In an earlier post in this series we talked about where the Coptic magical papyri come from – Egypt, and to a lesser extent, Sudan – but we noted that the majority of manuscripts had been purchased by foreign collections through the antiquities market. In this post we’ll look at where the Coptic magical manuscripts are now, and how they ended up there.

492 of the 508 Coptic-language magical manuscripts in our database have information on their present location. The country with the largest number is Germany, which has 140, followed by the United States, the United Kingdom, Austria, and France, which have more than 30 each. 28 are still in Egypt, while the remainder are spread between Sudan, where there are 4, and ten other countries.

If we look more closely at the 18 collections with more than 5 manuscripts each, we see some new patterns emerge. The largest collection belongs to the German Staatliche Museen, or State Museums, in Berlin, with 84 manuscripts. Next is the Vienna Nationalbibliothek (“National Library”), with 60. The American and British collections, though still large, are spread between several much smaller collections – the British Library and Museum, and the museums of Manchester, Cambridge, and Oxford in the UK, and the the universities of Michigan, Yale, Duke, and Pennsylvania in the US. The largest Egyptian collection is in the Coptic Museum, which has 9 Coptic-language magical manuscripts.

Although we’re looking specifically here at Coptic magical manuscripts, we should note that they are only one part of a much bigger story. The database Trismegistos contains a list of collections around the world containing papyrological manuscripts, and looking at the concentration of collections by country, we can see the same pattern – that the majority are in Western Europe and the United States.

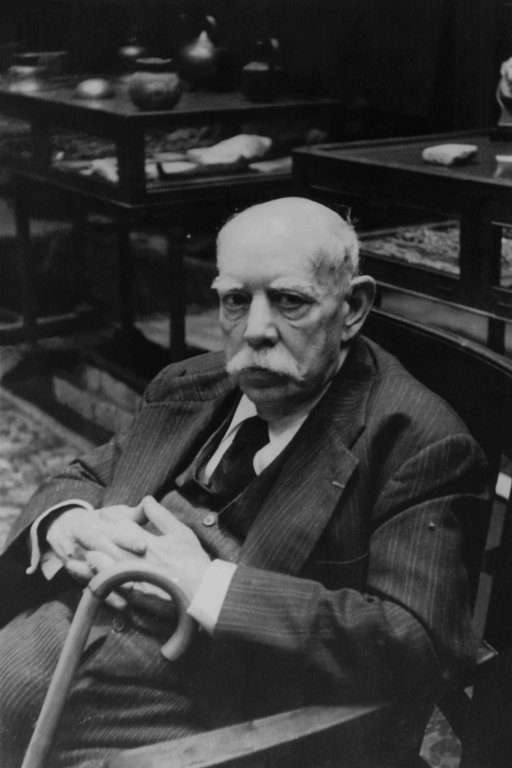

As the Egyptian papyrologist Usama Gad has observed, this is the result of a “complex legacy of imperialism and colonialism”. Already in the 18th century, Western European collectors had become interested in acquiring antiquities from Italy and Greece, and after Napoleon Bonaparte’s invasion of Egypt (1798-1801), acquiring the material remains of Egyptian history became a new way in which Western countries could compete with one another to demonstrate their political, cultural, and scientific power. While this sometimes took place through formal archaeological excavations run by foreign institutions and licensed by the Egyptian government, more often antiquities would be discovered by Egyptians, either accidentally, while looking for fertiliser, or in deliberate but unofficial excavations. These would then arrive in the hands of foreign collectors – usually European or American – through a series of middlemen; the most important of these was almost certainly Maurice Nahman (1868-1948), who ran his business from 1890 until his death in 1948, selling objects from all over Egypt from his store in Cairo. Our database notes that 28 Coptic-language magical manuscripts passed through Nahman’s hands, and given the incompleteness of most institutional records, the true number is likely much higher.

The earliest acquisitions of Coptic magical manuscripts were almost accidental; institutions purchased them in lots containing hundreds or thousands of objects from Egypt, including papyri in other languages (Egyptian hieroglyphs or hieratic, Demotic, Greek), and other artefacts, such as statues or jewellery. The beautifully-preserved AMS 9, for example, was purchased by the Museum of Antiquities in Leiden in an 1828 sale by Jean d’Anastasy, the Greek consul of Sweden and Norway, which included nearly 6,000 objects, of which only 147 were papyri.

Even when papyri became more of a priority for collectors, Coptic magical texts were not usually the focus; Vienna’s large collection is due to the purchase of over 100,000 papyri by the Archduke Rainer Ferdinand of Austria (1827-1913) from 1883/4 to 1889 – the 60 Coptic magical manuscripts are a tiny part of this. Nonetheless, an increasing demand for papyri led to the creation of “cartels” – groups of institutions who jointly purchased papyri from dealers in Egypt before dividing them between collections. The German Papyruskartell (1902-1914) is responsible for the many of the papyri in German collections, as well as for that in Strasbourg, which was part of Germany from 1871-1918. A similar British-American cartel, active from roughly 1920 to the mid-1930s, is responsible for many of the papyri held by the British Museum, Michigan, Columbia, and Yale. While this was a convenient way for early papyrologists to acquire material, it has created considerable problems in the long run; there is usually no record of how or where the papyri had been found, or how the papyri had left Egypt, and the division of manuscripts between collections means that collections, and even different fragments of single papyri, were split up.

There are some exceptions to the general trend of Coptic magical manuscripts being acquired almost unintentionally. In 1895, Dr. Reinhardt purchased 20 Coptic magical (and one alchemical) papyri, and a few fragments, from an unknown dealer in the Fayum – these were probably a single archive, which had been found together. A similar case is the purchase of an archive of 9 codices and sheets by Carl Schmidt in 1930, probably from Maurice Nahman, for the Heidelberg collection. While both of these represent cases where groups of manuscripts were kept together, rather than being dispersed, the circumstances of their discovery and removal from Egypt are still very poorly documented, and so much useful information has been lost.

As we’ve discussed before, the ideal case for the discovery of manuscripts is controlled and carefully recorded excavations, as in Kellis and Naqlun, where we can even identify the people who used the texts, when they lived, and can reconstruct other details of their lives. Artefacts found in excavations of this type are usually kept in storehouses near the site, and this is the case for at least 9 manuscripts in our database, while a further 4, most wall-paintings or inscriptions, are still in situ – in their original locations.

The steady stream of historical artefacts, including papyri, out of their country was already a matter of concern for Egyptians in the nineteenth century, and Egypt was one of the first countries to put in place legal controls on the export of antiquities, with laws passed in 1835, 1874, and 1912. In 1951 the Egyptian government passed a new law to protect cultural heritage, which essentially brought an end to the legal antiquities trade, and although this slowed the removal of papyri from Egypt, it did not stop it. It did, however, mark a new international understanding, reflected in a 1970 UNESCO convention, which entered into force in 1972 before being adopted by individual countries over the next decade or so. In theory this meant that any purchase of an Egyptian artefact, including papyrus, had to be accompanied by evidence that it had been acquired legally, which is usually taken to mean that it left Egypt before 1972. In reality, many collections, and even private individuals, continued to buy papyri, often without keeping meaningful records of their provenance. Papyrologists, who sometimes played a role in the acquisition of papyri, were in general very slow to accommodate themselves to the new realities. It was only in 2007 that the American Society of Papyrologists passed a resolution addressing the problem of the illegal papyrus trade, requiring that publications of papyri provide a “frank and thorough discussion of the provenance of every item”. Nonetheless, papyrologists such as Usama Gad, Roberta Mazza, and Brent Nongbri, to mention a few, have recently written extensively on these issues over the last decade, and papyrologists are increasingly aware of the way in which their work interacts with the papyrus trade.

The last few years have seen an increased public awareness of the ethical stakes of apparently neutral institutions such as museums, and there are increasingly public calls for the return of culturally important objects held outside their countries of origin, such as the Parthenon Marbles, the Benin Bronzes, and the Rosetta Stone. In the world of papyrology, the ongoing revelations of the purchase of stolen material by the Museum of the Bible in Washington D.C. have highlighted serious problems in the way collections are acquired and managed. Coptic-language magical manuscripts lack the cultural and ideological stature of marble friezes or early copies of the Bible, but they are nonetheless one part of this picture, which is in turn part of the larger problem of the structural inequalities between countries and individuals caused by the legacies of colonialism and imperialism.

Bibliography and Further Reading

Al-Azm, Amr & Katie A. Paul. “How Facebook Made It Easier Than Ever to Traffic Middle Eastern Antiquities”. World Politics Review. 14 August 2018. [URL]

Bierbrier, Morris L. “Art and Antiquities for Government’s Sake.” In Views of Ancient Egypt since Napoleon Bonaparte: Imperialism, Colonialism, and Modern Appropriations, edited by David Jeffreys (London: UCL Press, 2003), 69-75.

Blouin, Katherine, Usama A. Gad, and Rachel Mairs. Everyday Orientalism (blog) [URL]

Choat, Malcolm. “Provenance and the papyri”. Markers of Authenticity. 25 April 2016. [URL]

Gad, Usama A. “Decolonizing the Troubled Archive of Egyptian Papyri.” Everyday Orientalism. 5 August 2019. [URL]

Gad, Usama A. “Papyrology and Eurocentrism, Partners in Crime.” In Eidolon. 8 November 2019 [URL]

Gardner, Iain and Jay Johnston. “‘I, Deacon Iohannes, Servant Of Michael’: A New Look at P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 682 and a Possible Context for the Heidelberg Magical Archive.” Journal of Coptic Studies 21 (2019) 31-32. [URL]

Gonis, Nikolaos. “Mommsen, Grenfell, and ‘the Century of Papyrology’.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 156 (2006): 195-196.

González-Ruibal, Alfredo. “Colonialism and European Archaeology.” In Handbook of Postcolonial Archaeology, edited by Jane Lydon and Uzma Rizvi (Walnut Creek: Left Coast Press, 2010), 39-50. [URL]

Hagen, Fredrik & Kim Ryholt. The Antiquities Trade in Egypt 1880-1930: The H.O. Lange Papers. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Danske Videnskabernes Selskab, 2016.

Keenan, James G. “The History of the Discipline.” In The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology, edited by Roger S. Bagnall (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 37-47.

Mazza, Roberta. “The Illegal Papyrus Trade and What Scholars Can Do to Stop It”. Hyperallergic. 1 March 2018. [URL]

Verhoogt, Arthur. The University of Michigan Papyrus Collection (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2017).