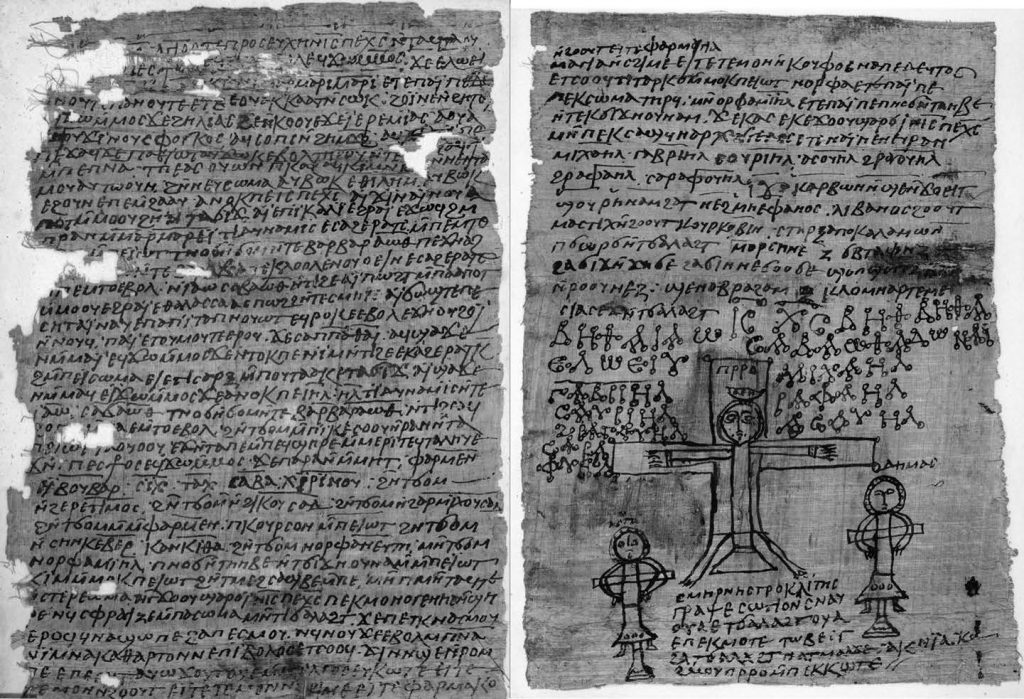

British Library MS Or 6796 (4) + MS Or 6796 is a set of two sheets written on papyrus around 600 CE, and probably found in the region of Thebes in southern Egypt, where it was purchased for the British Museum in 1907, before being given to the British Library when it was separated from the Museum. Along with three other manuscripts, it belongs to an archive which was copied for or by a man named Severos, son of Ioanna. The manuscript contains a prayer for protection from evil, asking for Jesus and the archangels to be sent to the person using the ritual to protect them from demons and hostile magic by creating an enormous barrier 120 miles in radius.

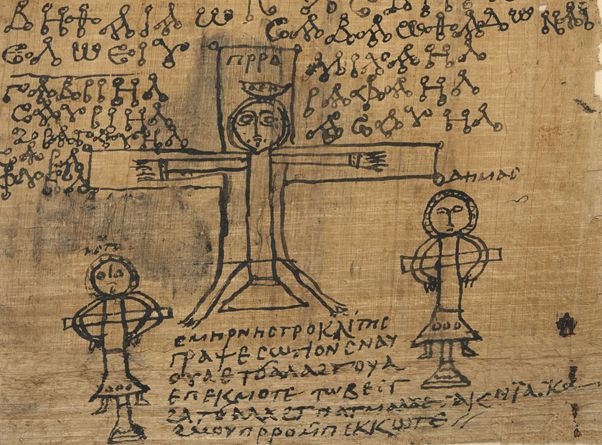

The manuscript ends with a drawing unique in the surviving magical corpus, of Jesus being crucified with the two thieves. Jesus himself wears a crown with the first three of the Greek vowels written upon it, symbols of the primal elements of the universe, and the word “king” (Coptic ⲡⲣⲣⲟ, p-rro) written above his head. Around him are written various sacred names, including those of God the Father and the seven archangels, written in the style of the magical symbols we call kharaktēres, with decorative circles at their points. The two thieves on either side of him are shown being crucified with their arms tied behind the horizontal branches of their crosses – this is a common feature of early depictions of the crucifixion, in which Jesus has his arms straight, while the thieves are crucified in what scholars of iconography call the ‘oriental’ form. Like Jesus, the two thieves have their names written above them – Gestas and Demas – slight variations of names which appear in apocrypha such as the Gospel of Nicodemus. While this may not be the most expert depiction – the artist seems to have become confused about where the body of Jesus ended and the cross began – it is well grounded in the Christian tradition, both in terms of its iconography and its use of the popular names of the characters.

The text itself begins with a description of the moment of crucifixion, with jesus crying out the famous words, Eloi, Eloi, Lama Sabakhthani, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” in Aramaic; these are Jesus’ last words according to the Gospels of Mark and Matthew. He is given vinegar to drink, and says “My Father, all things have been completed”, events taken from the Gospel of John. He dies, the earth quakes, heaven opens, and the bodies of the dead rise and go to Jerusalem – events taken from Matthew again. Like most tellings of the crucifixion, then, this version draws upon several of the gospels at once to create a dramatic account of the story which is shown in the image below it.

The crucial part of the text is still to come, however. Next, Jesus speaks in the first person, describing how he took a cup of water and spoke a prayer over it in the name of the powers of God the Father, whom he calls by his Hebrew name Iaō Sabaōth. He pours the cup of water into the sea, which parts to reveal a golden field at the bottom, in which lies a unicorn. The unicorn is surprised to see him, and demands:

“Who are you who stands here thus, in the body, yea, in the flesh, who has not been given into my hand?”

London Oriental Manuscript 6796 [4], 6796 ll.19-20

Jesus replies by giving his secret name, revealing his divine identity:

“I am Israēl Ēl, the force of Iaō Sabaōth, the great power of Barbaraōth.”

London Oriental Manuscript 6796 [4], 6796 ll.21-22

The unicorn is terrified by this, and flees from him.

Understanding this strange story reveals several interesting details of popular belief in Late Antique Egypt, and is necessary to explain the mechanism behind the magical text of which it is part. To begin, let’s look at a parallel, a story from the fragmentary Coptic Acts of Andrew and Paul. In this story Apostle Paul is sailing when he decides that he wants to see the Abyss, “where the Lord had gone, [so that he can] see what He did”. He gives his cloak to a sailor, telling him to bring his fellow apostle Andrew to rescue him, and leaps into the sea. A few days later, the sailor brings Andrew to find Paul. They take the ship to the point where Paul jumped into the water, and Andrew fills a cup with fresh water before praying to Jesus and pouring it into the sea, which parts to reveal Paul, who leaps out, holding a piece of wood. He recounts how he has been in hell, where he saw the empty places where the souls of Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and the Hebrew prophets had been before they were saved by Jesus. This is what he meant when he said he wanted to see “where the Lord had gone [and] what He did” – he wanted to visit hell and see where Jesus had been on Holy Saturday. Although the part he was in was empty, he could still hear the distant wailing from the places where other souls remained – those of murderers, magicians (pharmakoi) and infanticides. Before Andrew came to rescue him, he managed to grab a hinge from one of hell’s shattered gates – the piece of wood he carried.

This parallel reveals the identity of the golden field: it is hell, and although Jesus descends there by parting the waters of the sea, the story in the magical text is probably meant to recount his descent there on Holy Saturday after his crucifixion. To understand the identity of the unicorn, though, we have to look at another parallel. We have already briefly mentioned the Book of Bartholomew, a Coptic account of the Harrowing of Hell. According to this story, Abaddon, the Angel of Death, is confused when Jesus’ soul does not appear in hell after his death. He goes to Jesus’ tomb with his six children, who take the form of writhing serpents or maggots, and finds Jesus’ body there. Abaddon is horrified to find that Jesus is able to talk to, and even laugh at him, Death, the terrifying angel who every living creature fears. He demands to know:

“Tell me then, who are you, oh you who mock me…. I have no power over you!”

Book of Bartholemew (Westerhoff 1999, 64)

Just as in the magical text, the dead Jesus is confronted by a figure who is surprised to find he has no power over him, and demands to know who he is. From this clear parallel we can see that the unicorn is intended to be Death, or a figure performing the same role, the ruler of the hell to which Jesus has descended. But why is he a unicorn, and not a monstrous angel? In the Christian tradition, the unicorn is usually understood as a symbol of Jesus himself, a miraculous animal whose single horn represents the oneness of God, and who can only be tamed by a virgin, just as Jesus was born through the Virgin Mary.

The solution can be found in the words spoken by Jesus on the cross – “My god, my god, why have you forsaken me?” As the earliest readers of the gospels would have known, these are the opening words of Psalm 21 (22 in Western Bibles), a prayer for help spoken by someone in dire straits. It continues:

Rescue my soul from the sword, and from a dog’s claw my only life!

Psalm 21.21-22 (NETS translation of the Septuagint)

Save my from a lion’s mouth, and my lowliness from the horns of unicorns!

The word “unicorn” (Greek monokerōs, Coptic papitap nouōt) is used here in the Greek and Coptic translations of the psalm, but the original Hebrew word was re’em, which is often understood as referring to the huge, though now extinct, bulls called aurochs. As we have noted, most early Christians used the Greek translation of the Hebrew scriptures produced in Alexandria in the third century BCE and known as the Septuagint. The Alexandrian translators, perhaps unfamiliar with aurochs, seem to have had another giant horned creature in mind when they translated re’em as unicorn – the rhinoceros, which they may even have seen during a festival held by one of the Ptolemaic kings. Early Greek and Latin writers tended not to make the same distinction between the fabulous unicorn and the real rhinoceros that we do today. The association of the unicorn with evil in this passage led to a secondary association, the unicorn as a symbol of the Devil, an equation which is explicit in a sermon by the fifth-century Coptic author Shenoute. Other early Christian authors saw the unicorn’s horn as a symbol of the cross, upon which Jesus had been crucified, and thus a symbol of his death.

This tour of texts from ancient Christianity has finally allowed us to understand the magical text in its entirety. It begins with a description of Jesus’ death upon the cross, before he descends to hell, which here lies beneath the waters of the sea rather than under the earth. There he confronts the demonic ruler of hell, the unicorn. He reveals his secret name, causing this symbol of ultimate evil to flee. The spell ends with a prayer to God the Father to send Jesus to protect the user, to cause evil forces to flee from them just as the unicorn fled before Jesus before. The magical text’s power comes in part from the secret knowledge it contains – the hidden names of Jesus and God the Father, spoken in the story and written in the image – but also from the larger power of the Easter story, the Christian belief in the victory of Jesus over death and the Devil.

I would like to offer my sincere thanks to Christian Bull for providing me with his English translation of the Acts of Andrew and Paul.

Bibliography and Further Reading

The Claremont Coptic Encyclopedia

Useful general information on the celebration of Easter in the Coptic tradition may be found in the articles Feasts, Major and Pascha.

Alcock, Anthony. Acts of Andrew and Paul. URL

A translation in English of the surviving fragments of the Acts of Andrew and Paul.

Balicka-Witakowska, E. “The Crucified Thieves in Ethiopian Art: Literary and Iconographic Sources”. Oriens Christianus 82 (1998), 209-211.

A discussion of the iconography of the crucifixion of the two thieves.

Budge, Ea. Wallis. Coptic Apocrypha in the Dialect of Upper Egypt. London: 1913, 179-230. URL

Contains an English translation of the Book of Bartholomow.

Downer, Carol. “A Ban on Unicorns? Decorative Motif and Illumination in M581”. In Coptic Studies on the Threshold of a New Millennium: Proceedings of the Seventh International Congress of Coptic Studies. Leiden, 27 August – September 2000, edited by Mat Immerzeel and Jacques van der Vliet.

Leuven; Peeters, 2004, vol.1, 1205-1219.

A useful study of the unicorn in the context of Late Antique Egyptian Christianity.

Einhorn, Jürgen W. Spiritalis Unicornis: Das Einhorn als Beteutungsträger in Literatur und Kunst des Mittelalters. Munich: Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1998.

A study of the unicorn and its interpretation over time. A discussion of the Devil as a unicorn can be found on pages 134-138.

Godbey, Allen H. “The Unicorn in the Old Testament”. The American Journal of Semitic Languages and Literatures 56.3 (1939), 256-296.

Kropp, Angelicus. Ausgewählte koptische Zaubertexte. Textpulikation. Vol. 1, Bruxelles: Édition de la Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, 1931, no. J, pp. 47-49.

The original edition of British Library MS Or 6796 (4) + MS Or 6796, the magical text discussed here.

Martín-Hernández, Raquel. “El poder de las imágenes en la magia a partir del s. IV d. C. Las representaciones de Jesús.” In Los orígenes del cristianismo en la literatura, el arte y la iconografía II, edited by J. A. Álvarez Pedrosa, M. López Salva and I. Sanz Extremeño. Madrid: 2018, 255-268. URL

A discussion of representations of Jesus in magical texts, including

British Library MS Or 6796 (4) + MS Or 6796.

Meyer, Marvin W., and Richard Smith. Ancient Christian Magic: Coptic Texts of Ritual Power. Princeton (New Jersey): Princeton University Press, 1999, pp. 290-292, no. 132.

A translation of British Library MS Or 6796 (4) + MS Or 6796 can be found here as text no. 132.

Sanzo, Joseph E. “The Innovative Use of Biblical Traditions for Ritual Power: The Crucifixion of Jesus on a Coptic Exorcistic Spell (Brit. Lib. Or. 6796[4], 6796) as a Test Case.” Archiv für Religionsgeschichte 16 (2014): 67–98. URL

A useful discussion of British Library MS Or 6796 (4) + MS Or 6796 and its interpretation.

Suciu, Alin. “The Book of Bartholomew: A Coptic Apostolic Memoir”. Apocrypha 26 (2015): 211-237.

A study of the Book of Bartholomew and its historical context.

Westerhoff, Matthias. Auferstehung und Jenseits im koptischen “Buch der Auferstehung Jesu Christi, unseres Herrn”. Wiesbaden: Harrossowitz Verlag, 1999.

Text and German translation of the Book of Bartholomew.