Image © 2019 The University of Chicago

In the last blog post in this series, we looked at the different materials upon which magical texts might be written – from papyrus sheets to lead tablets, and from parchment to animal bones. In this post we’ll look at the different ways that these raw materials could be turned into manuscripts which could be written upon, while in the next we’ll look at the ways in which the use of these formats changed over time. These two posts will discuss some of the material presented by Korshi Dosoo and Sofía Torallas Tovar at the 29th International Congress of Papyrology in July of this year, but it will leave aside Demotic and Greek material to focus on Coptic magical texts.

While ostraca, tablets and bones have a relatively fixed form due to their material, there are four major manuscript formats used in magical texts written upon papyrus, parchment, and paper: the roll, the codex, the rotulus, and the sheet. We might compare these to the different formats a book can take in the 21st century. When we think of a “book”, we typically imagine an object printed on paper, and bound with a spine which allows us to leaf through individual pages. But this format – the codex – was not the original form that books took, and may not be their main form for much longer. Alongside this printed codex, we also now have e-books – which can be read on computers, e-readers, and smartphones, either page by page or in a continuous scroll – and audiobooks, which recapture the experience of being read to, probably the way that most humans experienced books before the modern phenomenon of mass literacy. The same books can exist in all three formats (and more), but individual readers may prefer one format or another, and the use of these different formats continues to change over time due to shifting technology and social norms. The same was true of ancient books and their readers, and the history of Coptic magical manuscripts provides us with a miniature case study of these changes.

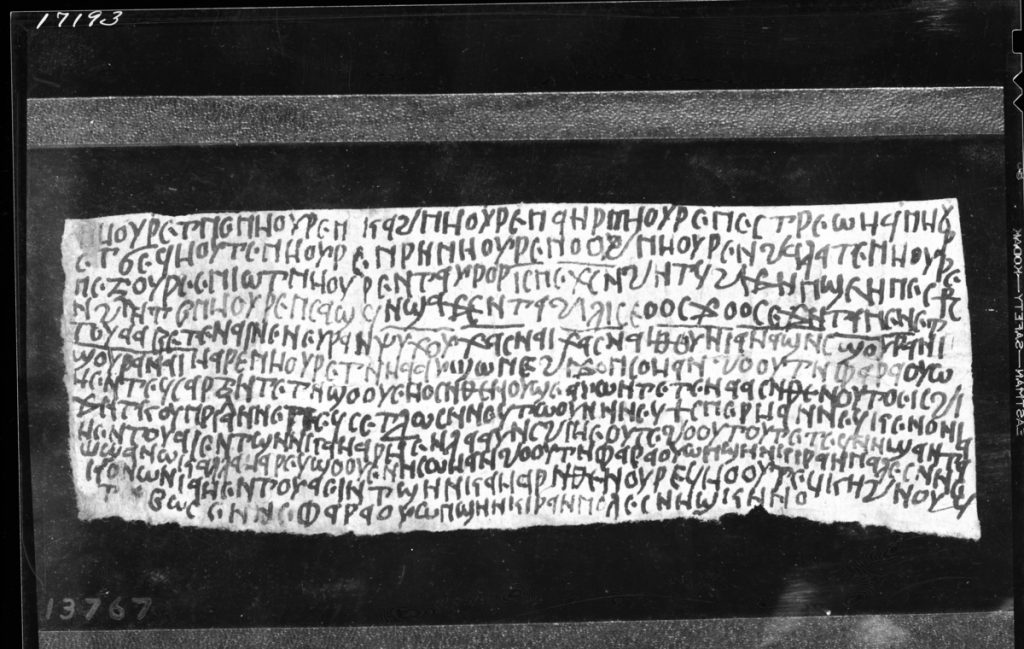

The original format for books in Egypt was the roll, a format later adopted by writers of other languages, such as Greek and Latin. The roll was a horizontal roll of papyrus, usually 20 to 30 centimetres high, and as long as it needed to be for the text it contained. The earliest examples are found at the very beginning of literacy in Egypt, and the roll remained the main format well into the Roman period, before it began to be replaced by newer formats such as the codex and rotulus. Rolls would be written in multiple columns: texts written in Egyptian scripts tend to have quite wide columns – often as wide as 20 centimetres – whereas Greek rolls tend to have much narrower columns – usually around 5 centimetres – allowing the eye to take in the entire line at once. The overall length of the rolls was also highly variable – Greek and Latin rolls tended to be a maximum of 10-20 metres in length, although Egyptian-language rolls could be significantly larger, with the largest surviving example, Papyrus Harris I (12th century BCE), being 41 metres long, and there are many other examples of similar size. Readers would not usually unroll an entire roll, however – rather, they would gradually scroll from column to column, rolling up the parts that they had already read, much in the same way as we scroll horizontally on a long webpage. While most 21st century literates, used to the codex, would find rolls awkward to use, they did have some advantages – they were simple to make, since papyrus was produced and sold in rolls, so that all one needed to do was to start writing. Likewise, while they were not normally fully unrolled, they could be, and even partially unrolled, it was possible to view multiple columns at once, something very difficult with a codex, where it is not usually possible to see more than two facing pages at the same time.

There are many magical texts written on rolls, but most of these are written in Demotic and/or Greek. Since the roll was largely replaced by the codex from the fourth century onwards, and most of our Coptic magical texts date from after this period, there are very few Coptic magical manuscripts upon rolls. Those which exist tend to be quite short compared to the earlier magical texts on rolls in Demotic and Greek, the longest of which can reach 3-5 metres in length.

Image © 2019 Smithsonian Institution

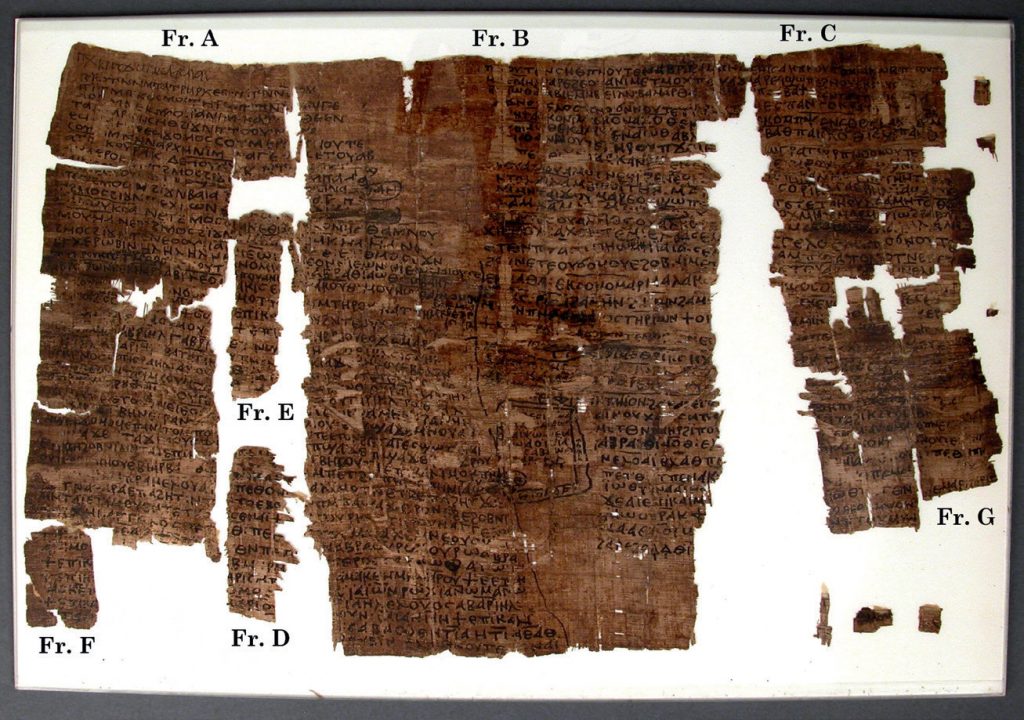

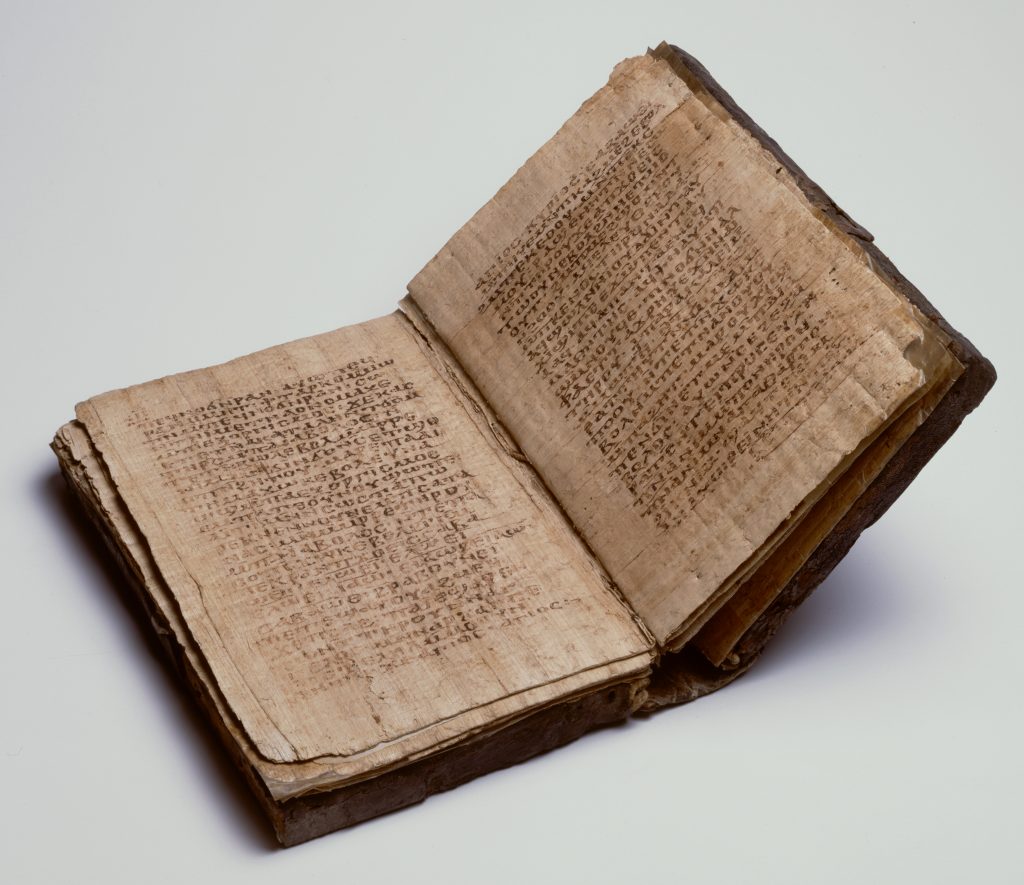

The codex (plural codices), the format which we are most used to, was first created by folding a small sheet of papyrus or parchment in two to create four separate pages, which could then be read one by one. This 4-page manuscript, known as a bifolium (Latin) or bifolio (Italian) is the building block of the codex, with larger codices formed by putting several bifolios on top of one another to produce books of much larger sizes. Since simply piling sheets on top of one another eventually becomes impractical for folding, longer codices were generally made by stitching together multiple bundles, which are individually known as gatherings or quires; often, quires were made of groups of four bifolios, a unit known as the quaternion. The huge Codex Sinaiticus (4th century CE), containing the entire New Testament, much of the Old Testament, and several apocryphal books, was produced with at least 96 quires. Codices often had covers, made from wood, leather, or papyrus, at times stiffened with cardboard made from more papyrus, which offered them additional built-in protection which rolls lacked, and which could be decorated.

There are some rather substantial magical codices – one of the largest is the famous Great Magical Papyrus of Paris (=PGM IV, 4th century CE), which is 72 pages long and contains some of the earliest Coptic magical texts, many of which we have discussed in past posts. Like most magical texts, though, it consists of a single quire, and although there are perhaps half a dozen which consist of two quires, we haven’t found any examples of predominantly magical codices consisting of three or more. One notable feature of the Great Magical Papyrus is that it is much narrower than the codices we are used to nowadays; this is true of many early papyrus codices, which seem to copy the narrow format of the columns of earlier Greek papyrus rolls.

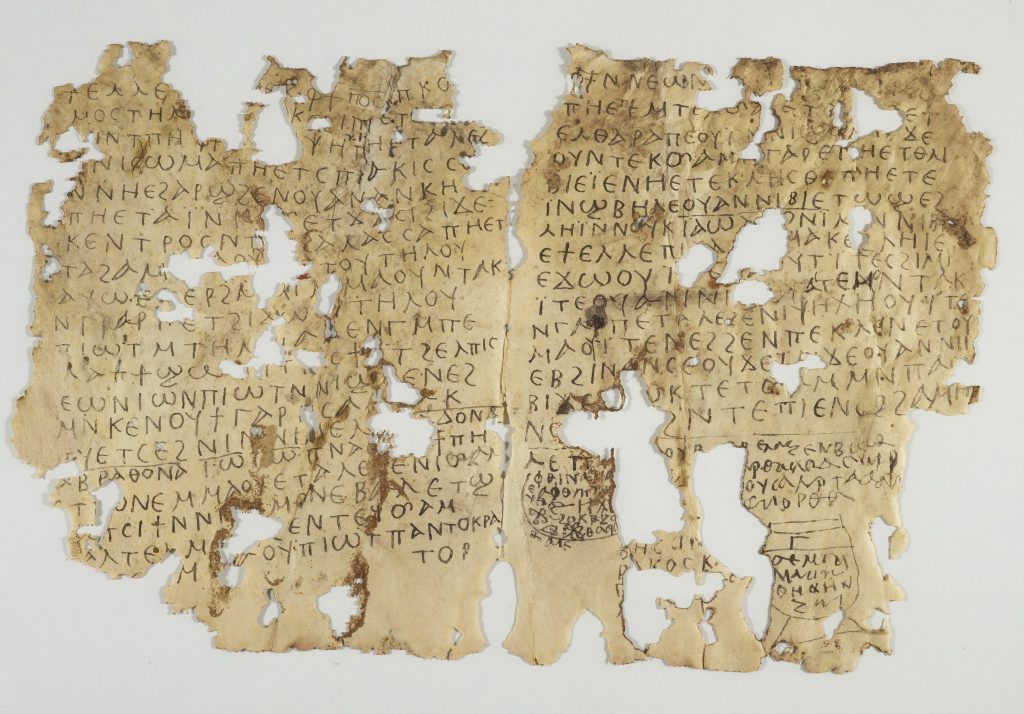

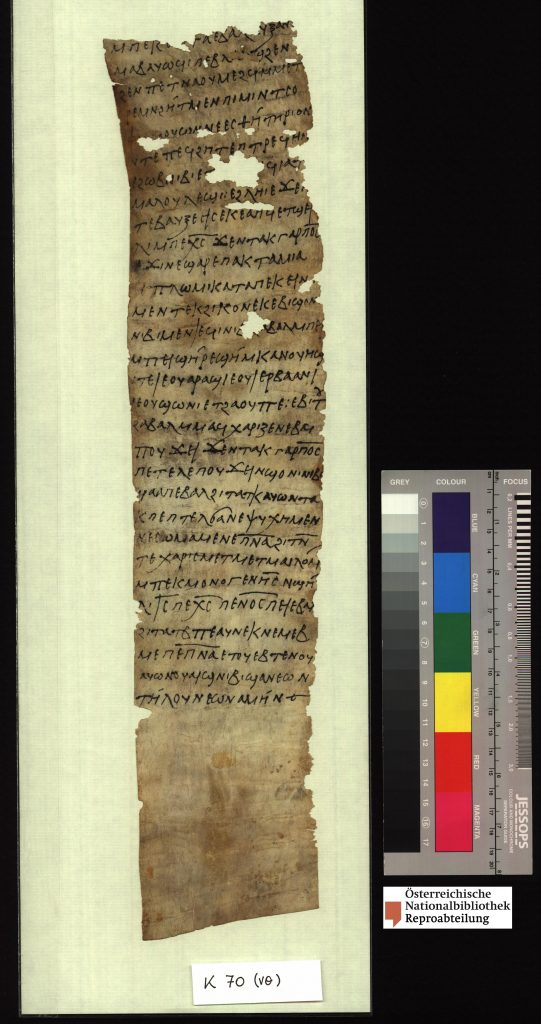

The third major format, the rotulus, consists of a roll turned 90 degrees, to form a vertical roll read from top to bottom instead of from left to right, so that the experience of reading one is very much like scrolling down a webpage. This format became particularly common from the sixth-century, for reasons we will discuss next week.

The fourth, and last format is the sheet, consisting of a single piece of papyrus, parchment or paper – usually less than 30 centimetres in any direction – written on one or both sides. Although often overlooked, the sheet is a very important format among Coptic magical texts, as we see when we look at the quantities of different formats in as represented by surviving manuscripts.

Looking at the 510 manuscripts in our database containing Coptic magical texts, we can see that the sheet is by far the most common format, used in 294, or 57.6%, of manuscripts. The next most common, the ostracon, appears 50 times, the codex a little less (45 times), followed by the rotulus (31), while the other formats – wall inscriptions, rolls, wooden and metal tablets, and bone – are all used for less than 10 manuscripts.

The patterns shift slightly if we compare the use of different formats among formularies (manuscripts containing recipes) versus applied texts (those amulets, curses etc. created in the course of rituals). Most formularies (102 of 188) are still written on sheets, and this likely represents the way in which recipes were used and circulated. they were probably normally copied onto small sheets which could be easily stored and consulted, which could be assembled into, and excerpted from, larger collections in more impressive formats. Interestingly, Ágnes Mihályko has observed similarly high proportions of sheets (35%) among liturgical manuscripts, and many medical texts are also preserved as individual sheets, implying that this format was very common for many genres of technical texts. The second and third most common formats for formularies are the codex (38 examples) and rotulus (26), with other formats only attested a handful of times each.

Among applied texts, the sheet still predominates (128 of196 manuscripts), but the second most common is the ostracon (26 examples). Again, these were likely chosen for functional reasons – the sheets and ostraca were generally small objects, which could easily be worn on the body (in the case of amulets) or buried in graves or at doorsteps (in the case of curses or love spells). While not well represented numerically, lead tablets and bones are important formats, since they only seem to have been used for curses.

When we sit down to write today we might choose to write on a scrap of paper, in a notebook, or on a computer. In just the same way, writers in Late Antique Egypt had many options when they decided to write a text, but their choice was never, or almost never, random. Rather, when someone decided to copy a magical text, their choice to use a particular format was shaped both by practical considerations relating to the text itself – whether they were copying a long collection of recipes, a short note, or an amulet – and by the materials and skills they possessed – whether they could more easily acquire papyrus, parchment or an ostracon, and whether they had the resources to acquire or the skills to produce a codex. In the next post in this series, we’ll look at another factor affecting the choice of format – the shift from one format to another over time.

References and Further Reading

Bagnall, Roger. Early Christian Books in Egypt. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2009.

Cromwell, Jennifer. “What is an Ostracon?” Papyrus Stories, 11 September 2019. https://papyrus-stories.com/2019/09/11/what-is-an-ostracon/

A helpful discussion of the history and use of the ostracon in Egypt.

den Heijer, Arco. “The Significance of the Book Connotations of the Codex as Christian Book Format in Second Century CE Egypt”. https://www.academia.edu/12349871/The_Significance_of_the_Book._Connotations_of_the_Codex_as_Christian_Book_Format_in_Second_Century_CE_Egypt

Harnett, Benjamin. “The Diffusion of the Codex”, Classical Antiquity 36.2 (2017): 183-235.

Hurtado, Larry W. The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins. Grand Rapids, Michigan: William B. Eerdmans, 2006.

Johnson, William A. Bookrolls and Scribes in Oxyrhynchus. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2004.

Martín Hernández, Raquel, and Torallas Tovar, Sofìa. “The Use of the Ostracon in Magical Practice in Late Antique Egypt.” Studi e Materiali di Storia delle Religioni 80 (2014): 780–800. URL

Roberts, Colin H. and T.C. Skeat. The Birth of the Codex. London: British Academy, 1983.

Mihálykó, Ágnes T. The Christian Liturgical Papyri: An Introduction. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2019.

Stroppa, Marco. “L’uso di rotuli per testi cristiani di carattere letterario”, Archiv für Papyrusforschung 59.2 (2013): 347-358.

Turner, Eric G. The Typology of the Early Codex. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1977.