Photo (C) RMN-Grand Palais (musée du Louvre) / image RMN-GP

Now that most of our corpus has been entered into our database, we can begin to visualise it in various interesting ways. In the next few posts of this series we’ll examine some of the statistical features of the manuscripts containing Coptic magical texts, beginning with their distribution over time.

In our project description, we say that the texts which we study date to between the third and twelfth centuries CE. This coincides with the period that Coptic was used as a written form of the Egyptian language; the earliest texts in standard Coptic probably date to the third century. By the twelfth century it had largely been replaced by Arabic, even among Christians, although it remained in use as a liturgical language in the Coptic Orthodox Church, and some Egyptian Christians continued to study Coptic and, more rarely, to compose new texts in it.

Of the 502 magical manuscripts containing Coptic in our database, 499 have dates associated with them – the remaining three are unpublished, and so have no published dates. In our database, there are actually 4 dates associated with each entry – an earliest and latest date for composition and for copying. Usually the composition field is empty, since we have no idea when the texts we study were composed; they are almost always copies of older texts. Typically, papyrological manuscripts are dated by century, and so a text dated by its editor to the fifth century would have 401 as the earliest date of its copy, and 500 as its latest. Although there are no Coptic texts written before the common era, texts in other languages in our database have BCE dates indicated with a minus sign (-) at the beginning.

If we graph the dates of the manuscripts in our database, the following pattern emerges:

The earliest texts do indeed date to the third century, while the majority date between the 6th and 8th centuries, with a second peak in the 10th and 11th centuries. Although the 12th century marks the last century with significant numbers of texts, there are a few which appear as late as the 15th.

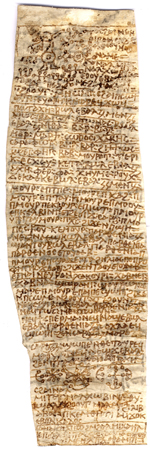

These facts deserve a few comments. First of all, magical texts very rarely have specific dates – this is why they are dated to a period of a century or more. There are a few rare exceptions to this – the clearest are where a scribe has written a colophon, a short text giving his name, the date the text was written, and sometimes a request that the reader prays for him. We only have two of these in the Coptic magical corpus, and the best known is from P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 682, a formulary containing two curses, copied by the Deacon Iohannes on the 9th October 967 CE. This sheet is actually part of a large collection of 11 manuscripts which all belong together, several copied by Iohannes, known as the Heidelberg Magical Library, since its texts are owned by the University of Heidelberg. This library, dating to the 10th and 11th century, is largely responsible for the bump in the number of texts from these centuries. A more careful future statistical analysis, once we have finished grouping texts, would count individual finds, rather than manuscripts, and so reduce the Heidelberg Library to a single datapoint. This would probably lead to a more straightforward bell-curve.

Although the earliest texts date to the third century, and the latest to the 15th century, we should take these numbers with a small grain of salt; Coptic handwriting, which we have to rely on in the absence of colophons, is very difficult to date. This is largely because it has been studied for a shorter time, and by far fewer scholars, than Greek handwriting, and there are fewer dated Coptic manuscripts which help us establish what the writing of different periods looks like. For this reason, it’s not uncommon for manuscripts to be dated to periods of two, three, or even four hundred years. Some scholars may be very cautious, and suggest no date for their manuscript; if this happens, we will tend to date it to between 301 to 1200 CE, the entire period that Coptic magical texts were widely used, to avoid having such an important field empty. This means that the data used in this first graph is often quite fuzzy; as our project progresses, one of our key goals is to narrow down the dating of manuscripts by carefully comparing the hands which wrote magical texts to each other, and to dated non-magical texts, but for now we must rely largely on published information.

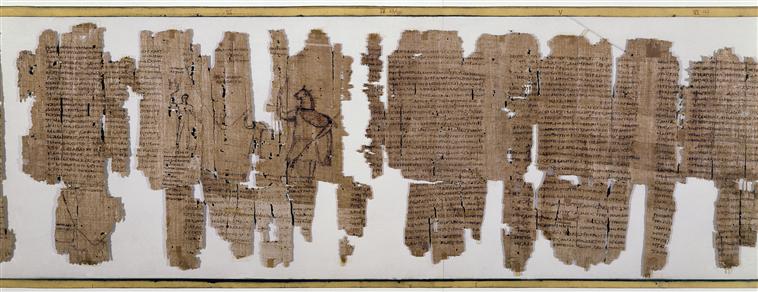

In reality, only two manuscripts can be fairly reliably dated to the third century CE, the two rolls which make up PGM III, written mainly in Greek, but with three rituals, one for summoning the sun god to appear, written in Old Coptic. This “Old Coptic” is a non-standard form of Coptic, used mainly by the priests of the traditional Egyptian gods in the early centuries CE.

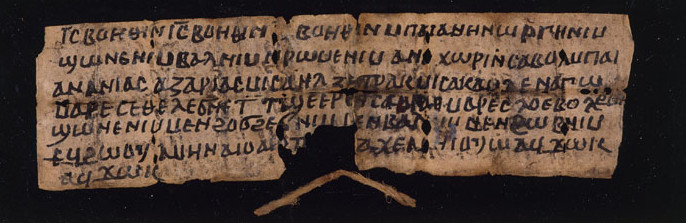

The latest Coptic magical texts, dated to between 1101 and 1500 CE, are a series of inscriptions from a cathedral in Faras in Nubia; since they contain only the names of the Four Living Creatures from Revelation, they could be considered either Greek or Coptic, and they could date to almost any year in which the cathedral was used.

From these comments, you should be able to see that the data shown in the first graph probably contains many problems, and so it’s useful to look at a smaller set of data, the 132 manuscripts dated by their editors to a single century.

Although there are far fewer of these, it’s interesting to note that they broadly follow the same pattern as we see in the earlier graph. Again, the greatest concentration occurs around the seventh century, the period after the Arab conquest when Coptic had largely displaced Greek as the language of administration and correspondence, but had not yet been replaced by Arabic. Again there is a spike in the 10th and 11th centuries – even more noticeable this time, since the Heidelberg Library contains some of the best dated texts. We can see though that none of the reliably dated manuscripts are later than the twelfth century, which is what we would expect. There are actually only three manuscripts dated to this last 100 years – one of them is an amulet asking for protection for a woman named Sethelecnet, written on a piece of paper previously used to write a text in Arabic.

Image © 2004 Musée du Louvre / Georges Poncet

This kind of data is interesting for scholars who want to understand the rise and development of Coptic, but behind these numbers we can also see a story about the Coptic language and the people who spoke it. The earliest texts (PGM III.1 & 2), are non-Christian, and show part of the history of the development of a new way of writing Egyptian, which was accessible to people who spoke Egyptian, and could write in Greek, but didn’t have the skills to write the more complex Demotic script learned in temples. Until Coptic became a widely-used written language, an Egyptian-speaker who wanted to write a letter but could not write Demotic would need to rely on someone literate in Greek to translate and write their message, and the recipient would need another Greek speaker to translate it back for them. The explosion of Coptic’s popularity as a language for magic after the fifth century is probably linked to the fact that the Egyptian-speaking majority suddenly had an accessible way to write their language, as well as to its association with Christianity and monasticism – both of which became major forces in Egypt in this time. This close association between Coptic as a written language and its speakers explains the likely disappearance of Coptic magical texts in the twelfth-century; by this time most Christians had converted to Islam, and even those who hadn’t tended to use Arabic as their everyday language. Although Egyptians – Christians, Jews and Muslims – continued to practice magic, they increasingly did so in Arabic.

References and Further Reading

Betz, Hans D. The Greek Magical Papyri in Translation. Including the Demotic Spells. Vol. 1. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986, 18-36, no. III. URL

Translation of PGM III, including the earliest Coptic magical texts.

Bosson, Nathalie. “Amulette-palimpseste magique du musée du Louvre”. Orientalia, NOVA SERIES 67, no. 1 (1998): pp. 107-114. URL

Edition and French translation of P. Louvre inv. E 32317, one of the latest Coptic magical texts.

Gardner, Iain and Jay Johnston. “‘I, Deacon Iohannes, Servant Of Michael’: A New Look at P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 682 and a Possible Context for the Heidelberg Magical Archive”. Journal of Coptic Studies 21 (2019) 51-53.

URL

A very rich article, containing, among other things, a discussion of P. Heid. Inv. Kopt. 682 and its colophon.

Love, Edward O. D. “The PGM III Archive.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 202 (2017), p. 175-188. URL

This article discusses PGM III, and argues that it is in fact two separate rolls – this is why we refer to it in this article as PGM III.1 & 2

Michalowski, Kazimierz. Faras II, Fouilles Polonaises 1961-1962. Warsaw : Pánstwowe Wydawaictwo naukowe, 1962, 192-193, nos. 71-73.

This volume contains the three inscriptions from the cathedral of Faras which we class as the latest possible “Coptic magical texts”.

Preisendanz, Karl, and Albert Henrichs. Papyri Graecae Magicae: Die Griechischen Zauberpapyri. 2 Vols. Stuttgart: Teubner, 1973–1974, vol. 1, 30-63, no. III.

Edition and German translation of PGM III, including the earliest Coptic magical texts.

One Comment

Pingback: