In the past posts in this series, we’ve looked at individual manuscripts – how to classify them, where and when they come from, what they were made from, and the forms that they took. But individual manuscripts are only part of the story, so this week we’ll introduce the concept of archives, groups of manuscripts which give us more information than individual manuscripts would on their own.

In papyrology an “archive” is a group of documents which were brought together by a historical individual for a specific purpose. Sometimes these are libraries – books which someone might have collected and purchased because they wanted to read them; sometimes they are official archives – collections of census records and other official documents; sometimes they are mixed private collections consisting of receipts, letters, notes, poems, and so on, collected by an individual over the course of their lives. The online papyrological database, Trismegistos, contains records of 537 archives from the ancient world, dating from the 8th century BCE to the 8th century CE.

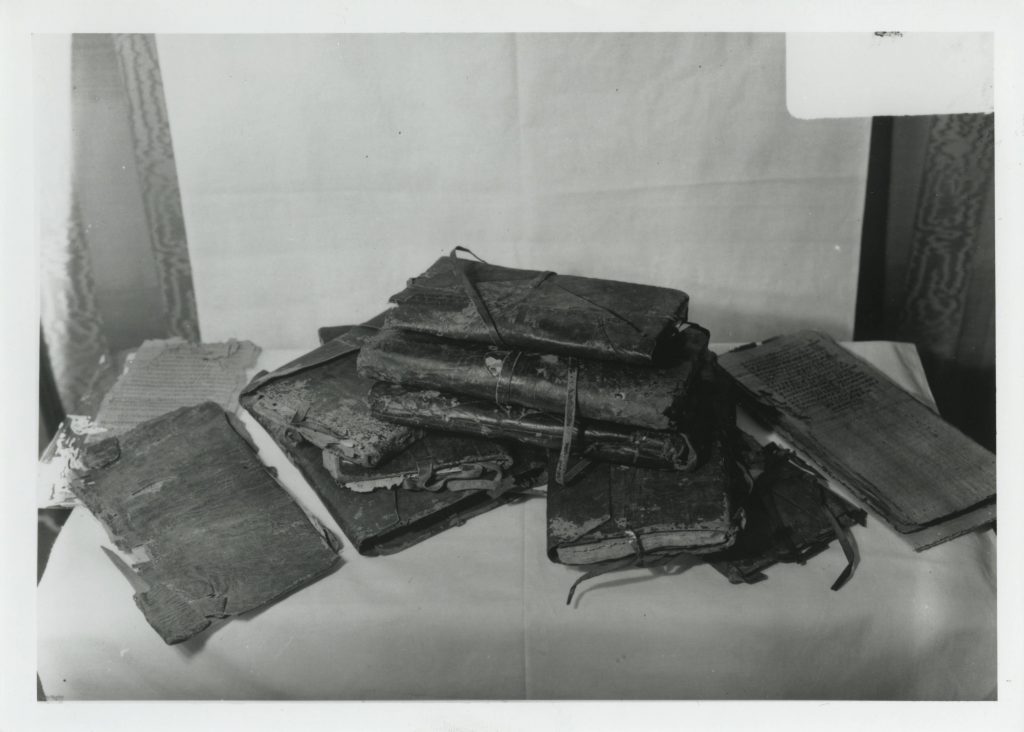

Usually, scholars can identify manuscripts as belonging to an archive because they are found together – we might find a jar or chest containing a group of documents, or find papyri scattered in an abandoned house. Most papyri, however, have been discovered through informal and/or illicit excavations, and so archives must be carefully reconstructed by scholars through “museum archaeology” – the process of studying documents relating to the sale and acquisition of the manuscripts, in order to piece together a picture of their discovery.

There are some very famous archives – the Nag Hammadi Library is a group of twelve codices believed to have been found in a jar in a tomb-cave near the city of Nag Hammadi. This archive is famous for the many “Gnostic” texts it contains, attesting to alternative forms of Christianity which existed alongside what we now think of as the Catholic or Orthodox variety. While archives containing magical manuscripts are less well-known, we have so far reconstructed 52 likely archives which contain at least one “magical” text.

We have already discussed some of these; over 200 texts were found in a house from fourth-century Kellis, among them a letter containing instructions for a spell to separate a couple, a handbook for creating amulets, and an example of an amulet created for a man called Pamour. A century later, the collection of texts found in the hermitage of the monk Phoibammon in Naqlun includes another separation spell, as well as a curse, and instructions for magically reconciling a quarreling couple, and healing migraines and fever. These groups of texts, with known findspots, and other non-magical texts, allow us to reconstruct, to some extent, the lives of the people who created and used them more fully than we could if we only had a single surviving manuscript.

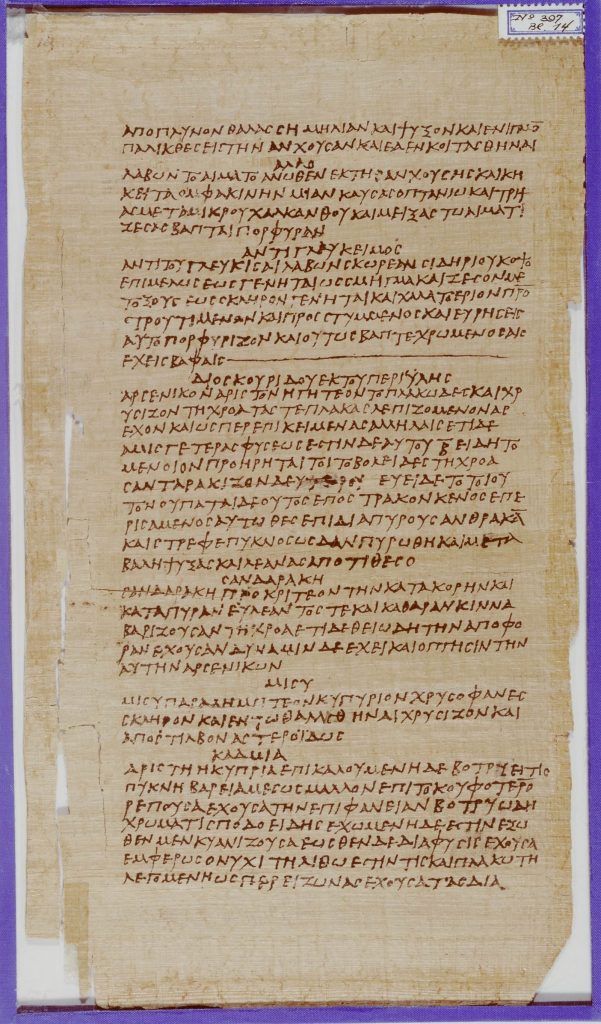

The best known magical archive, however, is the so-called “Theban Magical Library”. This archive, dating from the second, third, and fourth centuries CE, contains ten papyri, eight magical, and two alchemical. These include the longest surviving magical texts, and some of the earliest surviving evidence for ancient alchemy. Although these contain some of the Old Coptic texts that we have discussed in past posts, most of their texts are written in the older form of the Egyptian language known as Demotic, and Greek, the principal written language of Roman Egypt.

| Papyrus | Languages | Date | Contents | Format |

| PDM/ PGM XII | Greek, Demotic | 2nd-3rd cent. CE | Myth of the Sun’s Eye; Magical and alchemical | Roll |

| PDM/ PGM XIV | Demotic, Greek | 2nd-3rd cent. CE | Magical | Roll |

| PDM Suppl. | Demotic, Greek | 2nd-3rd cent. CE | Magical | Roll |

| PGM I | Greek, Old Coptic | 3rd cent. CE | Magical | Roll |

| PGM II+ VI | Greek | 3rd cent. CE | Magical | Roll |

| PGM IV | Greek, Old Coptic | 4th cent. CE | Magical | Codex |

| PGM V | Greek | 4th cent. CE | Magical | Codex |

| P.Holm + PGM Va | Greek | 4th cent. CE | Alchemical and magical | Codex |

| PGM XIII | Greek | 4th cent. CE | Magical | Codex |

| P.Leid. I 397 | Greek | 4th cent. CE | Alchemical | Codex |

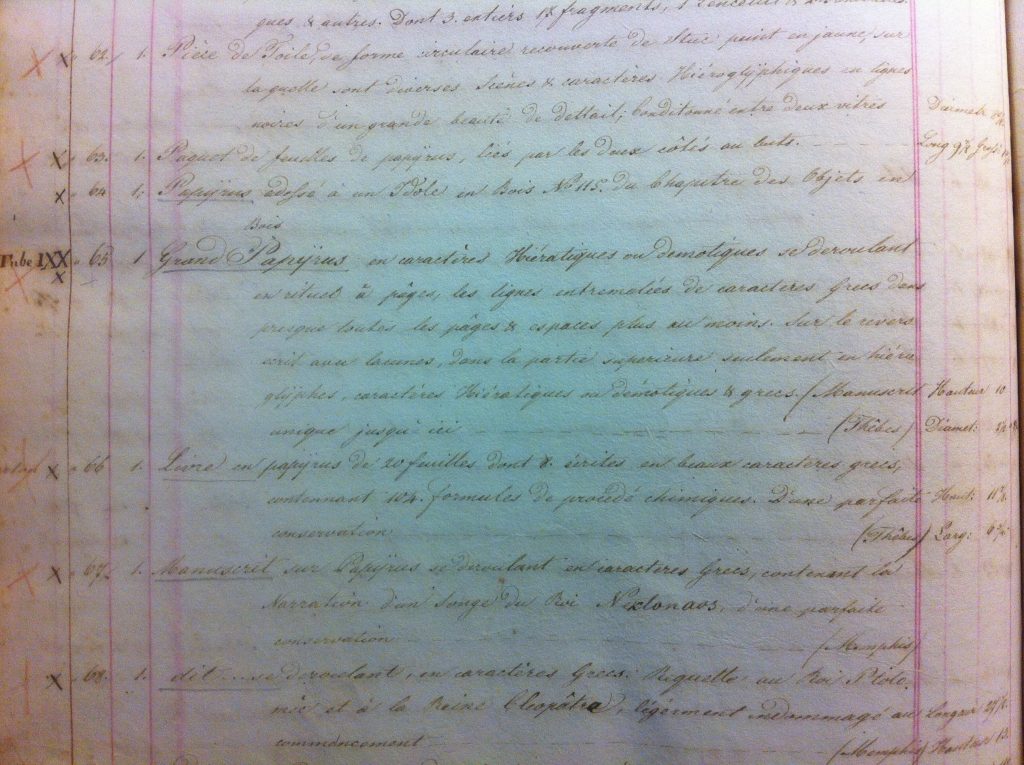

We know relatively little about where this group of texts originally came from; they seem to have been found by a group of native Egyptians in Upper Egypt at some point in the early 19th century. The manuscripts were then sold to Jean d’Anastasy, a Greek merchant whose role as a middle-man in the lucrative trade of Egyptian grain for Swedish iron led to him becoming one of the most prominent men in Alexandria, a knight of the Swedish Order of Vasa, and the consul for Sweden and Norway in Egypt from 1828-1857. Anastasy was a prolific collector of antiquities, both those his agents excavated around the country, and those which they bought from native Egyptians, and by 1828, when he began to sell it to European collections, it was said to be the third largest in the world. Between 1828 and 1856, he sold and donated over 8,000 papyri, coffins, statues, and other artefacts to collections in the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, France, and Sweden.

Although they represented only a tiny part of his original collection, his magical papyri attracted the attention of scholars very early on, and in 1830, Caspar Reuvens, the director of the Museum of Antiquities in Leiden, the Netherlands, suggested that several of the magical papyri that they had bought from Anastasy belonged to a single archive. He came to this conclusion based on several pieces of information – the fact that Anastasy’s catalogue noted that they had all been acquired in the same place (Thebes), that several of them seemed to have been written by the same group of scribes, and that their contents were noticeably similar. There is no clear evidence that Anastasy ever confirmed that the papyri belonged together – and he may never have known much about these manuscripts, given the size of his collection – but the work of scholars since then seems to confirm that the ten papyri do form some sort of archive.

In contrast to the Kellis and Naqlun archives, the Theban Magical Library lacks a clear context of discovery, and accompanying non-magical texts, like letters, which might tell us more about the people who used it, but we can still use the texts together to piece together a picture of its history. The oldest text in the Library, for example, is not magical, but a Demotic literary text, the Myth of the Sun’s Eye, a story which tells how the goddess Tefnut, the Eye of the Sun, became angry and left Egypt, and had to be persuaded to return by the god Thoth. In the Roman period, it would be very unlikely that a text of this type would be found anywhere except in a temple library, which implies that the earliest users of the Theban Magical Library may have been Egyptian priests. This idea is confirmed when we see that three of the earliest magical rolls, from the second or early third century CE, are written in Demotic, knowledge of which was restricted to priests in the Roman period, as far as we are able to tell.

At the same time, some other third-century texts are written in Greek, as are almost all of the fourth-century texts; this suggests to us that the Library was probably handed down or inherited from someone trained as an Egyptian priest, to someone for whom Greek was their main written language. Indeed, one of the earlier rolls (PDM xii) has been repaired in such a way that some of its Demotic texts are hidden, but the Greek texts which are written alongside it remain visible; this implies that the person who was using the texts in the fourth-century was not able to read Demotic. At the same time, the Old Coptic texts in one of the fourth-century texts contain implies that the user was still able to understand the Egyptian language, and so was likely still an ethnic Egyptian.

From the contents of the texts, it seems that the users of the Theban Magical Library were interested in “magical” rituals – curses, love and healing spells, and in particular divination – but also in alchemy, something which is not paralleled in any other contemporary magical texts. While we tend to imagine “alchemy” as a kind of mystical practice involving the transformation of lead into gold, at this time it referred to a basic form of chemistry, mainly focused on producing semi-precious stones, alloys of metal, dyes for fabrics, and metallic inks. The two large alchemical codices are in almost perfect condition, leading some scholars to suggest that they were read by someone interested in alchemy, but never practiced – although it’s also possible that the Library’s owners were just very careful with their books! The recipes seem to focus on producing metal statues and luxury manuscripts, as well as purple fabrics without using the expensive dye made from the shellfish known as the murex. These suggest that alongside being “magicians”, the fourth-century users of the Library may have been craftsmen.

There are many more details that scholars have managed to reconstruct based on the rich manuscripts of the Theban Magical Library, but the examples given here show that even the basic details of language and content allow us to suggest something of its history; originally the property of someone trained in an Egyptian temple, the Library was inherited and enlarged by an Egyptian literate in Greek but not Demotic, whose interests included not only magic, but the production of luxury objects. The archive as a whole tells us a larger story than any one of its individual manuscripts. As our project continues, we hope that we can use the study of archives, alongside other contextual information, to help reconstruct the role of magical texts in the lives of people from Roman and early Islamic Egypt.

Bibliography

Brashear, William M. “The Greek Magical Papyri: An Introduction and Survey; Annotated Bibliography (1928-1994).” In Aufstieg und Niedergang der römischen Welt 2.18.5, edited by Wolfgang Haase (Berlin: Walter de Gruyter & Co., 1995): 3380-3684.

de Haro Sanchez, Magali. “Les Papyrus Iatromagiques Grecs de Kellis”, Lucida Intervalla 37 (2008): 79-98. URL

de Haro Sanchez, Magali. “Les papyrus iatromagiques grecs et la région thébaine.” In «Et maintenant ce ne sont plus que des villages … » Thèbes et sa région aux époques hellénistique, romaine et byzantine: Actes du colloque tenu à Bruxelles les 2 Et 3 Décembre 2005, edited by Alain Delattre and Paul Heilporn (Brussels: Association Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth, 2008), 97-102. URL

Dieleman, Jacco. Priests, Tongues, and Rites: the London-Leiden Magical Manuscripts and Translation in Egyptian Ritual (100-300 CE), Brill, 2005.

Dosoo, Korshi. “A History of the Theban Magical Library”. Bulletin of the American Society of Papyrologists 53 (2016), 251-274. URL

Fournet, Jean-Luc. “Archives and Libraries in Greco-Roman Egypt”, in A. Bausi, C. Brockmann, M. Friedrich, S. Kienitz (eds.), Manuscripts and Archives: Comparative Views on Record-Keeping, Berlin: De Gruyter 2018, 171-199. URL

Gardner, Iain and Jay Johnston. “‘I, Deacon Iohannes, Servant Of Michael’: A New Look at P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 682 and a Possible Context for the Heidelberg Magical Archive”. Journal of Coptic Studies 21 (2019): 51-53. URL

Tait, W.J. “Theban magic.” In Hundred-Gated Thebes: Acts of a Colloquium on Thebes and the Theban Area in the Graeco-Roman Period (P. L. Bat. 27), edited by S P Vleeming (Leiden: Brill, 1995), 169-182.

Vandorpe, Katelijn. “Archives and Dossiers.” In The Oxford Handbook of Papyrology, edited by Roger S. Bagnall (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007), 216-255. URL

Verhoogt, Arthur. “Papyri in the Archaeological Record.” In The Oxford Handbook of Roman Egypt, edited by Christina Riggs (Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2012), 507-515. URL

Zago, Michela. Tebe Magica e Alchemica: L’idea di biblioteca nell’Egitto romano: la Collezione Anastasi, Padova, libreriauniversitaria.it edizioni, 2010.